Medieval to modernist: Palestinian artist inspired by Jerusalem's melting pot

In 1996 Palestinian artist Kamal Boullata, who died last year aged 77, created 12 abstract screen prints as part of his "Granada portfolio", an artistic response to the famed Alhambra palace and its reflecting pools. Interlaced geometric shapes, they create diamonds of colour that conjure the impression of shimmering reflections on water.

These are now hanging on the wall of the West Court Gallery at Jesus College, Cambridge, UK, as part of "Jerusalem in Exile", an exhibition of Boullata's work, which is running until the 13th March.

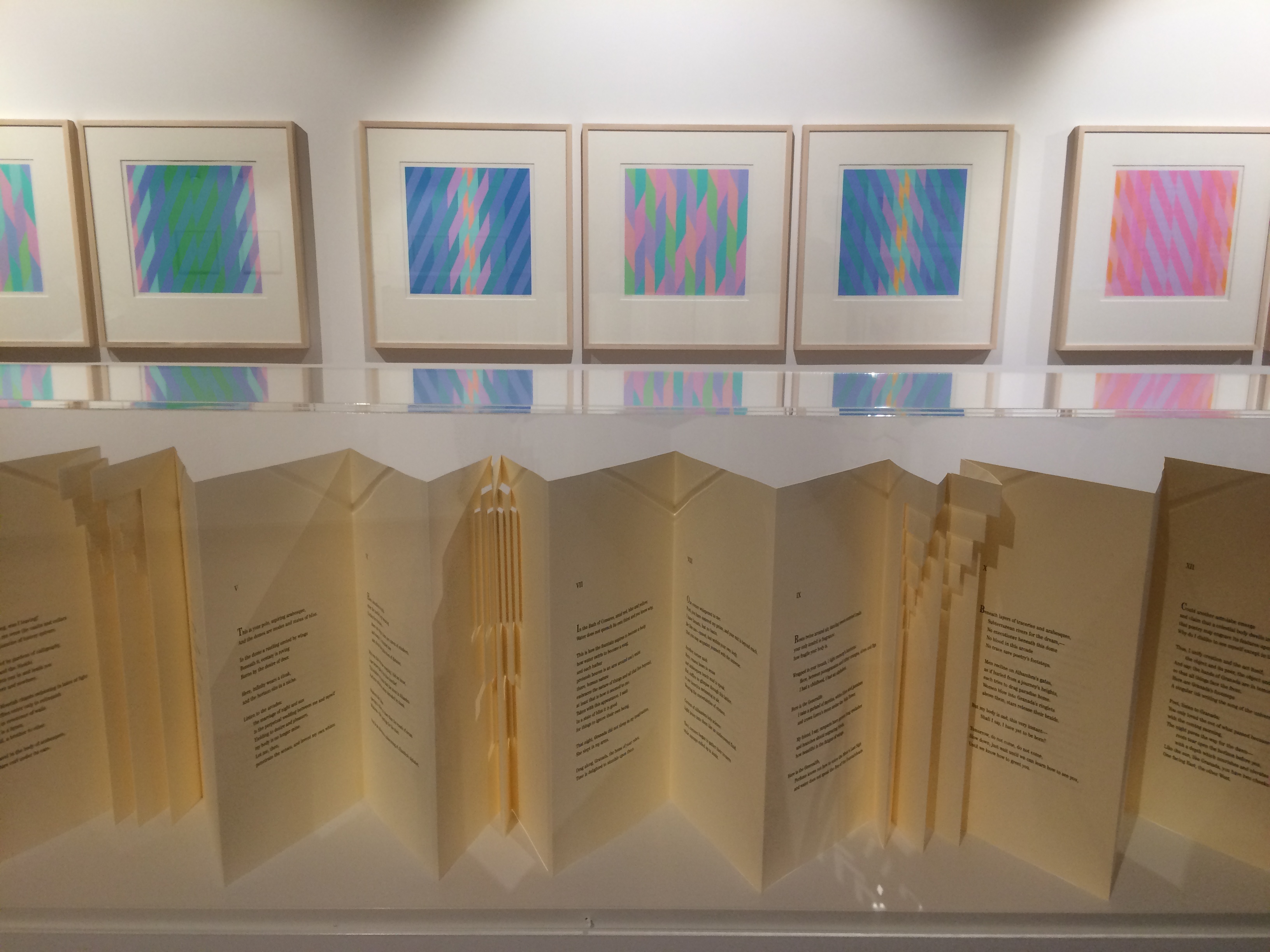

A “beautiful accident” happened in the making of this tiny jewel of a show, says cultural historian and senior researcher at Cambridge University, Elizabeth Key Fowden. The screen prints are themselves reflected across a display case holding the second part of the “Granada Portfolio”: a concertinaed book of the Syrian poet Adonis’ verses, Twelve Lanterns for Granada.

Reflections, in reflections: a kaleidoscopic effect that would have made Boullata proud.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

'Jerusalem in Exile'

The West Court Gallery is a modest space, in one room that partly serves as a walk-through between two areas of the college. The works reward both fleeting glimpse, and close-up scrutiny of colour and line.

The "Granada Portfolio" includes the four sets of three silk screens named after the "four rivers believed to flow into Paradise", spelled here as Bisan, Dijlat, Jaihun, Furat. They have a flickering quality, a lattice of blues, greens, reds and oranges, a geometric abstract of glancing light on water.

Meanwhile the accordion pages of Adonis’ Twelve Lanterns for the Alhambra, created in 1994, are cut to make architectural forms reminiscent of the muqarnas, the ornamental vaulting niches at the Moorish palace.

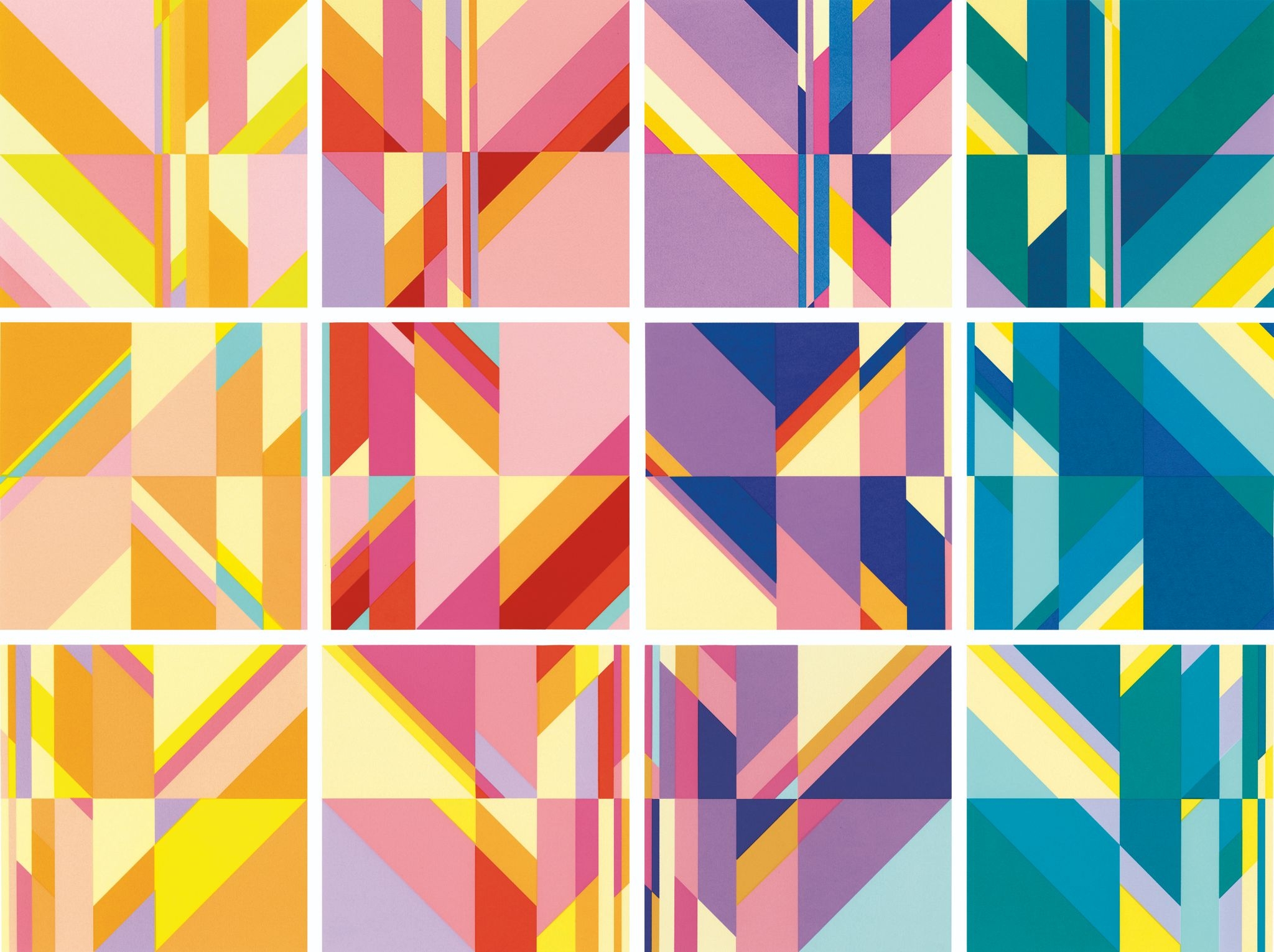

Across the room are a second set of colour screen prints also dating from the mid-1990s - Three Quartets, equally eye-catching, in abstracts more challenging and modernistic. This work evolved from the idea of dividing the square vertically and diagonally, in a ratio “originally proposed” by the ninth century Arab mathematician Thabit Ibn Qurra.

Engaging further with the show takes you to Sizain, 2002, a set of “blind embossed” prints on a third wall - colourless, using raised shapes of the paper.

They delve deeper into what Fowden, in the handsome limited-edition hand-bound catalogue, itself an “artist’s book”, calls Boullata’s life-long fascination with the infinite potential of the square”. The white-on-white patterns across interlocking squares sit somewhere between an obsessively refined doodle and a quest for the infinite.

An artist in exile

Boullata died in Berlin last August after a life lived in forced exile since the Israeli occupation of East Jerusalem, the city of his birth, in the 1967 war.

In Beirut at the time exhibiting his work, Boullata was denied the right to return and spent the next 50 years living between the United States, Morocco and France, before moving to Berlin in 2012.

Boullata was always described as a leading Palestinian artist, and a pioneer of researching and writing about Palestinian art.

His book Palestinian Art: From 1850 to the Present, was a fierce assertion of a Palestinian art history, with a strongly supportive preface by his friend, the pre-eminent English art critic, John Berger.

He was also part of the hurufiyya movement, bringing Arabic calligraphy and Modernism together, and spoke often of being inspired by the light and architecture of Jerusalem.

Collaborative works

Throughout his life Boullata exhibited internationally, with more than 20 solo shows from Amman and Dubai to Paris, London and Washington; works are held by the Barjeel Art Foundation, the Dalloul Arab Art Foundation and the Patronato de la Alhambra Islamic Museum, among other collections.

His colourful geometric abstracts, often in screen prints and incorporating Arabic or Kufic script, are held in the British Museum and major regional collections.

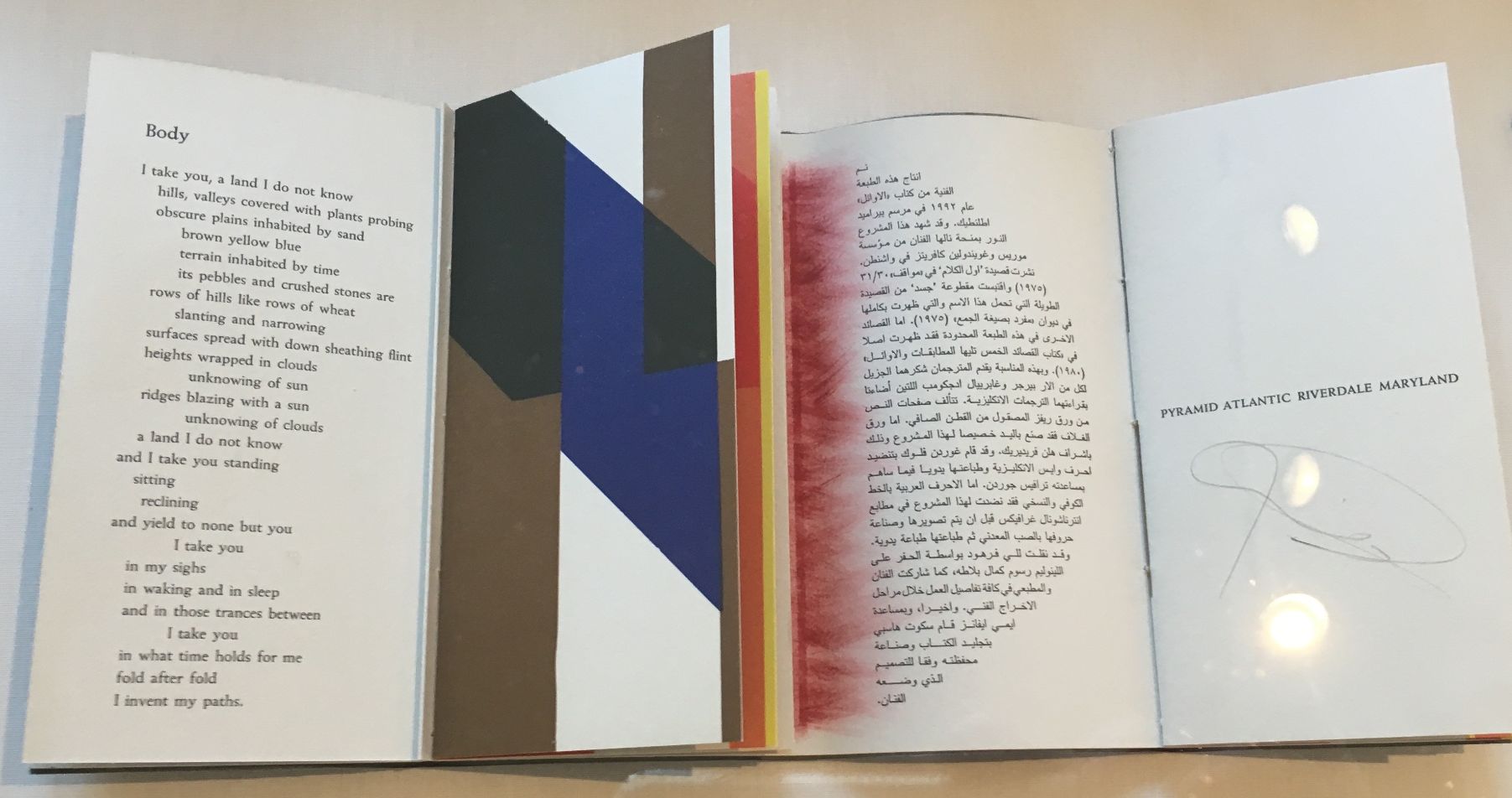

Boullata was working towards this exhibition, "Jerusalem in Exile", when he died. With the close support of his wife and long-time collaborator Lily Farhoud, who is co-curator, it has refocused on his “artist’s books”. These are works on paper that bring visual art and texts together, or a "combination of the visual and the verbal”, in Fowden’s words, in folding or book form.

Examples showcased here include collaborations with Adonis and the iconic Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, as well as leading French and Canadian poets.

Chant de la baleine bleue, for example, the "Song of the Blue Whale", is a kind of expanding fan of mottled watercolour, again relating to a text by Adonis. Another piece extending down a display case is Ode to the Land/The Night, of a 1976 poem by Darwish, in memory of the Palestinian protesters killed on the first Land Day in 1976.

Others engage with work by the Quebecoise poet and writer Denise Desautels, or France’s Bernard Noel. They comprise, in Boullata’s words, “the words’ meaning turned into a visual expression whereby the seeable and the sayable became interchangeable”.

Inspired by multiple faiths

The exhibition’s opening was marked by a symposium on meaning and abstraction in Arab and Islamic art that drew leading international scholars - and the publication of two major new books, Uninterrupted Fugue, on Boullata’s art, and There Where You Are Not, a collection of his writings.

'His insistence on the shared space of Jerusalem and creative opposition to monopolisation is clear'

- Elizabeth Key Fowden, Cultural historian

Boullata’s work was rooted in Arab geometry and script and inspired by Islamic archiecture from Jerusalem to Muslim Spain. But while many could easily take him as an Islamic artist, Boullata was a Palestinian Christian.

Soon after his death in Berlin, he was buried in the cemetery of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate in Jerusalem, the church in which he was raised and where many generations of his family were interred.

Fowden noted that Boullata had called himself “an existential Jew”. “He was raised Christian, he worked very much through the tradition of the icon, and more of his work is overtly Islamic in terms of its use of geometry and the spiritual inspiration behind it.”

"His insistence on the shared space of Jerusalem and creative opposition to monopolisation is clear in his use of Jewish, Christian and Muslim themes and figures as titles and themes of his art.”

The Dome of the Rock that was Boullata's boyhood inspiration, where he spent hours sketching the geometric shapes and mosaics, is itself a symbol of cross-cultural influences, a building that draws on Byzantine artistic and architectural traditions.

But he "refuses to be pigeonholed as a single identity,” said Fowden. “I think that’s very, very important for Arab art, for Islamic art, we are seeing increasingly that we are talking about universal accessibility not narrow identities, and he resisted that all his life.

“He’s not simply a Palestinian artist. He is Palestinian, he is a Jerusalemite. That’s how he would describe himself. His work was always universal.”

"Jerusalem in Exile" is on display at the West Court Gallery at Cambridge University's Jesus College until 13 March, co-curated by Claudia Tobin and Lily Farhoud.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.