Cannes Film Festival: How 'The Brink of Dreams' reveals much about Egyptian Coptic life

A public street in the Upper Egyptian town of Deir El-Bersha in Minya. The words “The Bus of Dreams” are handwritten on a white piece of paper erected on a pole attached to a bench.

Five twenty-something women are dressed in modest outfits, donning face veils made of transparent striped paper.

Each of the five voices have different yearnings: “I dream I would be a rich, famous singer,” one says. “I dream of walking freely in the street,” another adds. “I dream of directing a grand theatrical production,” the third, and most effervescent of the five, yells.

Idle onlookers appear to be engaged but bemused. The kids are respectfully silent, struggling to figure these girls out. And in the most pointed moment of the sequence, one girl defiantly asks: “Why don’t you believe us? Why don’t we believe ourselves?”

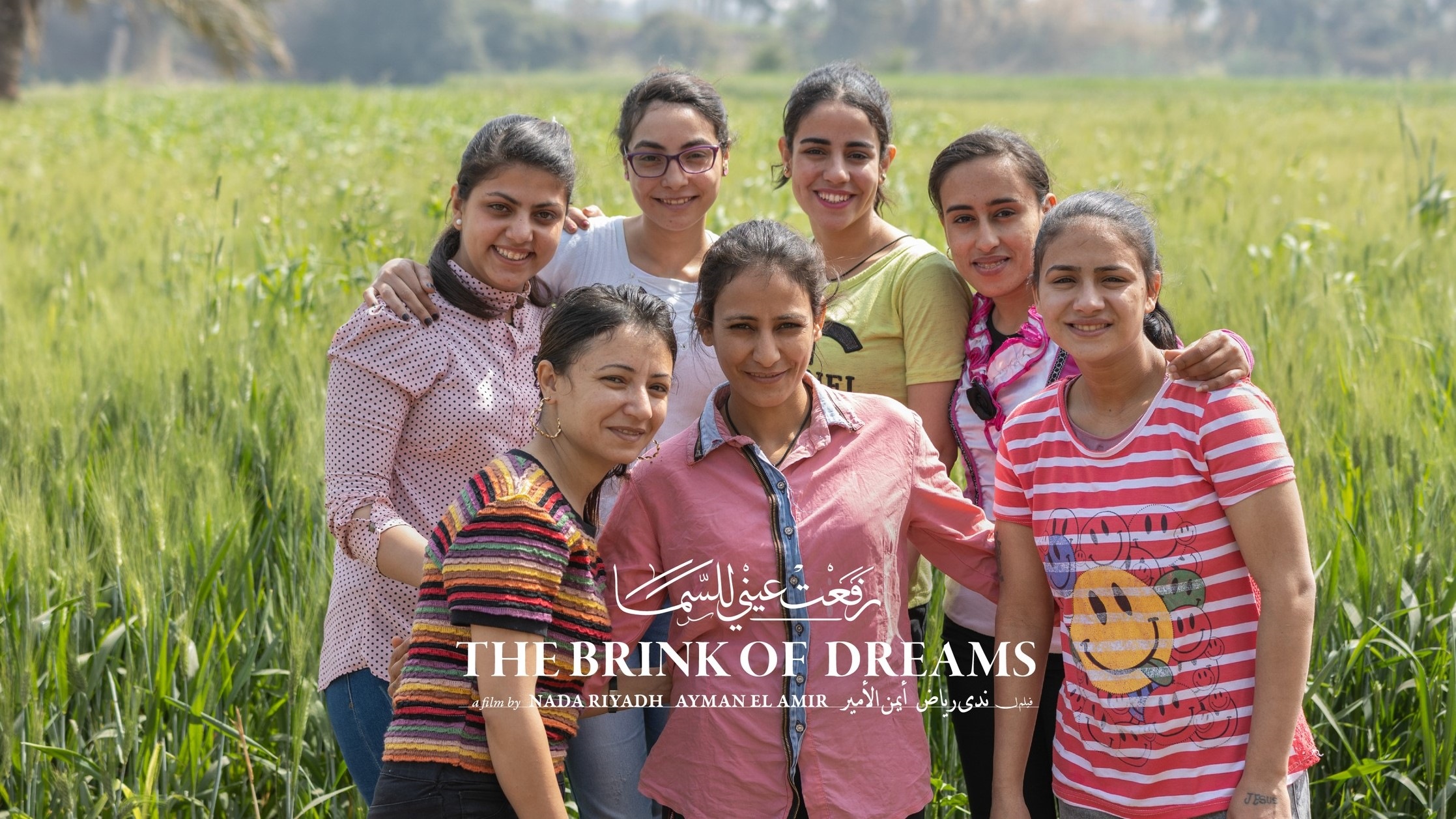

The girls are the protagonists of the 'Oeil d'Or prize winning The Brink of Dreams, Nada Riyadh and Ayman El Amir’s piercing, bittersweet documentary premiering in late May at Cannes’ Critics’ Week sidebar.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Having the distinction of being the first Egyptian non-fiction film to be screened at the festival since Tahani Rached’s El-banate Dol in 2006, Riyadh and El Amir’s sophomore feature is a coming-of-age story, an endearing portrait of female solidarity and an astute study of small-town Egyptian life.

Most importantly, it is one of the most revealing records of Coptic Christians, Egypt’s largest religious minority which continues to be misrepresented or deliberately discarded in both film and TV.

Minya is distinguished for having one of the highest concentrations of Coptic Christians in the country, comprising half the population of the southern city.

Unlike Asyut, the more affluent southern brethren, Minya is more distinctly conservative.

Strict, regressive rules continue to govern gender relations; the woeful economy eliminates any space for the kind of class ascension associated with progressive values.

‘You are useless’

The young women’s artistic dreams are simple but ambitious. One aspires to be a singer; another a ballet dancer; a third an actor. They dream of love and fame and financial success. They strive for equality and tussle with members of their community to take them seriously.

They decide to form a theatre troupe. With the government utterly discarding culture and closing down the already impoverished art spaces in underserved places like Minya, the women find no public place to perform but the street.

The role of the church is conspicuously ignored by the directors. For Coptic Christians, especially in underprivileged cities like Minya, the Orthodox Church plays a central role in its followers’ lives, not just spiritually but economically and politically as well.

Theatre is an integral part of the church’s outreach programs, but they’re strictly confined to passion plays and artless Christian preaching.

The secular dreams of these young women do not fit within the narrative and rhetoric of church theatre, which is why the egalitarian space of the street becomes the only avenue for self-expression.

Their little sketches are unsurprisingly primitive and raw: direct, unfiltered expression of their frustrations, fears and thwarted desires.

Still, their adamancy on self-actualisation stands in contrast with the attitude of the younger men around them.

Earlier in the film, Majda, the leader of the group and the most head-strong figure of the bunch, is scolded by her brother for doing theatre. “You’re all useless. What you do [theatre] is obscene,” he tells her. “Your only place is at home.”

Kirolos, the fiance of Haidy, the meekest member of the lot, is no different. He frowns upon the group, accuses his fiance of having “a weak personality”, exploits her love for him in order to ostracise her from the group and does nothing but control every facet of her life.

Haidy’s father is more progressive than Kirolos. He encourages her not to abandon the group and questions her decision to get married at such a young age.

Her father belongs to a generation that treated women’s liberation as a means for financial independence and manifestation of what they deemed as good Christian parenting.

The cash-strapped younger Christian men are less broadminded than their parents. Their chances of realising the more expensive and more demanding urban life is out of reach thanks to Sisi’s classist, cavernous neoliberalism that has severely increased the gap between the rich and the poor.

Inability to control one’s destiny has led to an increased appetite for controlling women,the only available domain these young men can have some say in.

The church and the status quo

Religion continues to give Egyptian men this authority, although the film never reveals the position of the church in the subjugation of women.

In one scene, very telling in how it’s edited, El Amir and Riyadh underline the wedding vows where the priest tells one of the girls to “follow your husband’s orders” and to “always greet him with a welcoming smile and never disobey him”.

With censorship hardening during Sisi’s reign, stories containing church critique or pinpointing sectarian discord are instantly thwarted

With its close alliance with the current political regime and incessant adherence to unbending traditional values, the Coptic Church has become a vehicle for maintaining the status quo, and not rebellion.

Women’s rights are safeguarded, but always within that traditional family structure. Deviation from norms is not allowed, nor is it tolerated.

In the absence of government help, the church has filled the gap for social security, providing work opportunities and support networks for those in need.

It’s not a coincidence that all members of the groups are Copts - a warm bubble the young women never attempt to break away from.

Notably, there is no Muslim presence whatsoever in their lives; interfaith relations, El Amir and Riyadh indirectly imply, have no place in this world.

The reluctance to delve into thornier issues underscores the limitations of depicting Coptic lives on the Egyptian screen.

Coptic representation

Coptic narratives provide a fascinating reflection on the cultural status of Christians in Egypt, the persistent inequalities in parts of the nation, and the church's influential role in shaping the representation of its community.

Christians, who represent roughly 15 percent of the Egyptian population, have been integral to the Egyptian film and TV industry.

Renowned Christian directors include Henry Barakat, Naguib el Rihani, Kamal Attia, Khairy Beshara, Yousry Nasrallah, Daoud Abdel Sayed, Samir Seif, and the late Youssef Chahine, the Arab world’s greatest filmmaker.

Popular actors include the great Sanaa Gamil, Mary Queeny, George Sidhom, Lebleba, Nelly, Hala Sedky, Maged el-Kedwany, Hany Ramzy, among others.

Nonetheless, the considerable presence of Christians in film and TV does not translate into a sizable volume of Coptic stories.

In the first 50 years of Egyptian cinema, Christians were relegated to supporting roles, pigeonholed as the docile neighbour or the depraved foreign other who must convert to Islam to achieve contentment.

The autobiographical tales of Chahine (Alexandria…Why?, 1979) and Nasrallah (Stolen Summers, 1988) brushed religion aside, focusing instead on the intricate dynamics of their dysfunctional families.

It wasn’t until Osama Fawzy’s Baheb el Cima (I Love Cinema, 2004) that Egypt had its full-fledged Coptic story.

A childhood dramedy about a child growing up in a strict Coptic family who finds solace in his love for film.

Fawzy’s acclaimed third feature found itself in hot waters with some factions of the Coptic population for “disrespecting the Orthodox faith”, as 20 prominent Christian figures put it in the lawsuit they filed against the film’s makers at the time.

Infidelity, repressed sexuality, the oppressiveness of religion, and doubt in God are some of the themes Fawzy tackled in his modern classic that some Copts abhor for its unflattering portrait of the church.

The controversy that greeted I Love Cinema discouraged subsequent filmmakers from producing similarly authentic Coptic portraits.

Over the next 20 years, Copts were once again relegated to the roles of good neighbour or patriotic co-worker in Sisi’s post-2014 military propagandas.

There were some exceptions along the years. Hesham Issawi’s El Khoroug (Cairo Exit, 2010) starring a fresh-faced Mohamed Ramadan depicted a forbidden love story between a working-class young Muslim man and a Christian girl in pre-25 January revolution Cairo.

Kamla Abu Zekri’s multi-character drama One-Zero (2009) incorporated a Christian female character fighting to get a divorce.

Abu Bakr Shawky’s Cannes contender Yomeddine (2018) featured a Coptic leper man from Upper Egypt who embarks on a road trip to locate the family that left him behind.

Engi Wassef explored the little-known world of the infamous Coptic garbage-collecting village in Mokattam in the 2008 documentary, Marina of the Zabbaleen.

Not rocking the boat

The latter pic - a US production - is arguably the most incisive and penetrating of the post-millennial Coptic stories, shedding light on class inequality, governmental prejudice, and disenfranchisement of the different Coptic sub-communities.

The sanitised treatment of Copts on screen falls in line with the protective and conservative position of the church towards its followers.

A key philosophy of the Coptic church is that what happens in the church stays in the church.

With censorship hardening during Sisi’s reign, stories potentially containing church critique or pinpointing to the lingering sectarian discord are instantly thwarted. The parameters of what can be shown about Coptic lives therefore remain as limited as ever.

The Brink of Dreams operates within those confined parameters. It doesn’t try to rock the boat or make overt statements about the shrinking options for underprivileged Coptic women.

Instead, it celebrates their resilience, champions their earnest art and grants them that precious space for expression they have long fought for.

The girls are fully conscious that they are the protagonists of their own film, always choosing what and what not to divulge, and assuming full agency over how they’re portrayed on screen.

Moments of projected vulnerability are calculated if not insincere, and the ambience of the film habitually feels like a campfire around which the girls gather to commemorate their friendship.

The camera offers a space for the girls to become whoever they want to be, or perhaps who they really are. Reality ultimately proves too sturdy to conquer or work around as their artistic dreams recede with marriage, family life, and, most arduous of all, adulthood.

El Gouna Film Festival celebrates the Egyptian film The Brink of Dreams, directed by Nada Riyadh and Ayman El Amir, for winning the L'Oeil d'Or for Best Documentary award at the 77th Cannes Film Festival. The film, previously part of the CineGouna Springboard. pic.twitter.com/r8u7W18z76

— El Gouna Film Festival (@ElGounaFilm) May 24, 2024

Largely composed of medium shots and close-ups of the girls’ faces, Riyadh and El Amir show little of Minya, rendering the girls’ art a cocoon they have conjured up to shelter themselves away from their external static, restrictive surroundings.

Various coming-of-age films are invoked: Terry Zwigoff’s Ghost World; Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird, and especially Federico Fellini’s classic I Vitelloni - emotive accounts of young people struggling to break free from small-town life.

The narratives of these films follow a similar arc: friends grow apart, destinies diverge, and a lone wolf finally manages to part ways with the pack and leave.

The Brink of Dreams follows the same arc. Members of the group get married, entrench themselves in the incapacitating domesticity, and discard their dreams. Majda is the sole member of the group who refuses to conform to this mundane existence as she moves to Cairo in order to pursue her dream of acting.

For devout Christians like Majda and her cohorts, the church will remain present in their lives. She will continue to find support in one of the few functional social institutions in the country - a sanctuary for when the going gets tough.

But it may no longer play the central role it once did. As more young people move away from an establishment with an outdated ethos and a queasy partnership with a political regime that has worsened their lives, the Coptic church may no longer represent for millions of young Egyptian Christians anything more but a tranquil place of worship.

The Brink of Dreams shies away from providing a comprehensive socio-political context for the stories of its women protagonists; perhaps no film made in Egypt by Egyptian filmmakers can.

But the compassion it offers in spades, the arresting Coptic faces it revels in, and the spiritedness of the women it espouses, makes it a worthwhile and essential entry into the still small pantheon of Coptic-centric films.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.