Death of a writer: Murder casts shadow over Baghdad's literary scene

In the centre of Baghdad International Book Fair fair, statues made from the pale ghostly pages of books stand atop piles of more books. Their heads are mirrors and fascinated attendees step up to take pictures of their reflections staring back at them.

The atmosphere is warm and bustling, filled with young fairgoers excitedly thumbing through new books.

Sociologists, historians, poets and novelists are sitting in booth after booth of books. Fans line up to take selfies and get signatures from their favourite authors.

The stalls are named for the style of literature they host, featuring books on the ever-shifting mores of political control in Iraq. One is “House of Fantasy,” another the “House of Egypt” and another “The House of Power”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But in a quiet corner, there is a medium-sized poster of a middle-aged man in a light grey houndstooth newsboy cap: his name is Alaa al-Mashzoub. A month ago, he was assassinated when three men shot him down as he was bicycling back to his family home in Karbala on 2 February.

The police have not arrested any suspects in the murder. His assassination sent shockwaves through Iraq’s tightly knit literary scene and it lurked as a silent shadow in the hustle and bustle of the fair.

Prolific writer and critic

Al-Mashzoub published 30 books over the course of his life and completed four more that are yet to be published. He wrote novels that were full of his native city of Karbala and documented its history and people.

Al-Mashzoub also spoke frankly and openly about almost any topic - freely criticising Iran, politicians and the local militias that dominated his city.

“He wasn't afraid, ever. He spoke with all his power with ease. He was a hero. He wasn't afraid of anything,” says Mohammed al-Saadi, one of al-Mashzoub’s publishers and a friend from Karbala. Al-Saadi runs a bookshop in the city and first got to know al-Mashzoub as a frequent customer. They became friends and al-Saadi was one of the first people to publish his books.

“He [Alaa] came from a poor family that did not have money,” says al-Saadi, “He left business and went to the cultural life. He was very close to the people. He was an author of the poor. He would sit on the sidewalk.”

Alaa was known for sitting at the public cafes in Karbala at a place dubbed the “culture sidewalk”, where he would sip sugary tea, smoke cigarettes and loudly criticise anything from the religious authorities in Karbala to the influence of Iran.

“He spoke a lot and strongly,” says Salah Tellawi, a Jordanian publisher of Mashzoub who is in Baghdad for the Book Fair. “I would be afraid. I would not say or discuss these things. He did not have this problem.”

Literature, Iraq's pride

Literature holds an exalted place in Iraq. People treat poets like celebrities, crowding around them and trying to say hello or take a photo.

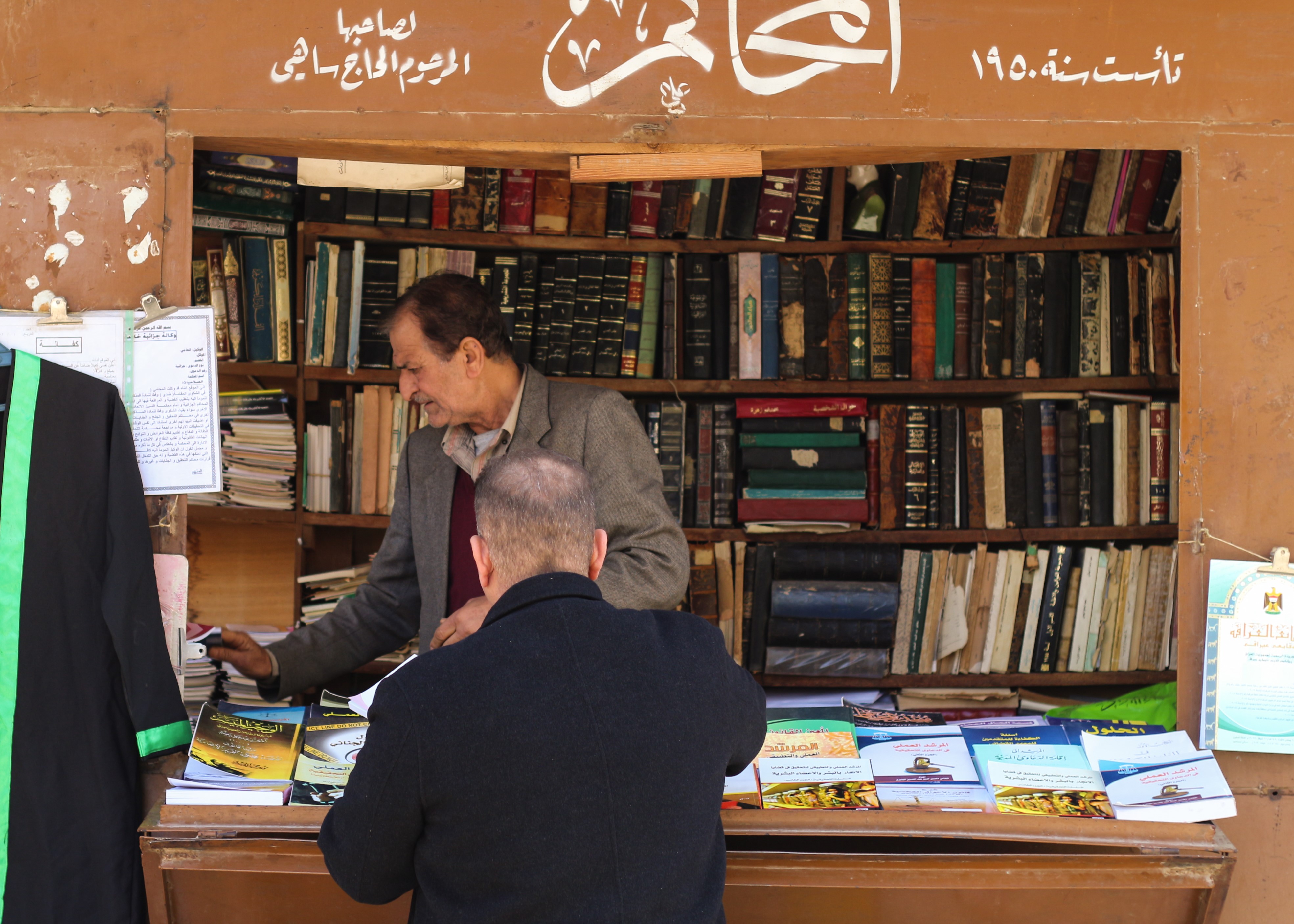

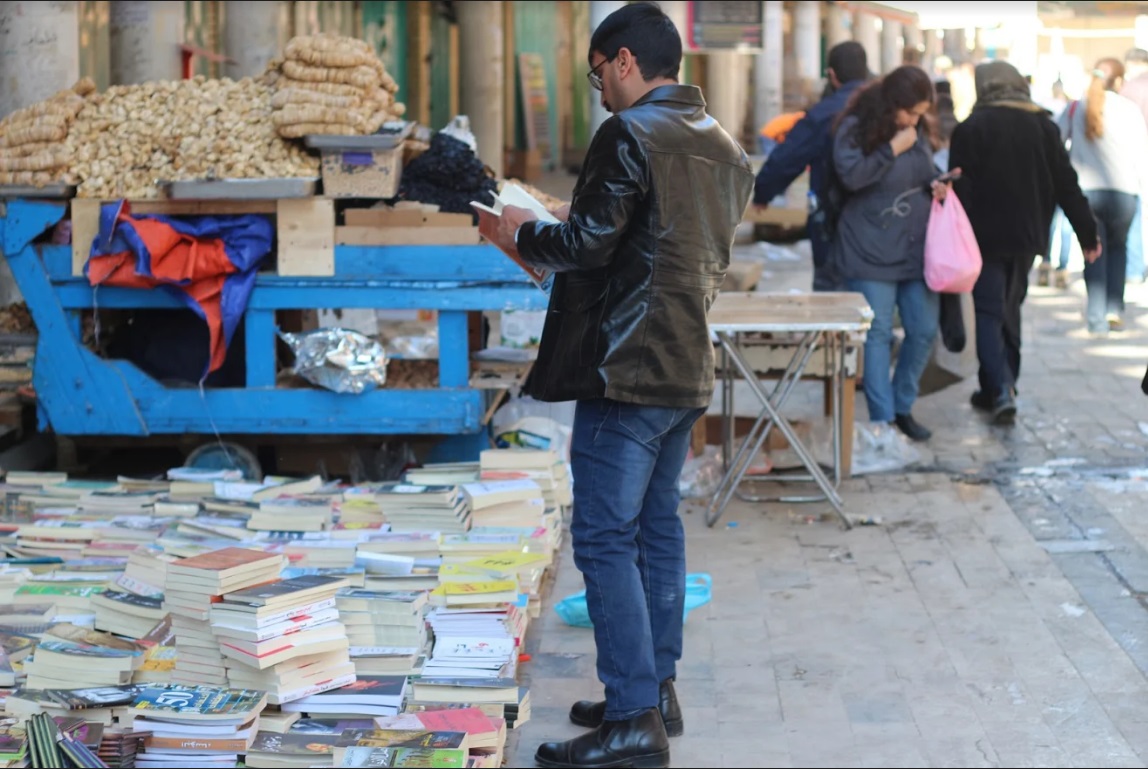

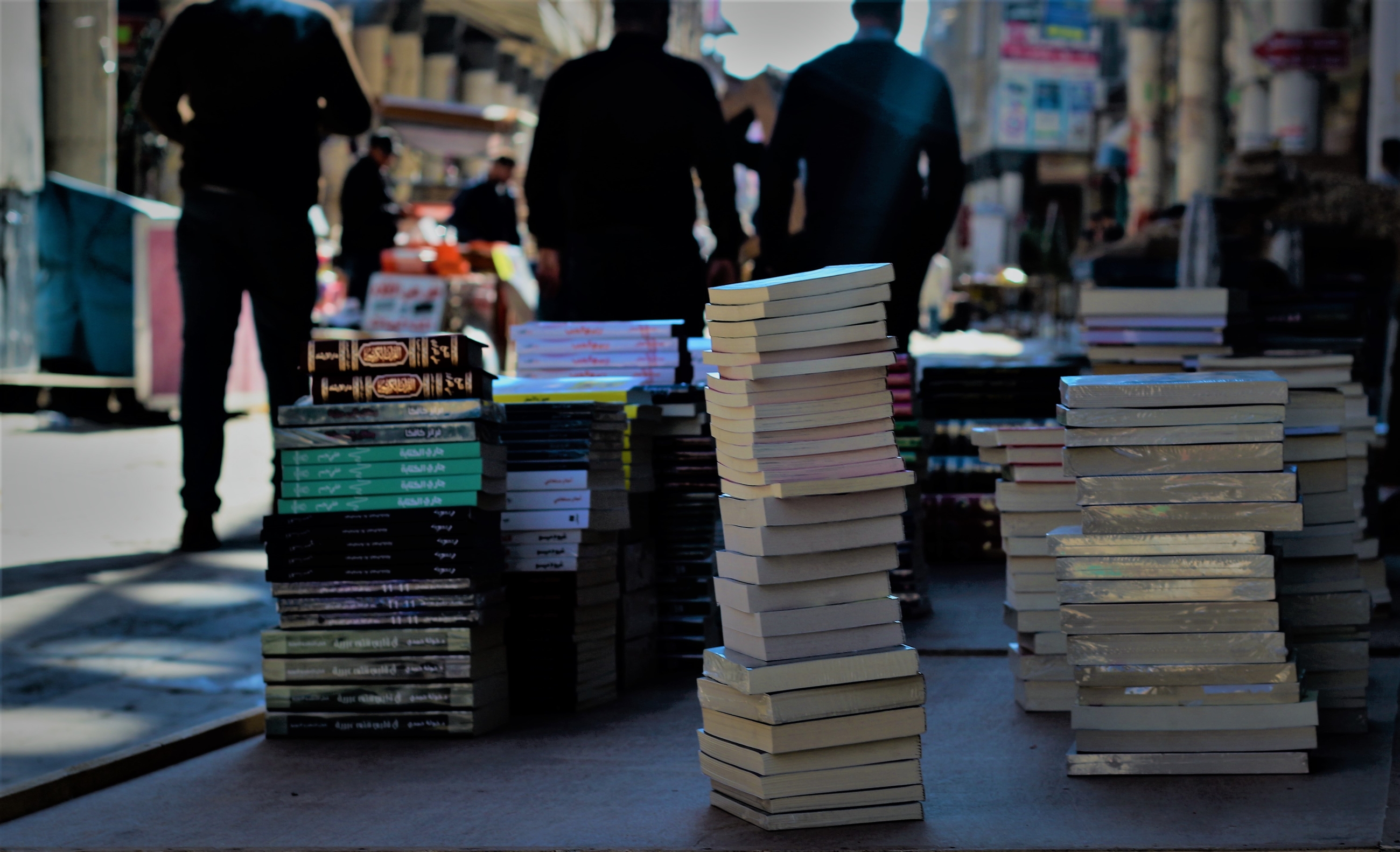

Every Friday, the city’s historic book market on Baghdad’s Mutanabbi street opens to crowds flocking to buy books and mingle with the cultural elite. The market overflows with literature with books piled liberally on blankets on the sidewalk, bookstores, and book stalls.

The pavements are littered with books varying from Russian classics to steamy bodice-rippers from the sixties. At the end of Mutanabbi street stands Cafe Sharbinder, a dark, smoky hall with walls papered with portraits of Iraqi luminaries varying from the former royal family to literary legends.

Inside the cafe, there are endless conversations and visits from novelists, playwrights and poets.

Sitting in groups of two or three, the room is a centre for heated debates, history and politics. Polymaths abound with conversations meandering from classical poetry to tribal politics. Criticism flows freely, which is part of the reason why authors were so stunned by al-Mashzoub’s death.

Shockwaves

Emad al-Sharaa, a journalist and media rights activist, felt deeply disturbed by the assassination. Normally his eyes sparkle with humour as he shares anecdotes and jokes, but now his gaze is distracted and distant. Mashzoub’s death shook him.

He sits in Ridha ElWan, another one of Baghdad’s warm literary cafes that has walls lined with books and writers crowding every table. He worries that Mashzoub’s death was a message to anyone who speaks too loudly.

“I was affected, of course, I am afraid... The armed groups do not sleep. But you need criticism to grow, you need criticism for the society,” he says.

After al-Mashzoub died, rumours swirled that he was killed for a Facebook post he made a few days before his death that criticised Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khomeini.

Al-Sharaa says he thinks this is unlikely, as it’s normal for people to criticise Iran. He believes that it is more likely al-Mashzoub was assassinated for his criticism of militia groups in Karbala. But whatever the case, as an investigative journalist, the case has left him both jaded and worried.

“It will continue,” he says exhausted, “any person who criticises will get killed.”

Baghdad’s authors are veterans of such threats, having weathered Saddam Hussein’s tight censorship, the war with Iran, the war with Kuwait, the US occupation and subsequent civil war in the mid-2000s.

After Saddam

Unruffled by news of al-Mashzoub’s assassination, renowned novelist Ghalib al-Sharbinder sits curled up on his couch in his home in Baghdad. Every wall of his small house is lined with bookshelves with endless stacks of worn volumes covering all of the available space. At 75, he has published 60 books and has seen it all.

He says under Saddam Hussein, there was more stability, but less freedom. According to Sharbinder, people were watched and saying the wrong thing could result in a death sentence. That era left a lasting mark on Iraq’s cultural scene, and many of the deep thinkers fled the country.

After the 2003 American invasion of Iraq and the toppling of Hussein, the restrictions that once existed on publishing were lifted and it allowed for a renaissance of ideas. Al-Mashzoub himself did not start writing and publishing novels until after Saddam had fallen.

“There aren't red lines in Iraq now. If you go to Mutanabbi street, you can see tens of books against God and tens of books for God,” says al-Sharbinder.

Tellawi, al-Mashzoub’s publisher, disagrees. He says that while most things can be discussed and published openly, there are red lines. “There are few people who will speak with full honesty...There are limits. There are red lines. No thinker or any writer can cross these limits,” he says.

Silence around the edges

At Baghdad’s Book Fair, no one wants to mention names when they speak about who may have killed al-Mashzoub. They mention militias, armed groups from Karbala that are connected to Iran. But few want to make specific accusations. The silence around the edges of the conversations speaks for itself.

'Of course, some people are afraid, some flee. But the old thinkers face death with strength'

- Ghalib al-Sharbinder

Even al-Sharbinder acknowledges that it was most likely al-Mashzoub’s tongue that got him killed. He thinks that the freedom that came after American occupation was accompanied by chaos, which allows for impunity. He dismisses the idea that al-Mashzoub was killed for having critical opinions. He believes he was killed for the way he expressed those opinions.

“He spoke in a very strong way, 'I am against Iran,'" says al-Sharbinder, “That’s known. I also talk about being against Iran on the television...But he spoke in a way that wounded pride...He didn't need to speak in that way.”

But in his cave of books, al-Sharbinder remains unflappable. He has lived through decades of upheaval and al-Mashzoub’s death has not shaken him.

“Of course, some people are afraid, some flee,” he says, “But the old thinkers face death with strength.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.