Mostafa's story: How an Egyptian woman finally got her baby boy

“Mummy, tell me the story,” Mostafa asks Rasha Mekky, as she tucks him into bed.

And so Mekky begins to tell her five-year-old son, as she does every night, how she met him at an orphanage in Cairo’s Maadi district, when he was just four days old.

But their story begins well before Mostafa’s arrival in her life, before orphanages or IVF - before Mekky had even met her partner.

“I always dreamt that I would have ten kids,” Mekky says. “All my life I always loved babies and kids. My friends always thought I would be the first one to get married and have a tonne of kids. I was the oldest cousin in my family from both sides, my mum and my dad. And I always took care of anybody that was younger than me.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Mekky did end up being one of the first of her friends to marry, in 1993, when she was in her early 20s - but she was not the first to have children.

'All I was doing was just going through one in vitro after the other...I wanted a baby so badly'

- Rasha Mekky

She and her then-husband moved from Cairo to San Francisco, where Mekky decided to make a career change from tourism and hotel management to child development. Three years later she opened a daycare centre for toddlers and preschoolers.

It was around that time that Mekky, then 25, discovered that she suffered from endometriosis - a chronic condition where tissue similar to that which lines the uterus starts to grow elsewhere, such as the fallopian tubes or ovaries. Her doctors explained to her that her chances of conceiving a child were very slim.

And so they dived into the world of IVF. But the physical, financial and emotional costs were draining.

“All I was doing was just going through one in vitro after the other,” Mekky says. “Spending a tonne of money, borrowing money from my parents, applying for loans, whatever it takes. I wanted a baby so badly.”

After seven years and five rounds of fertility treatments, the results kept coming back the same. Following the breakdown of her marriage, Mekky moved back to Egypt, in 2004.

Alternative care

In the US, Mekky had been presented with a number of alternative options for having a child, such as sperm donation. But none that would have been acceptable in Islamic law.

“The term 'adoption' is never used in Arab Muslim countries as it is forbidden in Islam,” explains Nabila El Gabalawi, from the family programme of Face for Children in Need, a non-profit Belgian organisation that has been operating in Egypt since 2003.

Instead Egypt, like several other Arab countries, uses a system of alternative care for abandoned children, referred to in Arabic as "Kafala".

Kafala is similar to long-term foster care or guardianship, where abandoned children are not legally adopted but instead are raised as part of a family.

Unlike adoption, parents are expected to tell the child fostered through Kafala that they are not their biological children. The child is also expected to keep their birth surname, if known, in order to maintain clear bloodlines to ensure lines of patrimony and inheritance.

This applies in most countries whose judicial system is based fully or partly in Islamic law. There are some exceptions like Tunisia, where formal adoption is legally permitted.

“But the care for orphans is a duty that is emphasised in the Quran and Sunnah [religiously prescribed practice],” El Gabalawy says. “There are in fact several fatwas that encourage families to take on a child through the Kafala system.”

One such fatwa issued by the Egyptian religious institute Dar al-Ifta encourages unmarried women to sponsor a child through the alternative care, or Kafala, system.

In 2014, a committee was formed by the Ministry of Social Solidarity to help streamline the process and encourage awareness, including a video campaign. Egyptian regulations have been updated in recent years to widen the pool of possible candidates, now also including single and widowed women over the age of 30.

Finding Mostafa

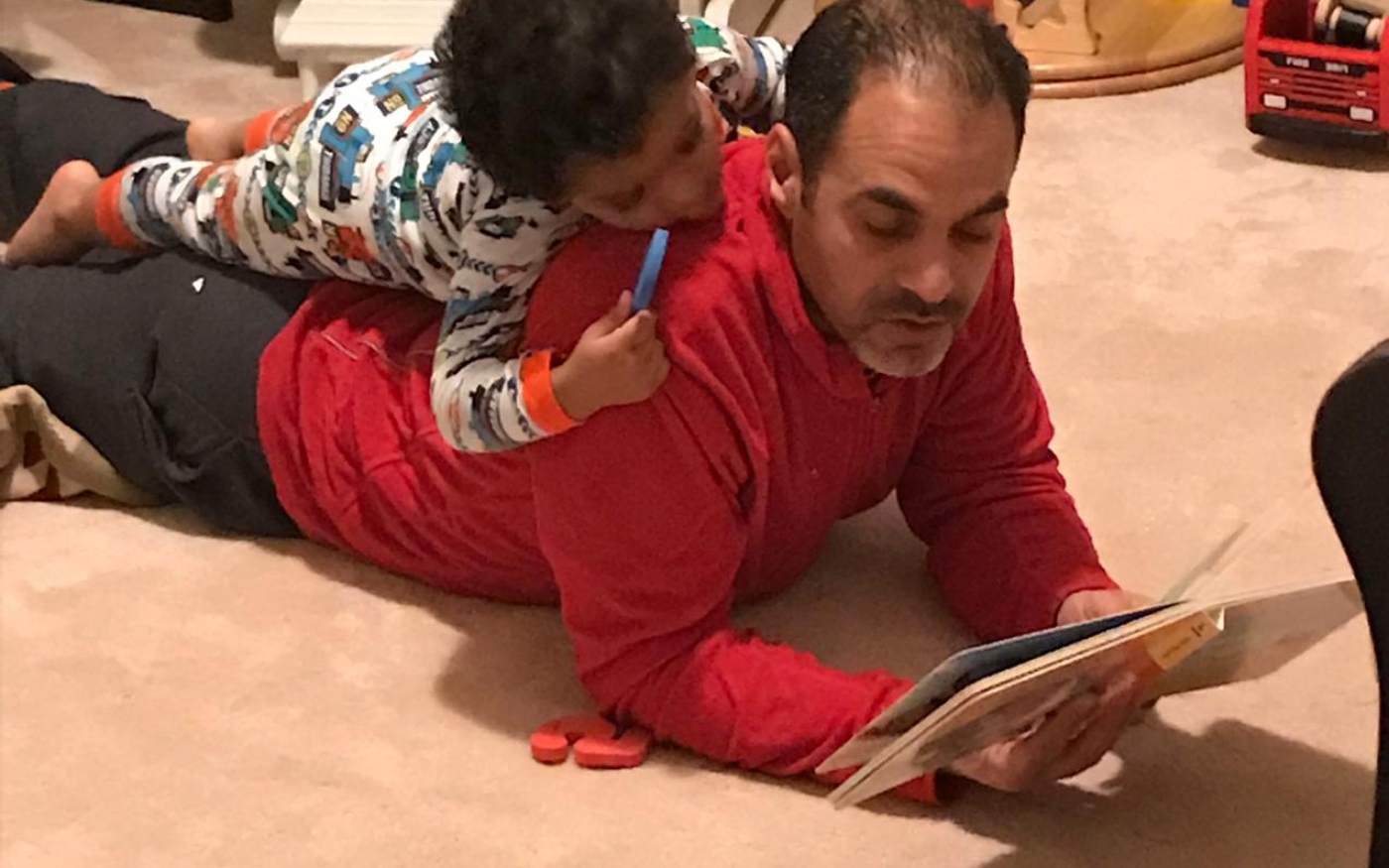

Mekky met her current husband Mohamad Eleraky in 2012. Eleraky had two daughters from a previous marriage, aged 7 and 11 at the time, and it was his support that would reinvigorate Mekky's quest for a child.

“He knew so badly how much I care for kids, that I love kids so much," Mekky says. "And right away he started asking [around] with me, we started digging [into] where and how can we adopt?"

But the process was not straightforward. It would take the couple a full year to gather all the necessary information and paperwork for their application before it was approved. And when they finally received the good news, they initially chose to keep it a secret.

She began to question herself: “Am I doing the right thing or not? Would I bring up a kid at this age? When do I have time to raise that child? Do I have the energy to play with that child?”

“I was 44 at that time, and it's so hard at that age, over 40. You already have your life set up,” Mekky says.

But armed with their approval, Mekky could now visit orphanages in search of a child.

Mekky had always dreamed of having a baby girl: during the decades she had collected suitcases full of baby clothes for girls, along with a now-defunct 15-year-old breast pump that she had bought during her fertility treatment days.

And when she made calls to orphanages across Cairo, she would always ask them the same question: did they have a baby girl? If they said no then she would hang up.

Mekky visited an orphanage near to her in the district of Maadi, but was not drawn to any of the babies she saw. “I thought in my mind, it's like a movie,” she says. “Once you see your kid you're going to click and that something was going to happen magically. But that didn't happen.

“I got a little bit depressed for a couple of weeks and then I decided, you know what? Okay, it's not a movie. I'm just gonna have to go pick a child.”

'I did not want a boy... But I looked at those eyes - he was an infant, four days old, looking at me'

- Rasha Mekky

Mekky was on the lookout for a baby girl with tanned skin, or at least dark hair, so she would look similar to her future parents.

Then, on one of her visits to the orphanage, she overheard the staff talking about two children who had just been abandoned and due to arrive at the orphanage the next day following a checkup at the hospital - a boy and a girl.

Hopeful, Mekky rushed to see the girl first thing the next morning: “And guess what?” Mekky says. “Blondie. Blonde, blonde, like white hair. Very, very fair and blue eyes."

But Mekky was destined to have her movie moment after all - and a baby.

“So I look at the next crib and… Mr Mostafa was there. I did not want a boy... But I looked at those eyes - he was an infant, four days old, looking at me. I held him from the crib, could not let go for five straight hours.”

During those five hours, Mekky didn’t leave Mostafa’s side. She fed him, changed his nappies and held him tightly, afraid that another family would come and choose him before she had a chance to put in her application.

As soon as that application was processed, Mekky visited a gynaecologist to begin the medication which would trigger her milk flow, since she wanted to be able to breastfeed him. Six weeks later, in January 2015, Mekky and Eleraky stood in a room with three other couples whose applications were also completed, waiting to be handed their new child.

"It felt absolutely normal," Eleraky says. "This was my son."

Bringing home baby

Back home, things didn’t go as smoothly as Mekky had expected.

“When you are pregnant for nine months, your body is preparing you and your mind is preparing you that there's a baby coming,” she says.

“But we went and picked him up and came home with an infant, that wakes up every three hours, wants to feed every three hours, every time he cries, bottles everywhere, clothes and baby clothes, everywhere.”

The sudden change severely affected Mekky’s mood and led to a bout of insomnia. But after she was diagnosed with post-natal depression and prescribed the medication that would ease the symptoms, she was ready to celebrate his arrival.

This time, she broadcast the news, inviting all her friends and family to a large, traditional aqiqah gathering, usually arranged to mark the birth of a new baby.

In April 2015, Mekky and her husband decided to move to San Francisco for work, taking Mostafa along on a tourist visa initially until they could apply for his permanent US residency.

Mekky found herself buried in paperwork once again as she discovered she would have to "readopt" Mostafa in compliance with California state laws, before applying for his immigration status: “I started off trying to apply and they said you have to have a lawyer and you have to do a home study. And you have to do the whole thing from scratch again."

The process was longwinded. By January 2019, Mostafa’s completed immigration application was finally filed by her lawyers in the US.

But the family was due another shock: Mekky was informed that she and Mostafa, now four years old and settled into life and school in California, had 90 days to leave the country, while their case was being reviewed.

They left for Egypt, not knowing if and when they would be back.

Growing an online presence

Having stayed behind in California, Eleraky was left to wait while his wife and son were away indefinitely.

"I would sleep for two hours and just keep answering more questions and talking to people.”

- Rasha Mekky

In the meantime in Cairo, Mekky had already begun to urge other Egyptian women struggling with IVF to consider Kafala instead.

Mekky eventually started a Facebook page where people could contact her directly and where she could post news about her story and others like hers, and to help break down a process that can feel overwhelming.

One day, she woke up to find that one of her posts had been shared 2,500 times and that her phone was “on fire". Within a week the post had been shared 4,500 times.

"I kept answering women and families until 2 and 3am," she says. "I would sleep for two hours and just keep answering more questions and talking to people.”

She was inundated with Egyptian women asking her questions and sending her virtual prayers: “My inbox filled up… It was just non-stop."

Within just two weeks, the wait was over: Mostafa received his immigration clearance and they were able to return to the US.

Today, Mekky is more motivated than ever to share her story with the world, sharing a guide in English on the criteria required on the Kafala process.

Her posts are often in English and Arabic, to encourage Egyptians living abroad to foster an Egyptian child and help "empty all the orphanages [in Egypt]," which, Mekky says, is her biggest aim.

Along with a growing number of volunteers, she set up a website and social media accounts, aiming to help other Egyptians considering alternative care options, and to champion other success stories.

Through meeting others in Egypt and the US with similar struggles and charitable organisations like Belgium's Face for Children in Need and Wedad Charity Foundation, Mekky has started to create a support group for Kafala families to share their own experiences and to address some of the stigma they might face.

One of the group’s projects is to translate English picture books that teach children about adoption into the Egyptian dialect. They publish these as videos dubbed with audio translations.

Their first video is a translation of A Mother For Choco, by Keiko Kasza. In the story, Choco, a lonely blue-beaked yellow bird, wanders round in search of a mother, but cannot find any other creature that looks like him.

Eventually, he happens upon Mrs Bear, who welcomes him into her home as her son. When Choco meets her other children - a hippo, an alligator and a pig - he finds what he’s been missing. The children all snuggle up on their mother’s lap, their faces beaming. Choco is happy that “his new mommy looked just the way she did”.

Mostafa’s story

Now five-years-old, Mostafa has started asking his mother if they can “go and get a baby from the place that you said has babies that don’t have mummies and daddies”.

“This is what you want,” Mekky says. “And he’s not sad. He looks at it as a happy thing.”

And from the beginning of their journey, Mekky has insisted on Mostafa’s right to know his background, from the very first time he asked.

When one day, Mostafa, aged about three, came home from school and said, “I know the babies come from your tummy,” Mekky knew that he was ready to learn the truth. “So I told him,” she says. “That he comes from my heart.”

And that’s when “Mostafa’s story” was born, and added to his bedtime routine. As Mostafa grows, so do the layers of the story: “Now it's involving more characters that he knows, like my friends,” Mekky says. “And he can tell you the whole entire story.”

It is clear, as she acts it out, that Mekky gets as much joy from this story as Mostafa. She tells him how much she had wanted a baby, even when her doctor told her she couldn't get pregnant. “Mummy went and looked in that place that one of her friends told her has a lot of babies that don't have a mummy or a daddy.

"So I went, and looked around, and looked around, and looked around and - oh! I found,” - she pauses for effect, before launching into her son’s delighted response - “‘Mostafa!’”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.