Midnight in Cairo: The glitz, glamour and grit of Egypt’s leading ladies

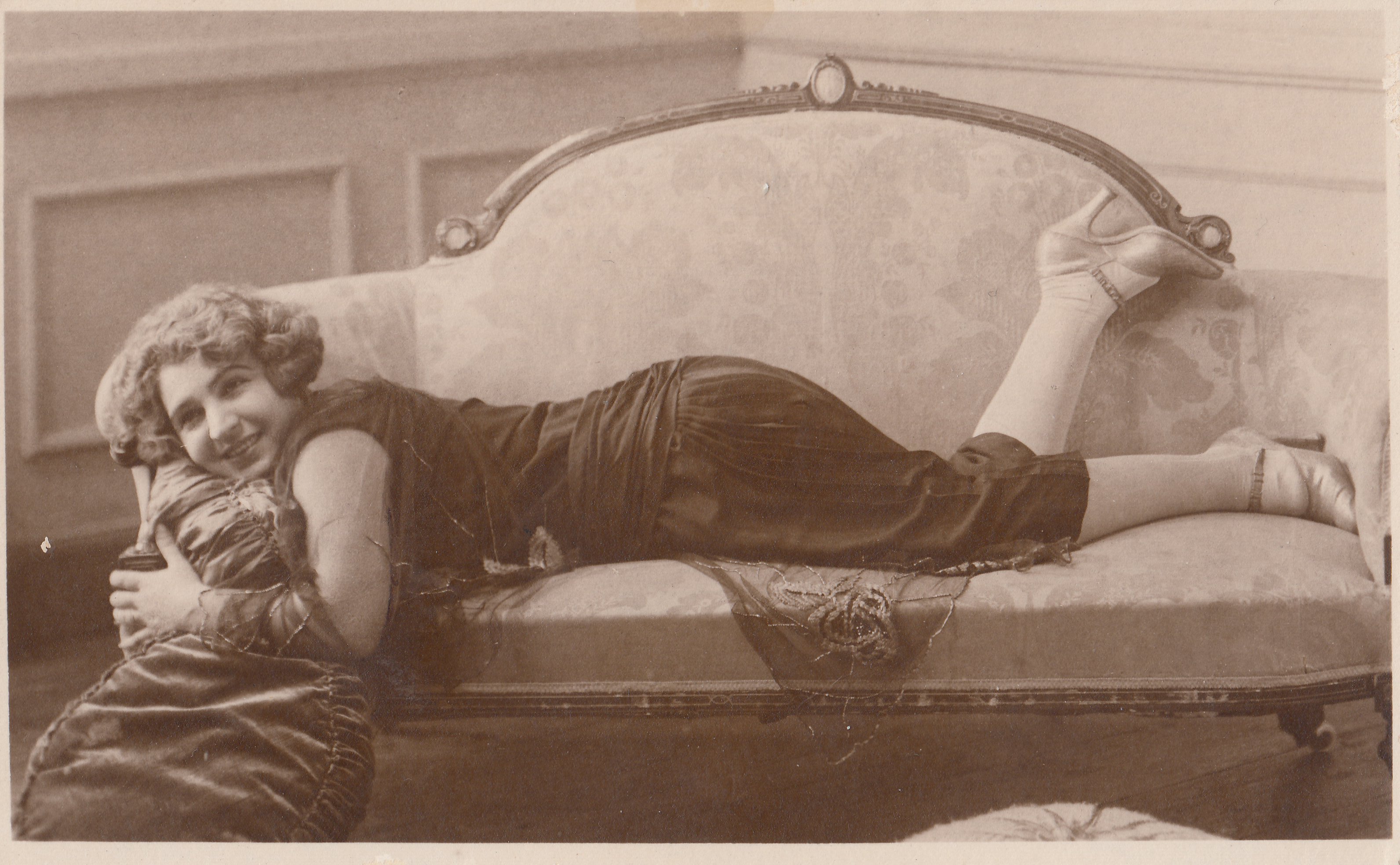

Chandelier dancer and music hall owner; cross-dressing singer and troupe leader; vaudeville actress and media magnate: these are the main characters of Midnight in Cairo: The Divas of Egypt’s Roaring '20s, a new book by Raphael Cormack, which profiles seven remarkable women of Egypt’s nightlife and entertainment industry.

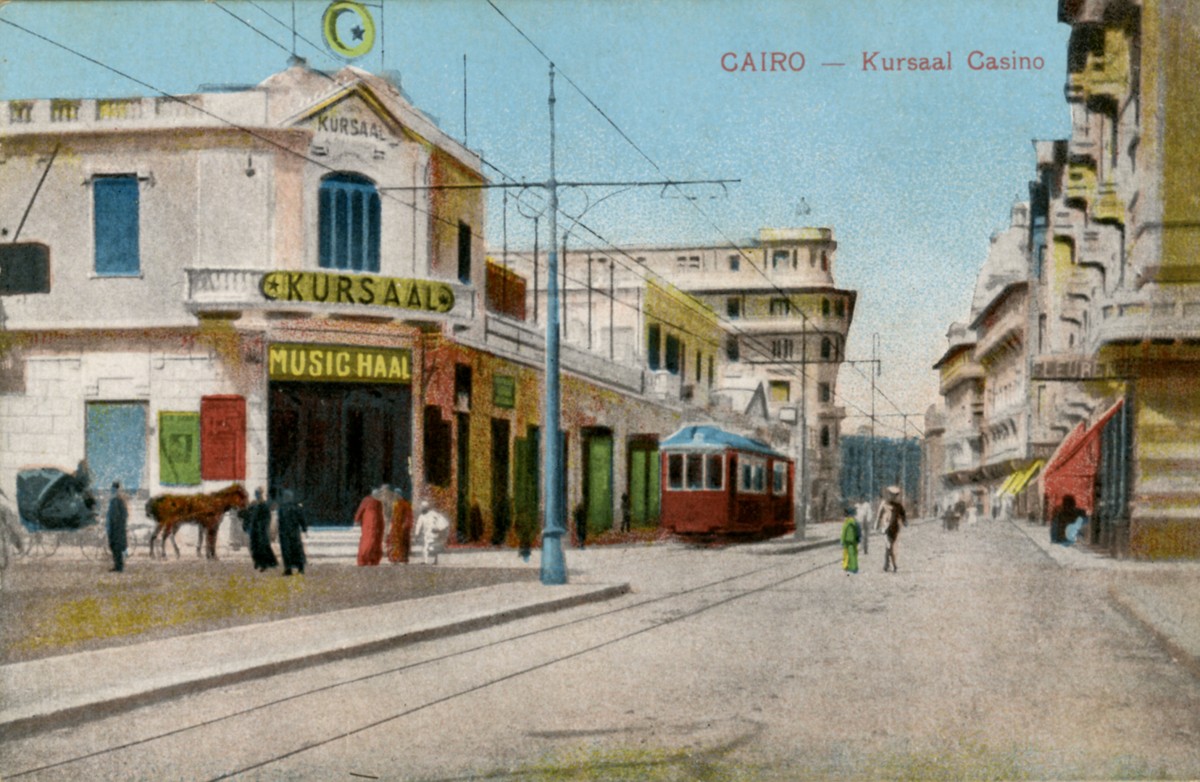

Together, these actresses, singers, theatre troupe leaders, and cabaret owners tell the story of a heady downtown Cairo, rife with the promise, cosmopolitanism, and party scene of the ‘20s and ‘30s. Today, many of the district’s bars and coffee shops, the wide avenues and statued squares designed to emulate European capitals still stand, give or take a century and a few cycles of revolution and gentrification.

But walking through the busy area after my conversation with Cormack, I’m struck anew by how the district barely hides its gilded past. Under a thin veneer lies the withered but surviving image of downtown Cairo, where young intellectuals became nationbuilders and the vestiges of empire faced off with early feminists in a rapidly modernising social scene.

“I think anyone who knows downtown Cairo knows there’s a real sense of history there - even though a hundred years isn’t old in comparison to most of Egypt’s history. I wanted to write a book that captured what it might have been like, a hundred years ago, to be downtown, in the entertainment business,” says Cormack, who lived in the area when he was working towards his PhD in 2017 and found himself immersed in literature about the era.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Interwar Egypt is the backdrop for an oft-mythologised cosmopolitan Cairo, where African American jazz musicians, British colonial officers, wandering intellectuals, and political agitators mingled in the red-light district

Part of the book’s charm, admittedly, is in a kind of nostalgic reality TV: the scandals, affairs, marriages, divorces, and hilarities that surrounded not just the first modern Egyptian celebrities, but a country at a crossroads.

Interwar Egypt - technically independent but functionally occupied - is the backdrop for an oft-mythologised cosmopolitan Cairo, where African American jazz musicians, British colonial officers, wandering intellectuals, and political agitators mingled in the red-light district.

More than anything, one central truth jumps out about the book: it is absolutely, hilariously, delightfully wild. Start to finish, the 300-page book is an easy, riotous read.

The book itself leans into the world’s theatricality, in both prose and structure. In addition to chapter titles like “Pardon Me, I’m Drunk” and “Come on, Tough Guy, Play the Game”, Midnight in Cairo is organised into three acts of a play, each relating to a different historical era.

Cormack isn’t shy about taking readers on wonderfully wild cul de sacs, little tangents where we get to meet people like the Iraqi-Palestinian mystic who was allegedly expelled from Egypt for sleeping with a royal and the opera composer whose only company was his fruit-eating cat, Farfura.

The result is a vividly populated world of entertainment and drama, aided by Cormack’s attention to bringing to life the spaces, sounds, and smells of golden-age Ezbekiyya district, (the centre of Cairo’s nightlife, adjacent to downtown Cairo today), a map of which starts the book.

No ‘respectable’ feminists

The book’s cast of leading ladies is a remarkable collection. Some, like singer Fatima Sirri, serve to illuminate a particular aspect of life as a woman and entertainer. Featured in the book for arguably her most enduring legacy, Sirri dragged Mohamed Shaarawi, son of feminist icon Huda Shaarawi, to court in 1925 because he refused to recognise their child. Her legal battle, which lasted until 1931, would provide the blueprint for decades of paternity cases to come.

Many others, however, including Om Kalthoum, Mounira al-Mahdiyya, and Badia Masabni, have legacies so enduring as superstars and pioneers of the entertainment industry that they couldn’t have been omitted. As a result, readers familiar with Egyptian culture will hardly experience Cormack’s rendition of these women’s stories as “returning them to the limelight after almost a century,” as the introduction reads.

Even knowing Om Kalthoum's story, I personally enjoyed seeing her in conversation with the other celebrities of the time, as both divas and decision-makers. For instance, she and her rival - the less famous but no less influential actress and singer Mounira al-Mahdiyya - were brilliant publicists, curating impeccable (and opposite) public personas.

While Om Kalthoum leveraged her image as a sheikh’s daughter to brand herself as moral and demure, perfectly in line with traditional sensibilities, Mounira al-Mahdiyya was openly transgressive, curating a thrilling persona based on rumours she often started or fed herself.

Cabaret owner and performer Badia Masabni was a resolutely independent entrepreneur, and her cabarets are still remembered for giving some of the biggest stars of the 20th century their big breaks, including famed dancers Tahiya Carioca and Samia Gamal, and singer Laila Mourad.

Rose al-Youssef went from poverty to vaudeville actress to media founder, and Aziza Amir’s proto-feminist filmmaking produced the first Egyptian film. Her silent village drama Laila premiered in 1927, nine years before Studio Misr - hailed as the first Egyptian-owned and funded cinema studio, helmed by pioneer entrepreneur Talaat Harb - released its first film Wedad in 1936, starring Om Kalthoum.

These are impressive stories, without a doubt. But it’s also thrilling to realise that these aren’t the classic stories of early 20th century Egyptian feminists, the likes of Huda Shaarawi and Safiya Zaghloul. Though they lived at the same time and led intersecting lives, the conventional story of well-connected, highly educated Egyptian feminists doesn’t have room for the singers, dancers and actresses of the burgeoning nightlife scene.

“They lived in the margins of so-called decency, and hardly anyone who saw themselves as respectable wanted to be publicly associated with them,” as Cormack writes.

Not only did they inhabit the unseemly world of the nightlife district (stigmatised as a moral and literal stone’s throw away from Ezbekkiya’s red-light district), these women also came from poverty and were often uneducated - only learning to read in order to rehearse (and pioneer) Egyptian theatre - a far cry from bourgeois feminism.

“You have these women of the stage, who had sort of given up a little bit of their respectability, but can make these much stronger demands,” Cormack tells MEE. “They made their own money, which allowed them to take more risks, because they had something to fall back on. Mounira al-Mahdiyya, for example, could divorce her husband, as well as pay him off.”

Who to Party with, Who to Meet

Cormack isn’t exactly shy about playing favourites. Already suspecting the answer, I ask him who, of the cast of women, he would meet if he could only choose one. The first name he says is al-Mahdiyya.

Sultanat al-Tarab - The Queen of Musical Rapture, as she was known - the singer and actress is credited as the first woman to lead her own theatrical troupe, the first Egyptian Muslim woman to act on stage, and the inventor of Arabic opera. The sultana was also fascinatingly transgressive. A frequent crossdresser both on and offstage, she would feed the press photos and rumours, throw lavish parties at her houseboat, and keep an illustrious court of politicians. One of the rumours her lifestyle spawned - fanned by Mounira herself - was that Egypt's parliament once held a session on her houseboat.

“The way she constructs her celebrity persona is incredible,” Cormack says. “Slightly bad girl, playing poker on her houseboat with politicians, a little bit demi-monde and fun, always coming up with some wild story about herself. She remains, for me, the most interesting one to study. But I’m not sure she’d the best one to meet…the best person to go to a party at her house, though, for sure.”

The answer we settle on, in the end, is to party on Mounira al-Mahdiyya’s houseboat, but meet Shafiqa al-Qibtiyya. The queen of the 1890s music halls of Ezbekiyya, Shafiqa is remembered for her gravity-defying dancing (she’s credited for inventing the iconic candelabra dance), running her own dance hall, possessing obscene wealth, and seducing the elite.

With her career-ending in the 1910s, around the time the entertainment press was first gaining steam, her life remained shrouded in mystery. She was only mythologised in retrospect, including in a 1963 film starring silver screen darling Hend Rostom.

Mythologising the nightlife and entertainment scene didn’t end with the rise of the press in the 1910s; it was fuelled by it.

As a result of decades of gossip columnists, generations of rewriting history, and quite an oeuvre of sensationalist memoirs, Cairo in the '20s and '30s occupies a very particular place in the cultural imaginary: a nostalgia for a glamorous era that often, as nostalgia does, obscures the very real violence of the time.

It would have been possible - and likely still made for quite a compelling book - for Cormack to simply revise the narrative of a romantic, whitewashed cosmopolitanism, rework it to feature the leading women in all their agency, but stop short of real critical engagement. Instead, Cormack teases out important contradictions that aren’t always present in depictions of interwar Egypt: “a scene that was enticing and seductive but also exploitative and dangerous,” as he writes.

Cormack ultimately succeeds in depicting an intentionally balanced view: these women were entrepreneurial forces, but had to carve their way amid disparagement, prejudice, and violence. They had fabulous affairs and illustrious marriages, but their vulnerable positions made way for disgustingly predatory relationships as well. Interwar Egypt was a place of colonial control, poverty, and inequality, in addition to a site of dazzling promise.

Reading Yesterday Today

As an Egyptian woman and culture writer, reading Midnight in Cairo felt like reading my own history. It had me laughing in recognition at the cabarets of old, that I only know today for hosting raves. It had me annotating expletives in the margins as I read about Rose al-Youssef’s hilarious face-off with Talaat Harb on an Alexandria beach.

And it had me rolling my eyes at how some things never change. The first theatre troupes of the late 19th century, for example, featured comic stock characters like “the hashish-addled servant, the foreigner out of his or her depth, and the upper-crust Egyptian who tries, with comic incompetence, to ape European culture” - three tropes that consumers of modern Egyptian comedy can recognise as having never really faded.

It perhaps shouldn’t have been as surprising to see that the discourse around women in culture also hasn’t changed much. Cormack lists cases of conservative critics calling on the government to enforce stricter censorship on women’s performances, female dancers subjected to legal action in addition to moral condemnation, and misogynist anxiety of “fevers that have almost totally destroyed our morals”, invariably targeting women.

In its fullest expression, like the murder of dancer Imtithal Fawzy in her own club in 1936, this makes for quite difficult reading. In spite of myself, I met these sections with bated breath, waiting for Cormack to trace the obvious line to today - for instance the arrest of TikTok influencers and belly dancers in defence of “public morality” - an overt connection that never came.

In explaining his process of writing these stories of Egyptian women as a western man, Cormack also tells me that he wasn’t sure his decision to leave those connections up to the reader was the right choice. I think it was. For once, I found myself relieved to not find the struggles of Egyptian women weaponised either for or against me.

Cormack’s prose is compelling and entertaining, peppered with details, anecdotes, and perspectives even students of Egyptian history are unlikely to know

Cormack approaches the lives of Egyptian women in the golden age of entertainment and nightlife with humour, balance and reverence. Though he is intentionally adding a light-heartedness to the “Middle East” sections of British and American bookstores, he also makes room for the ambivalent reality of these women’s worlds, while not attempting to draw larger metanarratives.

Also as a result of Cormack’s intention to aim the book at both western and Egyptian audiences, it is a curiously different book depending on who reads it. For unfamiliar readers in the UK and the US, where it is published by two different presses - Saqi and W. W. Norton - it is a fascinating immersive introduction into a new world.

Readers in or from Egypt (where it is published by AUC Press) - as well as those those familiar with Arab culture - will be at least tangentially familiar with the characters. But at no point does this familiarity breed tedium. Cormack’s prose is compelling and entertaining, peppered with details, anecdotes, and perspectives even students of Egyptian history are unlikely to know, aggregating stories in fresh ways.

Case in point: you might be familiar with the political details of the 1919 Revolution of Saad Zaghloul, but less so the delightfully absurd visual of theatre troupes organising carnivalesque marches in full Shakespearian and Abbasid regalia, chanting against the British while dressed as Othello and Haroun al-Rashid, all while composing anthems that would survive as emblems of Egyptian patriotism, all the way to Tahrir Square in 2011.

At heart, Midnight in Cairo is the story of women who built their own careers, made their own money, and told their own stories. It is a fascinating, refreshingly authentic work that cleverly walks the line of portraying a "golden age" of glitz and glamour, drama and hilarity, while faithfully representing an imperfect time period, full of as much danger as promise.

Midnight in Cairo is out now from W. W. Norton in the US, expected in the UK from Saqi Books and Egypt from AUC Press.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.