Arab idol: The rebel singer who blazed a trail

In the grainy black and white video, singer and actress Taroub glides across to centre stage and dances seductively to the intro of "Ya Sitti Ya Khityara" (Oh My Old Grandmother).

The year is 1974 and she’s performing on a New Year’s Eve broadcast on Lebanese TV. Wearing a low-cut backless sequined top and long skirt, she twists her hips back and forth and spins full circle, singing an Arabic-language version of the distinctive Spanish melody El Porompompero.

In the backdrop, a rotating spiral forms a psychedelic halo behind her head as she sings to her grandmother about her lover:

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"Should I wear my yellow dress or my red dress.

He is taking me out tonight.

Tell us where we should spend the night?’"

When the Syrian-born singer recorded the song, just a year before Lebanon’s civil war broke out, she was at the height of her career within the country’s vibrant 1960s and 1970s music scene. Her playful lyrics, daring dress sense and bold stage presence shaped her identity as a modern pop artist willing to push social boundaries.

“Taroub clearly pushed the boundaries at the time. That was one of the keys to her success,” says Sami Asmar, an Arab music analyst and writer based in Los Angeles.

Although Taroub was emblematic of a certain freedom that existed in Lebanon at the time, she also raised numerous eyebrows in a country that was still adjusting to the changes that came with modernity.

It’s rarely acknowledged, but Taroub composed many of her own melodies, including her most well-known hits. Within a patriarchal music scene where women were predominantly the vocalists, and men their composers, lyricists and producers, she was a true pioneer.

Early career

Taroub, who was born Amal Ismail Jarkas in Damascus in the late 1930s and grew up in Amman, first rose to regional fame during the late 1950s as part of the Arab world’s most popular duo with her then husband, the Lebanese composer and singer Mohammad Jamal. They were simply known as Jamal and Taroub.

“In the 1960s, Jamal and myself were performing everywhere,” she says – from a cafe in Verdun, an upper-class residential district of Beirut. “Wherever we visited, we were the talk of the town.”

Now in her early 80s and retired from music for more than 20 years, Taroub is in Lebanon for a short visit from Cairo, where she’s lived since 1976. She sits in a leather armchair, wearing flower-shaped diamond earrings and a NY sports cap over her veil, her eyes framed with kohl.

“I always speak the truth,” she says. “Me and Jamal were not the first duo. There was another before us called Dia and Nader in Egypt. But slowly, after a year or so, we built our name and became number one.”

Taroub is from a Circassian family, her father Jordanian and her mother Syrian-Turkish. She started her career as part of the choir of Radio Damascus during the 1950s, then moved to Lebanon in 1956, where she was hired to work at national Lebanese radio.

At the time the station was a cornerstone of the blossoming music industry: here, composers such as Halim El Roumi and George Yazbek recorded with new singers, while label owners scouted for talent.

Taroub was hired to sing in Beirut’s Mansour Restaurant where she met Jamal – they fell in love, got married and formed an artistic duo,

Active between 1957 and 1964, the young charismatic Jamal and Taroub soon became stars for their fresh approach to pop. Backed by an orchestra, they toured the theatres, restaurants and cabarets of the Arab world, participating in the prestigious Adwaa’ Al Madina concerts in Cairo, organised to celebrate the new United Arab Republic that unified Egypt and Syria between 1958 and 1961.

With their performance broadcast live on the republic’s new TV channel, the couple’s popularity soared overnight and they moved to Cairo, the centre of gravity for Arab music at the time.

Going solo

But only a few years later though, Jamal and Taroub divorced - their musical partnership ended and she returned to Lebanon to pursue her solo career.

“While we were together, Jamal wrote everything,” says the singer, stirring sugar into her Nescafe.

“We were known as Jamal and Taroub, and then all of a sudden it’s Taroub on her own.

“When a duo splits there will always be crackles afterwards, but I struggled on until I proved myself.”

Jamal and Taroub achieved huge popularity as a duo, but it’s the modern pop songs Taroub released as a solo artist, from the mid 1960s to the mid 1970s, that are remembered today.

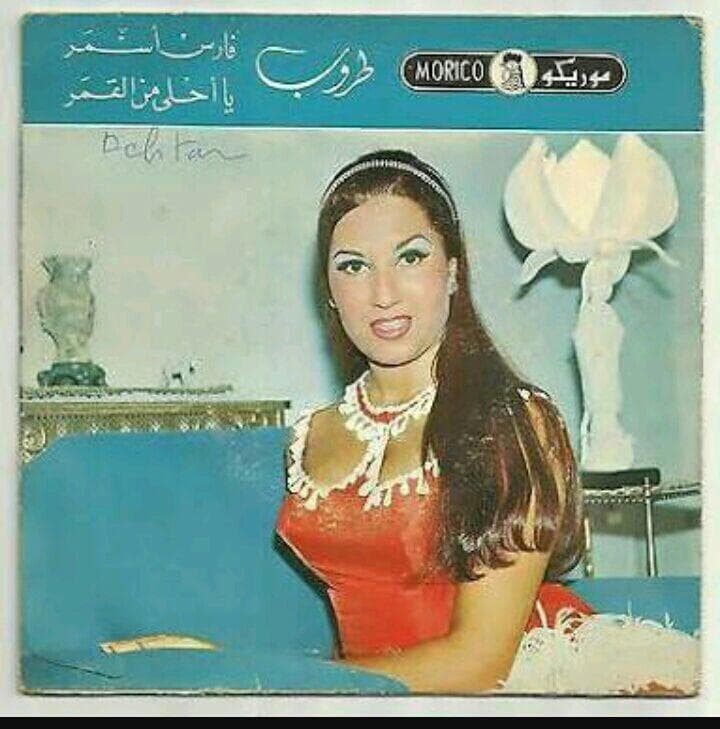

With her kitschy records about the simple pleasures of modern life – boyfriends, love, staying out all night – she heralded in a wave of Lebanese music that was fun, light-hearted and carefree.

Soon Taroub began to write her own compositions, drawing on her Turkish and Middle Eastern roots for influence. Unable to read music, she would record melodies on a cassette recorder, then give them to a musician to transcribe.

One of her first solo songs featured her composition "Abu Zeid Al Hilali" on the A-side and Jamal’s "Khayr Yawm" (Good Day) - one of his last compositions for her - on the reverse.

Taroub lists some of the biggest composers she’s collaborated with - Farid El Atrache, Mounir Mourad, Mohammad El Mougy and Sayed Mekkawi. She pauses.

“I am the biggest,” she says, followed by a wild laugh. “I was the only female artist from my generation that composed music – they never mentioned this.”

Flicking through a collection of her vinyl singles in the café, a ray of sunlight hitting the tiled floor by her feet, Taroub pulls out the melodies she wrote in her mid-60s to 70s heyday: her hit "Ya Hilaq" (Oh Barber), "Dawwya Ya Qanadil" ('Light Up Oh Lantern'), "Al Wald Wld" ('A Boy Remains a Boy') and "Aman Doktor", also known as "Ya Sababin Al Chai" (Tea Pourers), which the Egyptian composer Baligh Hamdi once complimented her on.

Taroub also wrote melodies for the Lebanese singer Jacqueline, along with her own sister Mayada, who had a small but interesting career during the 1960s, singing pop with a rock and roll twist.

'I was the only female artist from my generation that composed music – they never mentioned this'

- Taroub

“Taroub should be credited immensely for this contribution,” says Sami Asmar. “I can’t think of any women from that era who composed song material. It was more than unusual, probably unheard of.”

Within a competitive music scene of strong female artists, Taroub was able to create her own strand of Lebanese pop. Her music was a melting pot of influences, mostly blending Turkish, Arabic and European melodies.

She often mixed Arabic, Turkish and English lyrics, as in "Come to Alexandria", an Anglo-Arab song she released with Karim Shukri, or her cover of Bob Azzam’s "Ya Mostafa".

Taroub’s international sound fitted perfectly into cosmopolitan Beirut, a global destination of leisure from the 1950s to the mid 1970s with its diverse music and nightlife scene.

“Back then, Lebanon was at the peak,” she says. “There was a beautiful artistic life, especially in the summer. It was called the season of the mountains and every restaurant and club was packed every day.

“I played outdoor concerts at the Grand Sawfar Hotel, Piscine Aley and Hammana.’

At venues across central Beirut, house bands played everything from jazz and bossa nova to schlager (the europop of its day), rock and roll and twist.

This multitude of influences can be heard on many records of the period, including Elias Rahbani’s Franco-Arab releases and the Armenian singer Adiss Harmandyan's estradayin style, a genre of Armenian diaspora pop music.

‘There was and still is tremendous influence from neighbouring cultures in Lebanon’s music scene and European in particular was fashionable,” says Asmar. “Taroub knew how to draw on this successfully, but when you hear a Taroub song, you still think it’s a Lebanese song. She melted her work into Lebanese pop material.”

Movie career

Taroub also had a sizeable cinema career, starring in more than 20 films from the early 1960 to the 1970s, mixing Arab and Turkish productions.

“Taroub mostly acted in comedies, espionage and sexploitation movies,” says film archivist Abboudi Abou Jaoude, who has an extensive archive of cinema posters and memorabilia from the Arab world’s golden age of film production. “She often played the sexy figure or main love interest.”

Her film career exploded during the mid-1960s when she appeared in Lebanese films like Al Jaguar Al Saouda by renowned director Mohamed Salman and co-starred in the 1965 film Al Bank with her sister Mayada.

Her ability to speak Turkish meant she co-starred with the likes of Sabah, Farid Shawqi and Ismail Yassin in multiple Arabic-Turkish co-productions – a common cost-cutting practice at the time where two films were produced from one shoot, then edited and dubbed differently for each region.

Controversy

Performance was also central to Taroub’s pop artist persona. She was one of the first singers to break free from the static Oum Kalthoum stance behind the mic, and move while singing. Dancing itself was a rebellion of sorts, particularly within her own conservative family.

“Dancing always attracted me, but I knew that my mother will absolutely not allow me to dance,” she wrote in a 1959 article in Al Kawakib Magazine.

Taroub also made some of the region’s earliest video clips – smoothly choreographed performances of her songs, filmed in Lebanon and Syria, decades before the Rotana TV generation moved in.

In a late 1970s video of "Ya Sitti Ya Khetyara", Taroub dances in a flamboyant pink dress, backed by a group of male flamenco dancers.

Filmed in Egypt, the clip was part of a one-and a-half-hour-long TV show, broadcast across the Arab World, called A Night With Taroub – the singer paid for and produced it herself. In another she commands the stage, elegantly swaying to the rhythm of "Tikki Tikki Tak".

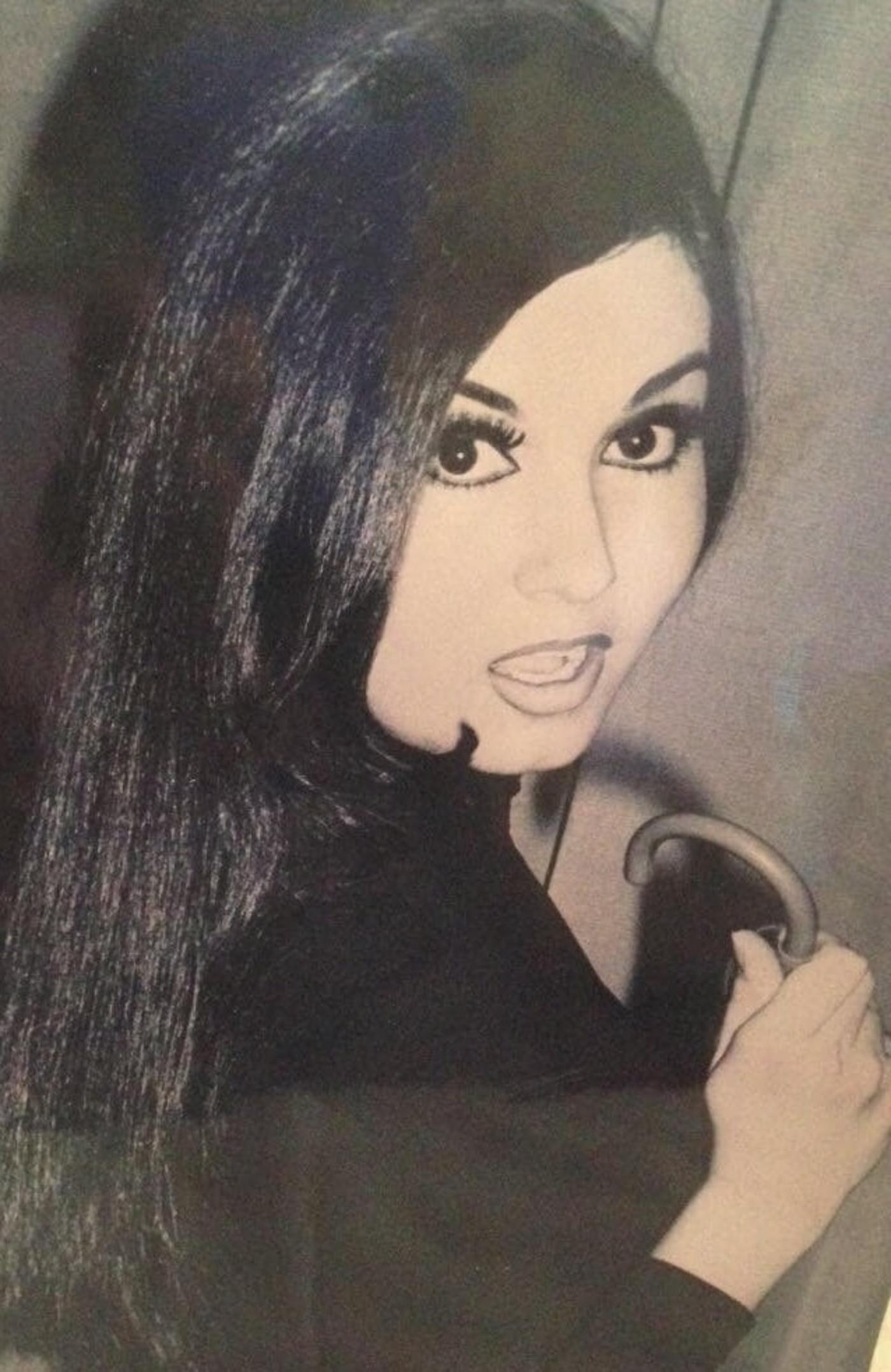

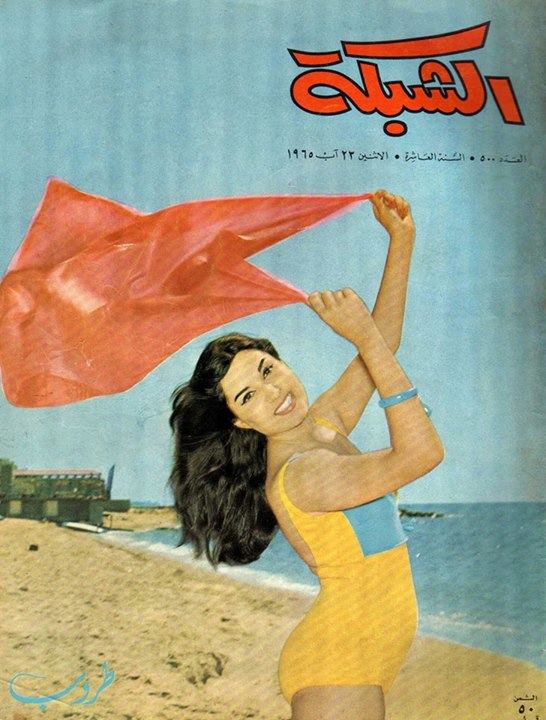

During the mid 1960s, Taroub was a cover star of popular arts magazines such as Al Funun and Al Chabaka. Pin-up style portraits of her appeared on the sleeves of her releases, dressed in the latest fashions.

“It was not just my singing style, even the way I dressed was very bold,” says Taroub. “Many journalists criticised me. They used to say ‘Taroub is singing with her legs.’ I’ll never forgot when they wrote that in the newspaper. But I didn’t care.”

Although Taroub fully embraced the new freedoms of a society in transition, there were many resisting change. “My family are all Circassian – for them singing is a shameful thing. I couldn’t go to Jordan for years,” she says, adding that her uncle threatened to shoot her if she returned.

When she was married to Jamal, Taroub’s father-in-law took issue when paparazzi photos of her wearing a bathing suit on a beach in Alexandria appeared in an Egyptian magazine. As a result, she was said to have been forced to move her swimming sessions to a ladies-only club while Jamal waited outside.

Asmar recalls: “She wore short skirts on TV, and I remember my own mum being shocked but wouldn’t change the channel. She and the family and friends would giggle when she sang daring lyrics. They would actually say: 'She’s not Fairouz, but she sure is cute.' With that, she broke some walls and allowed others to follow.”

Musical revival

More than 40 years have passed since the peak of Taroub’s career – but her music hasn’t lost its charm. Today her songs have found a second life among a new generation, part of a wave of interest in the Arab world’s musical heritage.

Her records are now spun in a modern clubbing context, danced to by a new generation at the Beirut Groove Collective (BGC), an all-vinyl club night on the roof of an old kitchen pot factory called KED. (Author’s note: I run this club night with Ernesto Chahoud and Jackson Allers).

Ernesto Chahoud, a compiler and DJ who co-founded the BGC in 2009, says: “Many of Taroub’s records have catchy modern pop melodies and Middle Eastern hard-hitting percussive beats.

“That along with her beautiful voice makes it a perfect exotic blend for current underground international clubbing music.”

Many covers of Taroub’s songs have appeared over the last 10 years too, popular among contemporary Arab pop stars including Haifa Wehbe and Aline Khalaf. Though their updated versions of songs like ‘Aman Doktor’ have a decidedly more commercial sheen, they’re proof of how timeless her melodies are.

"It makes me happy to see my songs being played again, because they have a history,” says Taroub. “They were very well established and that’s why they’re coming back again.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.