Inspired By The East: Casting an eye over Orientalism

In 1978, Edward Said made Orientalism a dirty word in his book of the same name. The Palestinian writer and academic argued that patronising Western depictions of the East, and especially Arab culture, were bound up with imperialism, creating stereotypes of “the other”.

Said’s focus was on literature, but art historians followed his watershed volume with post-colonial rethinks of Orientalist art; typically 19th-century oil paintings by Western artists with romantic visions of the East, from the Hajj to the harem (the latter was an especial object of wild fantasy).

The main focus of Inspired By The East: How The Islamic World Influenced Western Art, which opens at the British Museum this week, is to revisit Orientalism in art and artefacts, a cultural exchange that goes far beyond the European and American male artists who delivered florid images of Turkey, Palestine and North Africa for Western audiences.

There’s no mention of Orientalism in the title: it is, after all, still “a highly charged and contested term” as one caption as the exhibition notes

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Inspired By The East - the first Orientalism show in the UK since 2008 - casts its net further than art, referencing ceramics, architecture, photography, even theatre. It closes with responses from four of the biggest contemporary female artists of the region to the Orientalist cliche, including Iranian-American Shirin Neshat and Morocco's Laila Essaydi, both of who are well known for boldly confronting the stereotyped role of Muslim women in art.

Julia Tugwell, the exhibition's co-curator, explains: “It’s an East-West exchange and we want to talk about the influences of Islamic art, not just Islamic art but from the Islamic world, Islamic culture, on the West.

"This subject of Orientalism is generally thought of as 19th-century oil paintings, and what we want to do is show that it is wider than that.”

Two highlights capture this new approach. In late September, before the exhibition opened, Young Woman Reading (1880) by Osman Hamdi Bey, the French-trained Ottoman master, sold at Bonhams’ auctioneers for an astonishing £6.9m ($8.16m) - 10 times its pre-auction estimate of £700,000.

This luminous work is now on the wall at the British Museum, courtesy of the purchaser, the Islamic Art Museum (IAM) in Kuala Lumpur, funded by the Malaysian billionaire Syed Mokhtar Albukhary. Indeed the Albukhary family have lent 95 percent of the loans on display at Inspired By The East (the exhibition opens at the IAM after London).

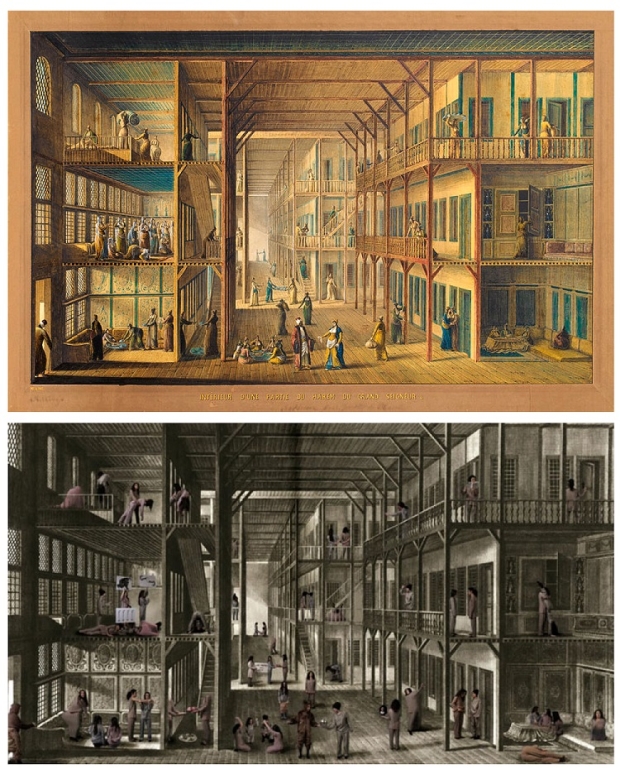

Then, around the corner from Young Woman Reading, is perhaps the outstanding piece in the show. Turkish artist Inci Eviner oversaw Turkey’s pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale: here she has taken Harem Of The Sultan, a classic Orientalist image by Antoine-Ignace Melling (1763-1831), a German artist who lived in Istanbul for 18 years, and turned it on its head.

Fantasy paintings of harems, with sensuous semi-naked women lounging around between trysts with their masters, were the best-selling staple of the Orientalist genre.

Instead Eviner’s Harem (2009), a flat-screen video piece, presents the women as if locked in a lunatic asylum. In shapeless, drab clothes, they flash their stomachs at the audience, put paper bags over their heads and bite arms in repetitive, strange movements. Some are shown strait-jacketed in ballooning outfits. (It’s an even greater irony given the relative sophistication with which Islamic medicine approached the care of the mentally ill during Melling's lifetime.)

Orientalism: The collectors

For all the post-modern, post-colonial criticism of Orientalist art, demand is driven by some of the Middle East’s biggest collectors.

At the Bonham’s auction in September, three works by the leading Austrian orientalist painter Ludwig Deutsch (1855-1935) also saw fierce bidding, selling for more than £2.6m ($3.2m).

The Qatar Museum Authority’s planned Orientalist Museum has yet to be built, but that has not stopped it from going on a massive buying spree to boost a collection now said to number almost 1,000 pieces.

Egyptian tycoon Shafik Gabr is another major collector, regarding Orientalist work as a bridge-builder rather than colonial kitsch. Sultan bin Muhammad Al-Qasimi, ruler of Sharjah, has another large collection.

“In the last 10 years or so there has been a huge interest in collections in the Islamic world being built, of Orientalist paintings,” says Tugwell. “They are being collected in the Middle East and who knows what the reasons are.

“Some people say it’s a way of taking back their past when they didn’t have their own painters in the 19th century painting in the way the Europeans were, as a documentarians.

“In a sense that’s correct, [but] in a sense that’s false because a lot of these paintings are romanticised. But they are now taking an interest in a Europeanised representation of their own culture.”

But if the works displayed in Inspired By The East are anything to go by, then the Albukhary have come late to Orientalist collecting - and paid a price.

The paintings that fill one long wall in the show are thin on great works by the big British masters. Yes, there is A Memlook Bey (1868) by John Frederick Lewis, who lived in Cairo from 1841-51, is a glowing self-portrait of the artist in turban and scimitar, if modest in scale.

But the small pieces by Edward Lear, the exquisite painter and nonsense poet, and David Roberts, the former scene painter turned panoramic painter, are underwhelming.

That said, Edwin Lord Weeks’ painting of Rabat’s Red Gate (1879) is rich and vivid. Otto Pilny’s Evening Prayers In The Desert (1893) is romantic and evocative. And The Prayer (1877), by Frederick Arthur Bridgeman, makes for a dramatic opening to the show.

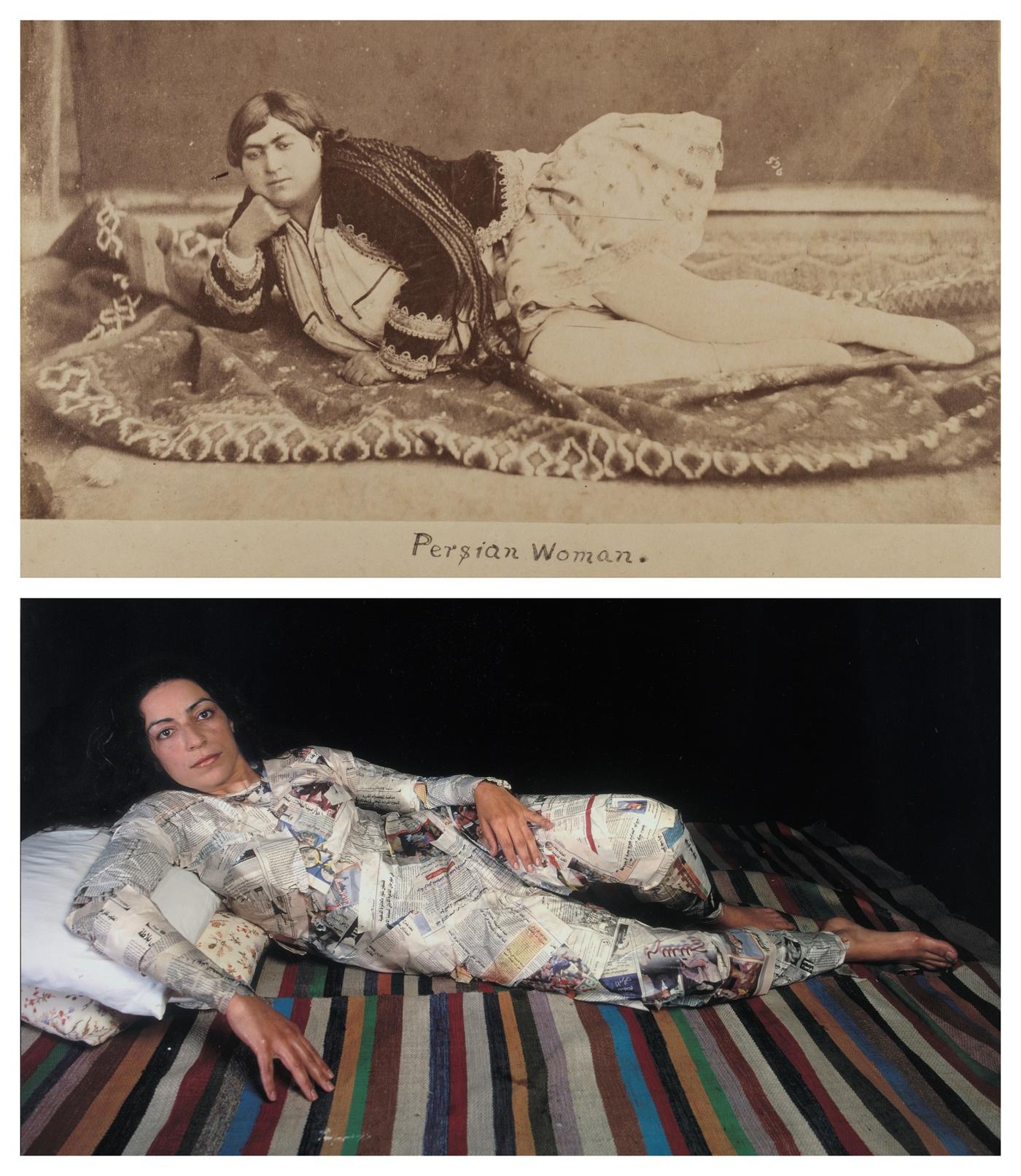

But to focus too much on the Orientalist painters misses the point. A photography section, for example, ranges from pioneering Ottoman photographer Pascal Sabah (1823–1886) to Persian Woman by Antoin Sevruguin (1840s–1933). The latter caught the moment when Nasser al-Din Shah, the Qajar ruler of Iran, became obsessed with ballerina costumes during a trip to Europe - and tutus duly became fashionable among women of his court.

Ceramic works show how the Persian Iznik style influenced European pottery and how Iranian silk shaped Parisian purses. Meanwhile 18th-century Ottoman court paintings of European ambassadors to the empire showed them to be as exotic to Istanbulites as the Ottomans were to them.

In a catalogue essay for the exhibition, the historian John Mackenzie observes that the poet Lord Byron (1788–1824) first used the word “Orientalism” in 1812 to mean simply the knowledge and study of the Orient.

An "Orientalist" has been defined as an expert in Oriental languages, history and philosophy since the 1720s, with professorships of Arabic founded at Cambridge and Oxford in the 1630s. At the time, fear and fascination with the Ottoman Empire seemed a perfectly sensible strategy to many Europeans when Vienna had been besieged in living memory.

The Middle East, the catalogue notes, “has long been Europe’s dressing up box” - and the British public still, it would seem, loves an Orientalist. One politician who has emerged from the UK’s Brexit fiasco with a certain flair is Rory Stewart MP, a dark horse contender for the Tory party leadership and now an independent candidate for London mayor.

Stewart first caught the public eye as an Etonian-educated English gentleman who walked across Afghanistan, ran a charity in Kabul and oversaw a province in Iraq following the US-led invasion of 2003. One portrait of him, on an Afghan hillside wearing traditional robes brought the media nickname “Lawrence of Belgravia”.

While scholars and contemporary artists may treat Orientalism with disdain, the exhibition’s accompanying gift shop underlines its continuing appeal, including colourful hard-bound copies of Aladdin and the Arabian Nights, bars of creamy milk chocolate with Iznik ceramic pattern wrappers, and inevitably, boxes of Turkish Delight.

Inspired By The East: How The Islamic World Influenced Western Art is at the British Museum from 10 October until 26 January.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.