Break down the castle door: Turning the lens on a legendary Syrian filmmaker

In an extreme close up, film director Nezar Andary is holding the frame of a door handle against his forehead, squinting into its keyhole as if it were a viewfinder and turning it like a focus dial on a camera.

At the same time we hear Umm Kulthum’s voice singing in an unusually high register a spellbinding tune: “The eye is precious, the heart is dear, / And they don’t like what love has done to me.”

It is the opening scene of Unlocking Doors of Cinema: Mohamed Malas and the only time Andary appears in the film, whose subject is the 74-year-old Syrian filmmaker.

Umm Kulthum's 1928 song is an early example of the aria-like “monologue” form in which, rather than returning to a melodic refrain - as in a traditional Arab song - the tune progresses freely from one melody to another.

Lifted from Malas's second feature, The Night (1992), you might expect its lovesick slowness to induce nostalgia or melancholy, but together with Andary’s Duchampian snippet of physical theatre, it has a rousing effect.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Less than a minute since the start of the screening, and Unlocking Doors has already made a crucial point: that this is what cinema does. It uplifts, it transports, it provokes wonder. It remakes the past using raw materials from the present, enabling you – viewer, subject, or indeed filmmaker – to become someone new without having to disown a previous version of yourself.

By the time the final credits roll exactly an hour later, you will have no doubt that, in this sense, Malas is the perfect cinematic subject. He is a shapeshifter.

Everything Is Alright Mr Police Officer

Based on 16 hours of interviews with Malas, Unlocking Doors started out as a short documentary project to accompany a book Andary, an associate professor at Zayed University in the United Arab Emirates, was writing with fellow film scholar Samira Alkassim. But the project went so well he felt he had enough material for an hour-long feature.

Much of his work dealt with the Arab-Israeli conflict and the plight of the poor and the dispossessed

Few would dispute Andary’s conviction that Malas is one of the most important filmmakers living and working in the Arab world today. Together with that of the late documentary filmmaker Omar Amiralay (1944-2011), Malas’s filmography, comparatively short as it remains, has come to define contemporary Syrian cinema for the world at large.

Unlocking Doors is deceptively straightforward, with Malas’s talking head spliced with scenes from his films or footage reflecting episodes from his life organised around white-on-black titles. But it is cut in such a way that it ends up mimicking the expressive, non-linear style of Malas’s own films.

Andary subtly emphasises the poetry and the irony in what remains, on the surface, essentially an extended interview, albeit one that avoids any explicit discussion of politics, ideology, or the political-ideological obstacles that have prevented Syrian filmmakers from producing the work of which they dream.

Malas is associated with the Arab left not only because he studied in the Soviet Union but also because much of his work dealt with the Arab-Israeli conflict and the plight of the poor and the dispossessed.

In 1980-1 Malas spent months filming Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. He asked them not about their political convictions or memories of home but about what they saw in their sleep. But, because some of the friends he made at that time were killed in the Sabra and Shatila massacres a year later, which forced him to stop working on the project, The Dream was not released until 1988.

As a film student in Soviet Moscow, Malas shared a room with the Egyptian novelist and life-long dissident Sonalla Ibrahim, whose epoch-making novella That Smell he mentions to Andary. Malas cast Ibrahim – a former political prisoner in Egypt – as the lead in his graduation project, Everything Is Alright Mr Police Officer (1970), which is set inside an Arab prison.

Like Ibrahim and many others, he admired the Egyptian leader and national liberation champion Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918-1970) for nationalizing the Suez Canal in 1956 and starting the 1958-1961 union with Syria, which gives his celebrated Dreams of the City (1984) its hopeful ending in which the full gamut of characters who have appeared in the film are seen celebrating Nasser’s visit to Damascus and the union between Egypt and Syria.

Dreams and Destiny

Malas depicts his own childhood in Dreams of the City, the film most often cited in connection with him. Even though he didn’t make it until he was nearly 40, Dreams is Malas’s debut narrative feature, and one of the earliest examples of auteur cinema in the Arab world.

A poetically veiled autobiography set between 1953 and 1958 in Damascus, it recounts how the pre-adolescent carpenter’s son from from the now deserted Golan Heights city of Quneitra, Israel’s destruction of which Malas had documented in Quneitra 74, leaves with his mother and brother after his father’s death and, while working at a dry cleaner’s to help with his small family’s expenses, discovers political life through conversations, fights and demonstrations he witnesses on the street.

In his friend the late Youssef Chahine’s feature film Destiny (1997), set in 12th century Cordoba and shot at locations he helped select all across Syria, Malas appears as medieval Andalusian gentleman. The cameo would be insignificant if not for what it meant to him.

A potentially deadly accident a few months before in Damascus had affected his vision, making him see double and disturbing his sense of space, and this left him less excited about cinema, and less eager to make films, than he had ever been.

When Chahine refused to start shooting Destiny until Malas agreed to act in it – acting was something he neither did nor wanted to do – the latter did not realise that his friend’s intention was to “bring the warmth of cinema back into him”, as he put it.

“Maybe even after I die,” Malas tells Andary in the documentary, “I will not forget this.”

Questioning beliefs

But there is a deeper level of shape shifting, too. In cinema that seems to celebrate it, Malas throws Arab nationalism into doubt. He questions his deepest beliefs.

Towards the end of Dreams of the City, Deeb is seen running after the man who, on the pretext of marrying his mother, tried to take advantage of her. With a pair of scissors hidden in his coat, the boy trails that false suitor until he comes up against a locked barn door.

Through a chink, the fugitive’s indistinct figure can be seen climbing some steps past the animals at the far end while, desperate to break in, the would-be avenger kicks, butts and bangs his head on the wood till he is knocked out.

However subtly, with this image, Malas presents a powerful revisionist metaphor for the whole Arab nationalist project. The boy splayed out in the dust, having failed to take his revenge, evokes not the 1958 union which “even God apparently supports”, as one adult character tells Deeb at the end, but the defeat of Nasserist Egypt and Baathist Syria in the 1967 June War.

As fledgling postcolonial states committed to the Palestinian issue, the two countries had a just cause and a sound aspiration to prosperous independence. But beyond brute patriarchal force – a force embodied in the stinginess and cruelty of Deeb’s maternal grandfather – they had no way of articulating either. Moral certainty made them impotent, the film implies, and so they ended up hurting their own citizens more than the enemy.

Banging on the door

Mimicking his diminutive alter ego some 36 years later, at the tail end of the section dedicated to Dreams of the City in Andary’s film, the 74-year-old auteur is seen kicking, butting and banging his head on a wooden door.

'Even though his work reflects an existential melancholia, he is not a victim of the maps of colonialism, corrupt Arab nation-states, Israeli intransigence, or nationalism'

- Nezar Andary

It is one of many doors in Talhouk Castle, the spacious and varied property of the Makarem family in Aitat, Mount Lebanon, where the Sami Makarem Cultural Centre provided Andary and his Damascus-based subject with a safe haven for their audiovisual encounter.

This time the reference is not to the failure of Arab nationalism so much as the economic and political obstacles facing Syrian filmmaking since the seventies. That is what the conversation is about at this point in the documentary.

And, unlike the barn door, this one tellingly does open to let Malas past, suggesting that, all things considered, the determined director has triumphed against those obstacles in the end. Desperation, Andary is saying, doesn’t have to imply despair.

“The films, writings, and life of Mohamad Malas are a testament to the heroism of persistence and expression,” Andary tells me via email.

“Even though his work reflects an existential melancholia, he is not a victim of the maps of colonialism, corrupt Arab nation-states, Israeli intransigence, or nationalism," he goes on. "This feature documentary develops an understanding of his achievements as an intellectual from a country that has become a metaphor for war, refugees, and geopolitical conflict.”

Even in his last film, Ladder to Damascus (2013), made at the risk of arrest or being caught up in the violence during the Syrian revolution, the act of filming is bound up with both love and protest.

The film demonstrates how the powers that be not only crush dissent but also youth, secularism and the creative impulse. At the same time, by turning the camera into a tool for political activism, the revolution validates not only Malas’s career but his existence as a filmmaker who is also an engaged Arab citizen eager to participate in the progress and development of his society.

“What has happened in Syria is a disaster beyond comprehension,” Andary said, “but it is not a simple theoretical or aesthetic construct. The mere mention of Syria and an understanding of its present status are starting points that require a cinematic and humanist approach to contextualize historical and cultural realities.

"To search for truth between the cinema of the past and the values that Malas creates in each films allows me to question things much more.”

Breaking the fourth wall

Even at the most realistic moments, the Russian-trained, Tarkovsky-influenced Malas has his actors move in slow and stylised ways. But unlike Bassel Abiad, the young man who plays Deeb, when he bangs his head on the Talhouk Castle door in Andary’s documentary, Malas makes no attempt at hiding the fact that he is playacting.

Celebrating the artifice inherent to the act of filming is something he and Andary do throughout Unlocking Doors. What in another film would be bloopers or out-takes are worked into the fabric of an iron-tight final edit.

In Andary’s documentary, the spritely figure with a white mane not only switches between formal and colloquial Arabic and between set and spontaneous poses, he also experiments with different choreographic sequences and discusses directorial decisions with Andary, sometimes even telling him what to do.

And of all the essential things this movie does, breaking the fourth wall in this way may be the most essential in that it shows how creative filming can turn a potentially dry or even demagogical, factual conversation into a stimulating aesthetic experience.

Andary sets out to summarise the filmmaker’s life and work – which he does. But his major achievement is that, in talking about cinema, he makes cinema speak about itself. This is the sense in which presenting an alternate view of the beloved country, telling a different story of Syria and the whole Arab world, is most valid.

Superimposing Malas’s films and other, relevant footage onto the conversation at the heart of the documentary, Andary teases the art and humanity out of the nightmare of history. But in the process, he also recounts that nightmare.

The film ends, as it begins, with sound, specifically the sound of Malas’s voice echoing, “Like this, like this”, while his figure fades to black.

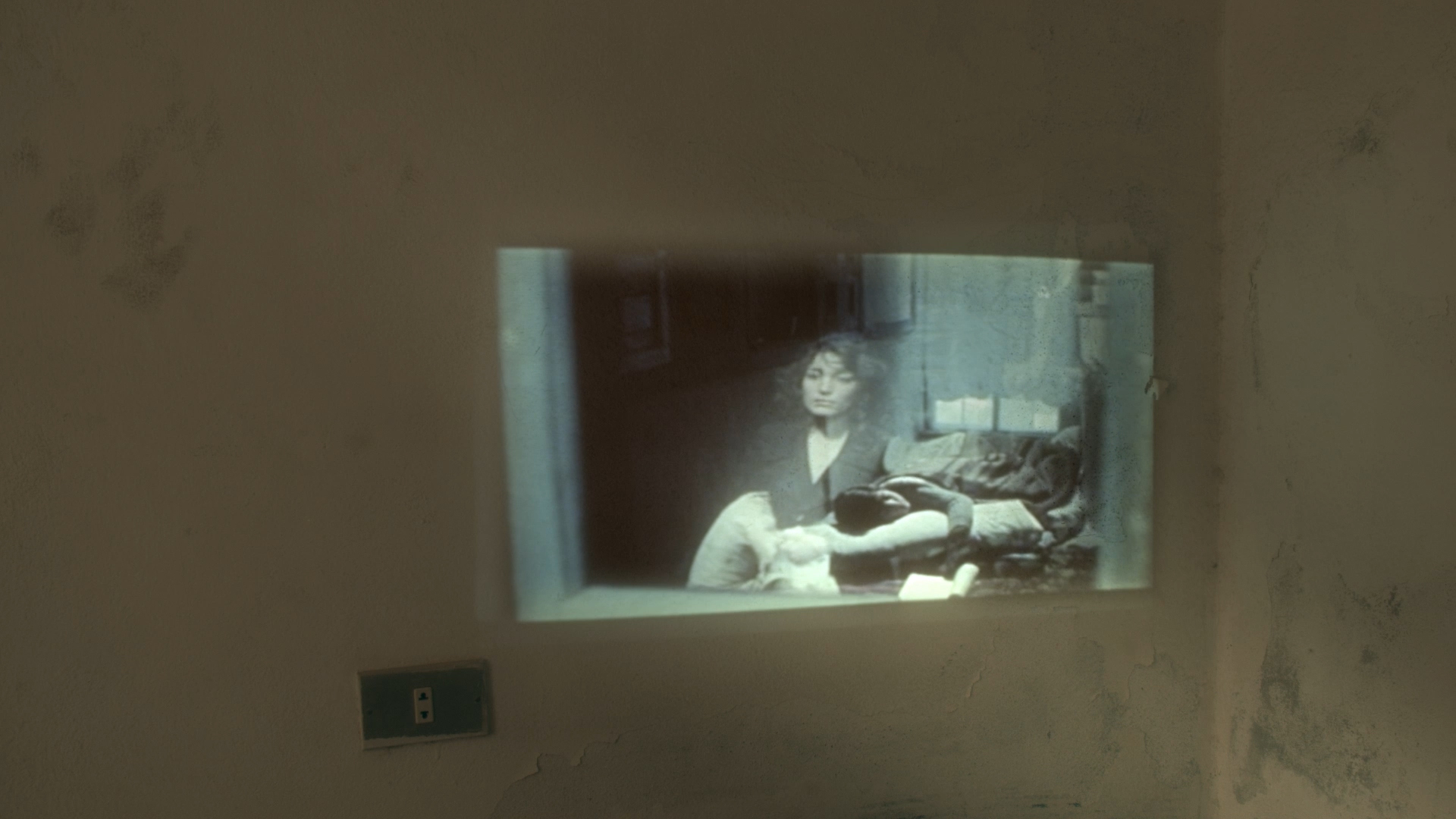

But, though it occurs early in the film, it is the sight of his unmoving face mid-frame while his work is being projected on the wall to one side – a kind of animated icon to which the Arab cinephile might pray – is perhaps one of the most memorable images in film this reviewer has seen.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.