Migration, maps, memory: An artist's journey to a lost Aleppo

Christine Gedeon was three years old when she left Syria.

It was 1976 and her newly divorced mother decided to take her children with her to the United States.

“It was so much easier back then,” Gedeon says. “We got our green card at New York’s JFK airport and in five years had US citizenship.”

Syria was part of the backdrop to her life as she was growing up, but it wasn’t until she was older that she started to become curious about her place of birth.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In 2006, she returned to the country for a visit, spending more time in Damascus than in her hometown of Aleppo. She remembers saying to herself: “It’s fine, I’ll just come back.” Five years later, the war began. Plans for a return trip were shelved indefinitely.

With a physical journey not possible, Gedeon has instead spent the intervening years embarking on a journey through her art. It’s been a deeply personal and painful process that’s highlighted not only a Syria of yesteryear, but a family history shaped by loss, migration and brutal politics.

Gedeon's works - including her pieces on Syria - have been exhibited around the world (she studied art at the State University of New York at New Paltz). Having shown at the Jane Lombard Gallery in New York late last year, her next show in May is a site-specific installation, part of a group exhibition unrelated to her Syria work, at Berlin’s Galerie im Saalbau.

“When the war had started, I felt regret for not knowing the country well," she says. "I was watching the country disappear, it felt like a death, and I would wake up in the middle of the night thinking about it.

"I wouldn’t have worked on anything about Syria or made my family story public if it wasn't for the war. It was the impetus, the motivation,” she says.

Sound and vision

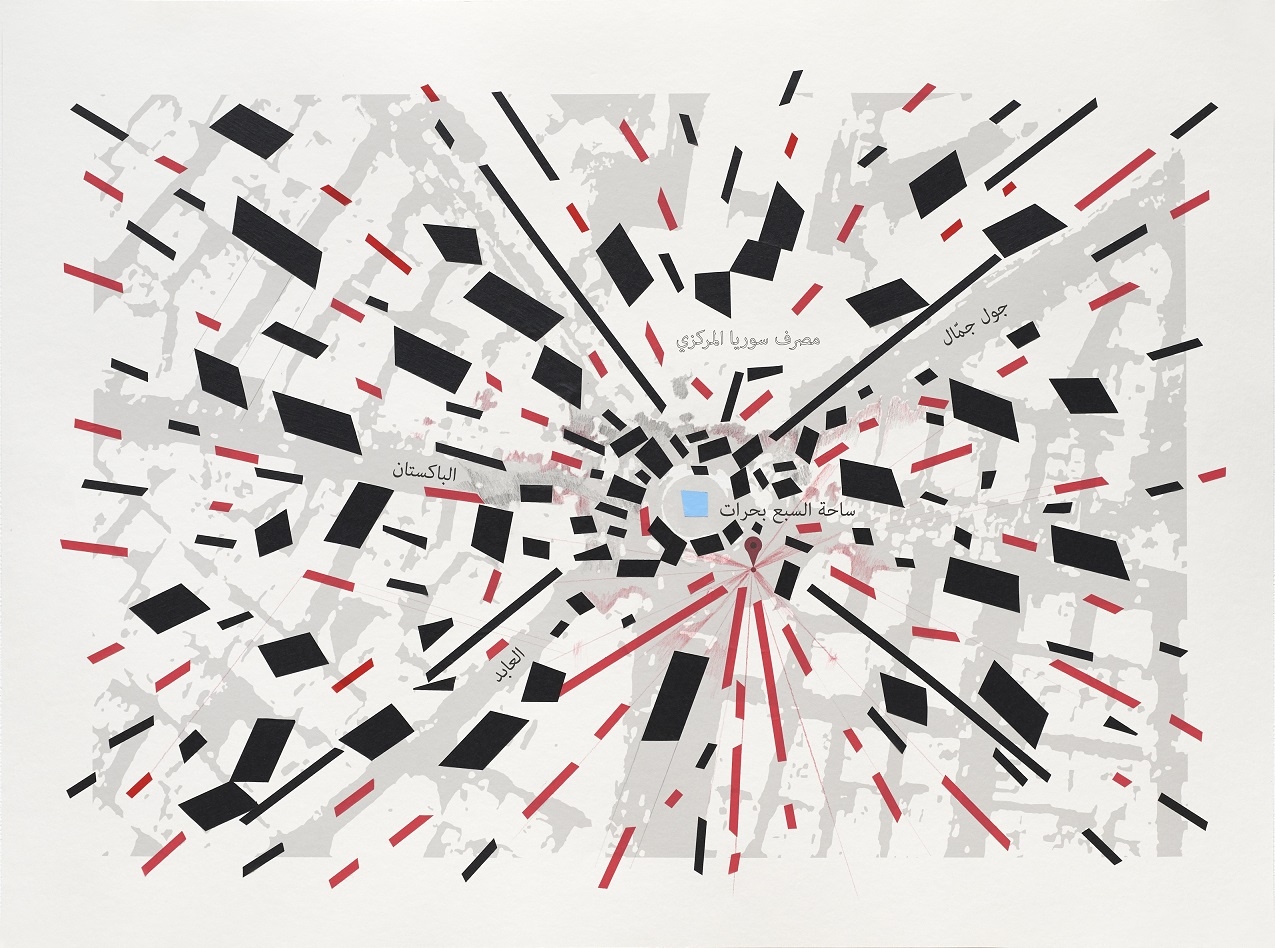

She has worked on three pieces that employ a range of artistic styles and forms such as map drawings with text, stitched work on canvas and a sound string installation to tell stories about Syria that are not often heard in the West. These include her two major pieces, Syria... As My Mother Speaks, and Aleppo: Deconstruction/ Reconstruction.

“I wanted to talk about the vicissitudes of a family history,” she says. “People migrated to Aleppo, then the French were there and there were some golden years for a while. The focus on Syria has just been about this war and destruction and the refugee problem. I wanted to steer it into a different conversation, which also touches on the history of what led up to the war.”

Syria... As My Mother Speaks is a collaboration with Danish sound artist Bent Bogedal Christoffersen. Described as an interactive string instrument, it plays snippets of conversations with her mother talking - mostly in Arabic - about the war and her memories. In the background, sounds of conflict, along with traditional Syrian songs and chants, can be heard.

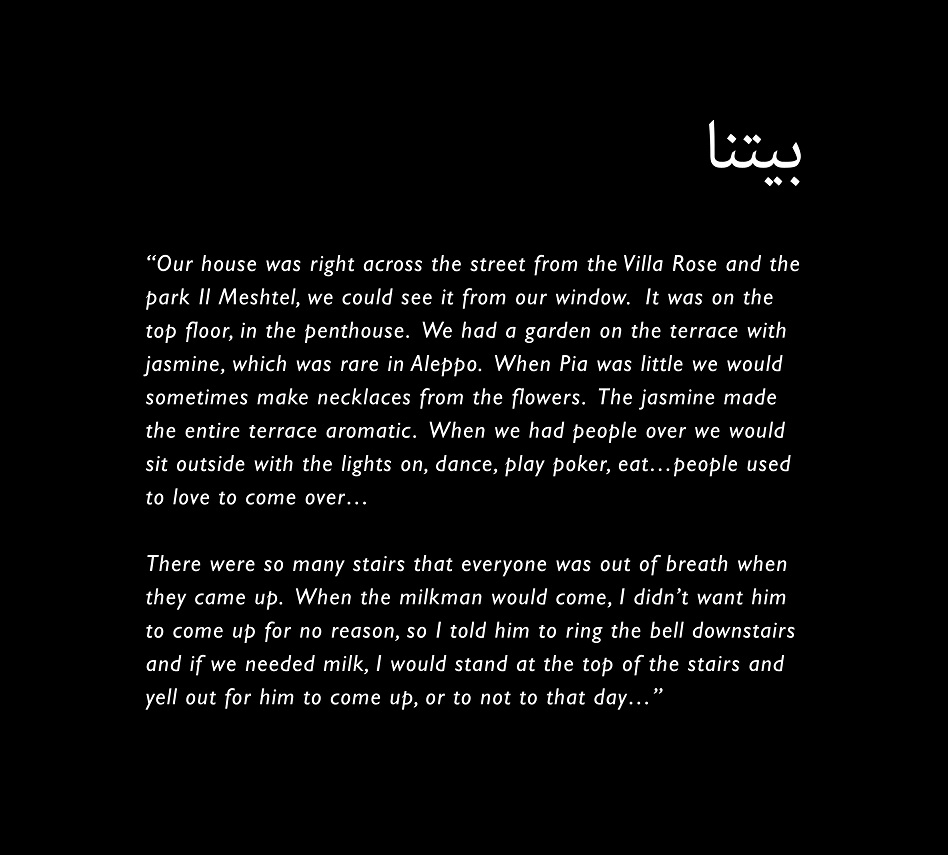

Gedeon’s second piece is a series of 15 works on paper that look at the places, such as the hospital, which is now a villa, she and her siblings were born in and her grandfather’s office, that form a part of her family history, primarily in Aleppo.

With help from family members, who shared the locations on Google Earth, Gedeon worked on them as digital drawings before incorporating tape, pencil and thread.

Accompanying the map drawings are family stories and memories. “It was through attaching stories to maps that I felt I could make something concrete and tangible, solidifying our stories in a way.”

These are stories, Gedeon says, that many people in the region can relate to. Her mother’s side came from Mardin, in what is today in the south of Turkey, and her grandparents made their way to Aleppo during the First World War. Her grandfather owned cotton, tobacco and rice fields, as well as a silk factory in Lebanon.

"My mother's parents were Syrian Orthodox, but since she and her siblings were in a private French school since she was young, she identified more with the Catholic church," Gedeon explains.

Her father’s family were Catholics from Zahle in Lebanon. It is thought they moved to Haifa in the late 19th century, where her Lebanese father was born in around 1928. There they owned several properties, including an arak distillery and a bakery. But they were forced to flee in 1948 due to the conflict that surrounded the creation of Israel.

'I knew that I had this shadow of my identity, that's how I saw it. I didn't really feel American. I didn't feel Syrian'

- Christine Gedeon

In 1958, when Syria and Egypt briefly united to create a pan-Arab state, Gedeon’s grandfather was among those who had land seized. The family lost everything. A few years later, her grandfather died.

Gedeon’s father then travelled to Aleppo, where he met his future wife. Three children followed but the marriage was not to last. However, divorce wasn't recognised in Syria. Gedeon's father had Lebanese nationality so they arranged the paperwork there.

"When we moved to America," Gedeon recalls "my mother was a single mom with three children. I was three, my sister was 13, and my brother was 16.

"The community [we were from] in Aleppo was small so people would talk, plus there were no real opportunities for a single mother there. We had family in the US who had moved in the 1960s and they were able to sponsor us, so we went.”

The missing uncle

In 1978, two years after the family had arrived in America, they received a call from family in Syria with news about Gedeon’s maternal uncle, Michel.

“Michel had just returned to Syria from France, where he had been studying to be a doctor in Toulouse. Somebody had either seen him, or was with him, in the Seven Fountain Square in Damascus. A military jeep had pulled up next to him, asked if he was Michel and that was the last time anybody had seen him.”

When it came to the regime of President Hafez al-Assad, father of current leader Bashar, such stories were not uncommon.

Four decades since his disappearance, the family have yet to discover why he was kidnapped. One theory around the kidnapping appears the most likely.

“One day Michel went to the Syrian embassy in Paris. He had forgotten that once he stepped into the embassy, he was not in France anymore, he was in Syria. One story is that inside, he saw a big poster of Hafez al-Assad and swore at it. The embassy worker allegedly turned to Michel and said he was going to suffer a brutal fate for that.

"We found out later that this guy also worked for the secret service, so Michel had got into an argument with the wrong guy. Hafez wasn’t in power when Michel left and in the years he’d been out of the country it had gone from bad to worse, but Michel had no idea.”

Gedeon says her uncle was probably killed in 1981 in Syria's notorious Palmyra prison. “We don’t know, these are just theories, and after 40 years, we don’t think he is alive, nor do we hope for him to still be alive. I mean, what kind of life would that be? He was a cool guy - a thinker, open-minded, fun and playful. The family loved to be around him."

The shadow identity

From the early 1980s onwards, many of Gedeon's maternal relatives - including her grandmother and uncle - began relocating to the US.

Gedeon and her family had settled in Bergen County, New Jersey, around 30 minutes away from New York. There was a large Middle Eastern community nearby and a Syrian Orthodox church that her grandmother would often visit. Even during these years before the war, Gedeon says that there was always a dark cloud around Syria.

'I don’t know if the works have offered healing or if they’ve just brought back memories'

- Christine Gedeon

“Before my grandmother died, I remember her saying: ‘Why would I ever want to go back to Syria? First they took my husband and then my son away from me’.

"She told me that she had written a letter to Basil al-Assad, Bashar’s older brother, asking for his help to find out what had happened to Michel. He actually agreed to meet with my grandmother, which is strange - whether he was going to or not we don't know - but he did say he would. But a week before they were meant to meet, he was killed in a car accident. That made her lose all hope of ever finding out what happened.”

She recalls finding it hard to identify as Syrian as she was growing up. “I didn't embrace being from Syria. That wasn't really a part of me. I knew that I had this identity, this shadow of my identity, that's how I saw it. I didn't really feel American. I didn't feel Syrian.

"I didn’t feel Lebanese, I didn't know what I fit into. Growing up my mother would speak to me in Arabic, but I wasn't really interested in the language until I was about 18 when I felt regretful for not learning it earlier.”

In the last ten years, Gedeon has produced stitched works on invented spaces related to maps and areas that have been rebuilt in New York. Since then she has also expanded into tape and string installations.

Gedeon says that she will continue to work on Syria-related projects, potentially on those about its future reconstruction. She is also considering a profile project about her uncle Michel, tying it into an investigation about what happened to him. She says her family have been supportive of what she has done so far.

“I don’t know if the works have offered healing or if they’ve just brought back memories. I don’t think my family will ever fully heal, it's more of an acceptance. What’s tragic is that we never knew why he was kidnapped, or when and if he died, so there’s been no closure.”

She describes her relationship to Syria itself as abstract.

“My family history is tragic, but there are many people from this region who have similar stories, so I feel more connected to that now than to Syria.

"The destruction from the war is one aspect to the maps, places and memories, but in a way, I also wanted to project the trajectory of my family story, which could also be read as universal.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.