Houses of memory: Inside the abandoned buildings of Beirut

Beirut's abandoned buildings are ghosts of its scarred past, and Gregory Buchakjian has inhabited hundreds of them - symbolically that is.

The Lebanese artist and art historian reconstructs the stories of the buildings and the people who inhabited them in his first European showing of Abandoned Dwellings of Beirut, at the Boghossian Foundation in Brussels.

First exhibited in the Lebanese capital's Sursock Museum in 2018, the opera gives its witnesses a glimpse of a place “ceaselessly destroyed and rebuilt”.

Born and raised in Beirut of Armenian origin, Buchakjian decided to “symbolically inhabit” these buildings in order to bring their memories back to life.

The exhibition is a rich portrait of a changing city that he says has “witnessed a cycle of unbridled growth, war, economic and social crises and migratory movements” in the last 150 years.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Some buildings, shattered by war, have lain empty for years, waiting for the next building boom to reach them, while some have languished in ownership disputes. Others have become monuments in their own right, like Beit Beirut, an infamous former sniper’s lair refashioned as a cultural centre.

Between 2009 and 2018, Buchakjian - director of the School of Visual Arts at Lebanon’s Academie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts - and dozens of volunteers visited hundreds of buildings, both photographing and sifting through the ruins for documentary materials.

About 30 percent of the buildings chronicled in his project have since been demolished, he estimates. “It cannot be precise and it changes all the time. I cannot check these houses every day.”

When form meets function

The Brussels setting is a meaningful one. The Boghossian Foundation itself was brought to life in a major overhaul of an abandoned Art Deco masterpiece, the Villa Empain. The mansion built for Baron Louis Empain in 1930 was subsequently occupied by German soldiers, used as the Soviet embassy, and then by a television channel.

The building was left mostly empty until the foundation bought it for transformation into a gallery and centre to promote closer ties between eastern and western cultures through the universal language of art.

In 2017, Jean Boghossian, the artist and foundation president who represented Armenia in the Venice Biennale, staged a striking show of his artworks, shrouded in fire and smoke, at the L’Orient Le Jour building in Beirut. In a central district undergoing rapid development, it remained a shot-out shell still marked by fighters’ graffiti and shell holes used as sniper’s nests.

Louma Salame, general director at the foundation, said: “Buchakjian’s work echoes our mission in a very powerful way, particularly given the current situation in Lebanon. The scientific rigour, as well as the melancholy, the poetry that emerges from his art struck me when I discovered it in Beirut and I wanted to show it to our visitors, curious about the history, the art scene and the current events in the Arab world.”

Suspended spaces

One of the most fascinating houses in Beirut, Buchakjian says, is Qasr Heneine, the Heneine mansion or palace.

“It’s a house that was built for a Russian aristocrat, Tordoski, in the mid-19th century. This Russian gentleman decorated it in a style inspired by the Alhambra, or palaces in Damascus and Aleppo. It’s very Orientalist, and at this time the Lebanese bourgeoisie was moving in the opposite direction. They were making houses in the manner of Venice or Paris, with neoclassical or neo-baroque decoration."

In the 20th century, the house was rented by a French doctor, who was then expelled from Beirut in World War I, followed by the US and Dutch consulates taking over.

The magnificently decorated building was then transformed into a restaurant before five Shia refugee families made their homes there in the Lebanese civil war. Now listed with the World Monument Fund, and divided between several owners, it remains “in a suspended situation”.

Amongst other discoveries, the hunt for archival material from the house turned up a set of diaries from a schoolteacher (named in the archive as Victoria K) who lived at the house, which included references to the Lebanese political crisis of 1958 when the US staged a three-month military intervention to prop up a pro-western president.

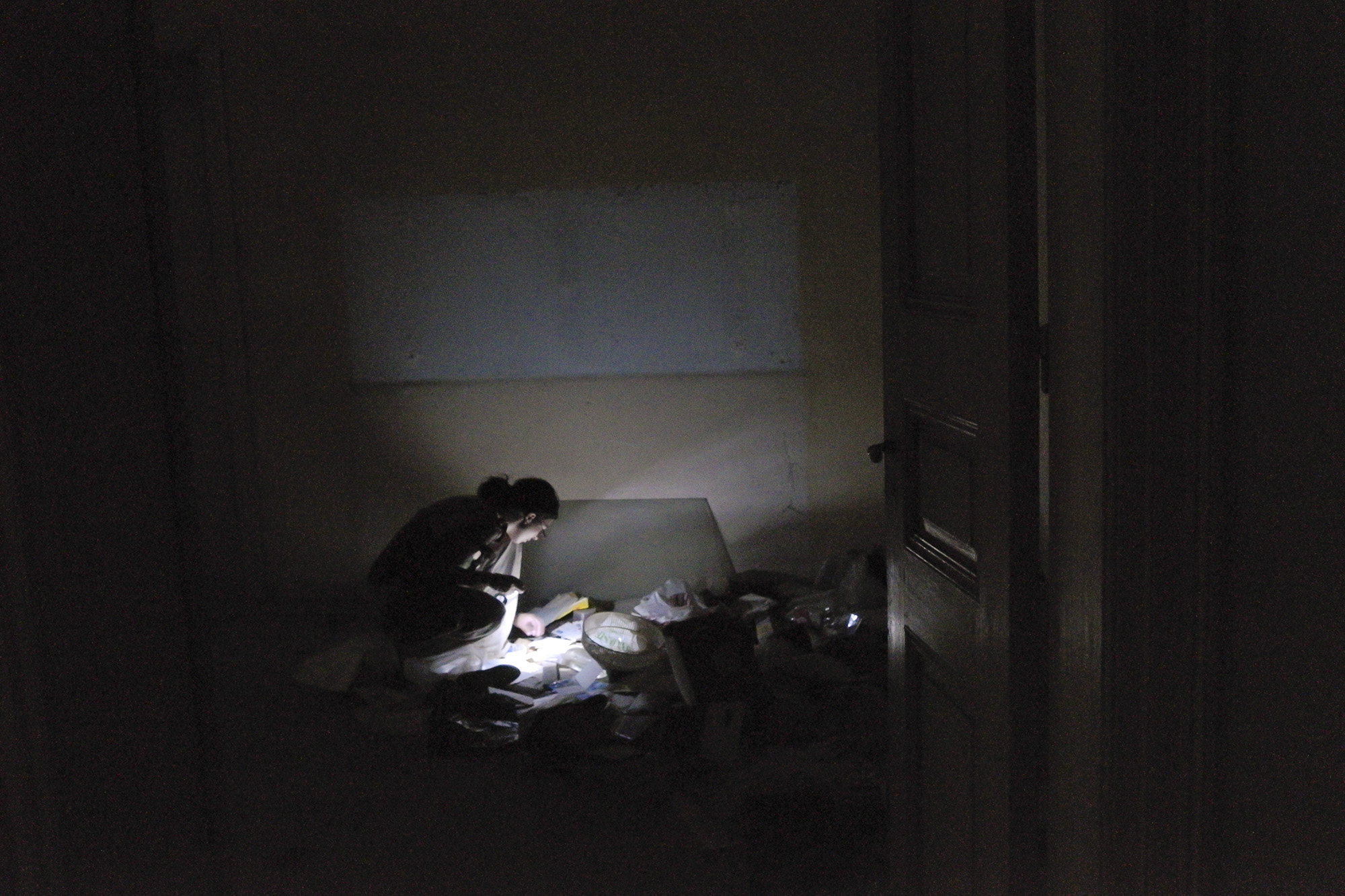

Valerie Cachard, a prize-winning playwright and performance artist, is shown in the photos exploring the house.

“Valerie who is a writer and performance artist was one of the first women I photographed for the project. Later on she actively accompanied me on field exploration. She is the one who initiated the collection of archive documents from the abandoned houses,” Buchakjian said.

The use of people to “inhabit” these abandoned spaces was inspired by Maroun Bagdadi’s 1980 film Hamasat (Whispers), about the lives and voices of Lebanese during the war. In Bagdadi’s work, poet Nadia Tueni wandered the ruins of central Beirut.

The house of Takieddine el-Solh

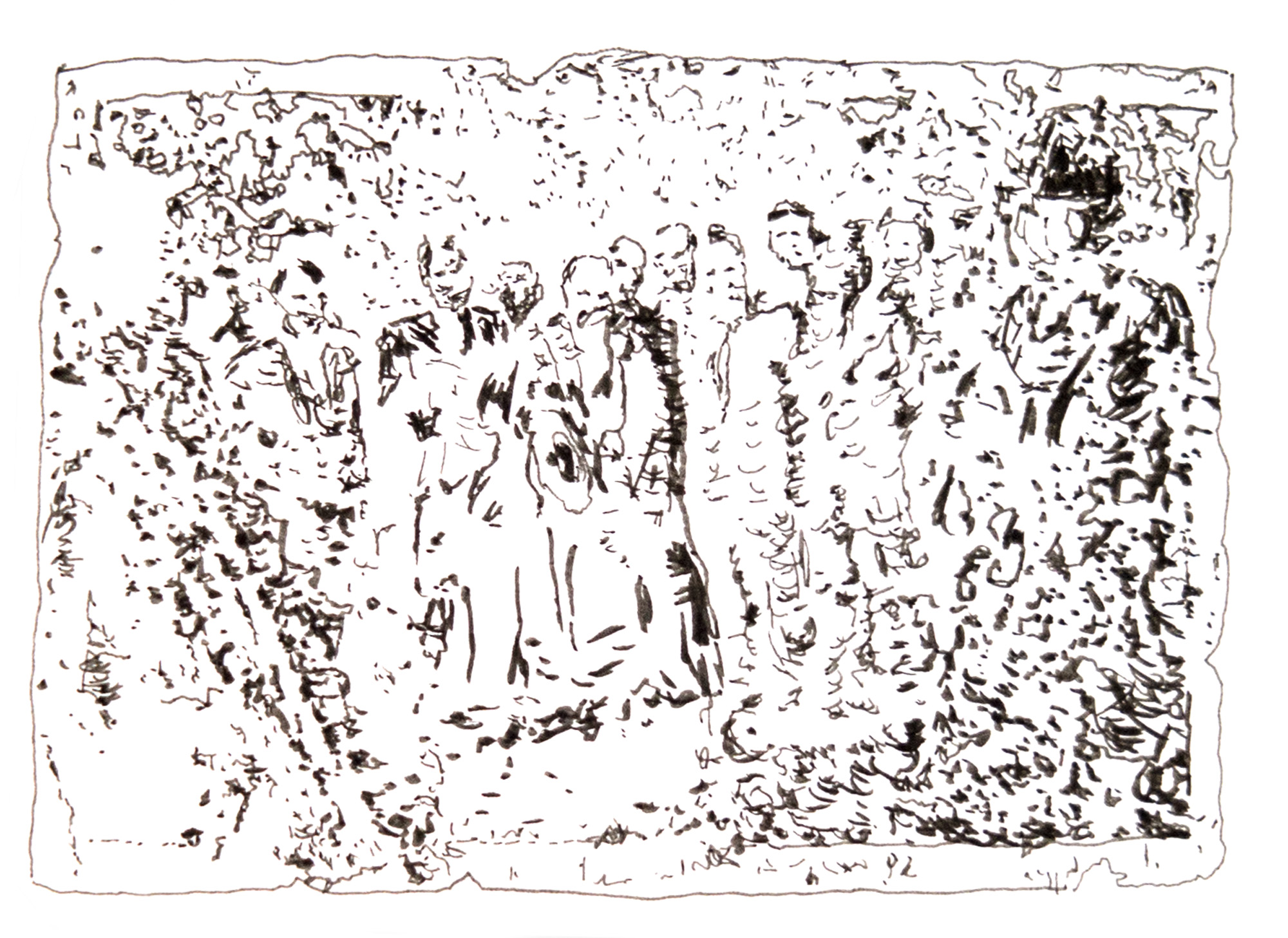

In a new body of work produced specifically for the Brussels exhibition, Buchakjian made a group of five drawings as part of the project, adding texture to the materials taken from the house of former Lebanese prime minister Takieddine el-Solh, with a particularly rich and dramatic history.

“Instead of having the original document, it is having somehow its ghosts, its imprints,” he said.

The house was inhabited by the local Ottoman governor, then later by leading political figures from the Sunni community, notably el-Solh, who served as the 23rd prime minister of Lebanon from 1973 to 1974, and again briefly in 1980.

It functioned as “a witness” to assassination and civil war. In 2014 a man was abducted, imprisoned and then murdered in the house, with his murderers burying the remains there. “The drawing is based on a picture I found in this house, and a group of men among them is a politician who was prime minister,” he said.

An entire room in the exhibition is devoted to the house and its history, with three installations, including a diptych of two pictures, one by Fouad Elkoury taken in 1984 and one by Buchakjian in 2016. Elkoury became known internationally for his pictures of the Lebanese civil war.

In the image by Elkoury, the house is luxuriously furnished and inhabited. El-Solh on the left wears his tarboosh - Ottoman headwear - while in conversation with a guest. Buchakjian’s photograph of the same desolated space is barely recognisable.

The 'Pink House'

The “Pink House”, a residence built in the mid-19th century on the western edge of Beirut, is a landmark construction near the lighthouse, overlooking the sea.

The ground floor - which is the oldest part (two floors were ultimately added) - was the studio of Sami El Khazen, a prominent Lebanese artist and designer in the 1970s and 80s. He died in 1988.

This was a place for working and partying, inspired by the swinging 60s and by the Orient.

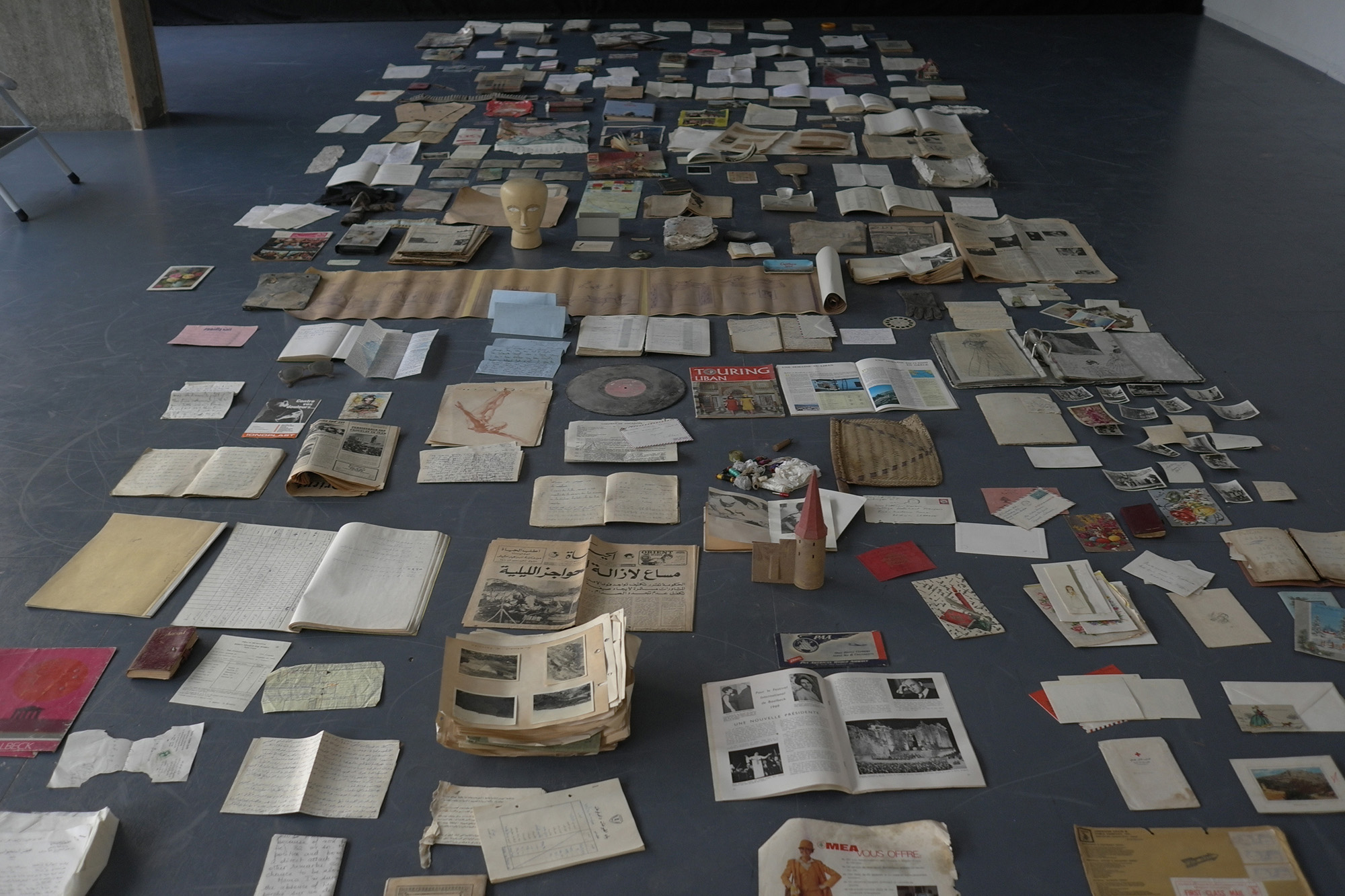

The Brussels exhibition has a lot of pieces that were not in the original Beirut showing, Buchakjian says. The materials they had access to included letters, personal diaries, newspapers, postcards, legal contracts, passports, identity cards, and old airline tickets.

“In some houses, there was so much we could not take everything. But thanks to these documents, we were able to reconstruct the stories of many of these houses."

Buchakjian continues to chronicle the historical geography of Lebanon at the Academie Libanais des Beaux-Arts, with student programmes to “meet the challenges of our early 21st century: environmental degradation, massive destruction - including of cultural property”.

The place that remains

Representing Lebanon at the Venice Architecture Biennale last year, he showed his travel photographs as part of a project, The Place that Remains, tracing the outline of the Beirut River and exploring the uses and future of the urban landscape. The line sometimes coincided with the demarcation lines between rival fighting groups in 19th and 20th century wars.

“I met a lot of people through the exhibition,” he says. “I think what these pictures and the whole project has to say, it’s the story of Beirut but it’s the stories of cities of the 20th and 21st century. The way cities are transformed."

But the subject had to be his city, he says. "I would not have done the project about any other city because I know it better than any other city. But these [visitors] never came to Beirut in their lives. These pieces are somehow universal.”

Buchakjian's research produced a PhD thesis at the Sorbonne in Paris, an archive, a book, an exhibition and a film. The work on the ground is a chapter that has closed, but it has left enough to create a series of exhibitions, he said.

“The project could last for your life. Each time I could create new pieces, with the materials I have gathered. We will see where it will go after Brussels,” he said.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.