Unrequited love: The epic romances of the Arab world

The themes that enraptured the Arab poets of the past will be familiar to anyone who has felt the pangs of love in any of its different guises: the passionate, the eternal, the unrequited, and the ill-fated.

In Arabian tribal societies, love, honour, and war were inseparable and the canon of Arabic poetry is full of tales of deception, gallantry, and heartache all in the pursuit of a beloved.

In traditional Bedouin societies, the idealised concept of love was intense, precious and something to be fought over. Poets sought to reflect this and embody these values in the oral form.

The figures that appear in the stories below were largely fictional but often based on real-life characters, with legend replacing fact over the repeated telling and poetic embellishments:

Layla and Majnun

Based on the purported real tale of Qays ibn al-Mulawah and Layla Al-Amiriya, of the Bani Amer tribe from Najd in pre-Islamic Arabia, this tale is the classic story of two lovers kept apart by circumstance.

Although the pair grew up playing together, when they reached adolescence they were kept apart due to the Bedouin tradition of segregating the genders.

Unfortunately for Qays, he had already become besotted by Layla, and being deprived of his beloved sent him into a mental decline that led to him earning the sobriquet "Majnun", meaning crazy.

Layla had also fallen in love with Qays. But while she was circumspect in the way she expressed her feelings for him, Qays wanted the world to know, and recited odes to Layla through the streets where they lived.

Even after his marriage proposal was rejected by Layla’s father, Qays refused to relinquish his love and he started to write of his tragic devotion on the walls of buildings.

I pass by these walls, the walls of Layla

And I kiss this wall and that wall

It’s not Love of the walls that has enraptured my heart

But of the one who dwells within them

Public displays of love in this manner were seen as dishonourable in traditional society and could affect a woman's reputation.

Layla’s family married her to Ward Althaqafi, a wealthy merchant from the Thaqif tribe in Taif.

News of the union only intensified Qays’ burning heartbreak and threw him deeper into insanity, leaving him wandering the desert in perpetual grief.

In one later version, his father finds him and convinces him to make the pilgrimage to the Kaaba, to overcome his heartache, but once there Majnun prays to fall even deeper in love with Layla.

They tell me: “Crush the desire for Layla in your heart!”

But I implore thee, oh my God, let it grow even stronger

After the death of her husband, Layla sets out to find Qays. But culture and tradition will not allow this, leaving a longing Layla to die anguished and alone. Qays then finds her grave and dies beside it, and they are finally united in death.

Sufi poets consider Majnun’s all-encompassing love for Layla as symbolic of humanity’s quest to reach God.

The enduring tale has been reinterpreted and shared frequently since its first recorded iteration in the fifth century CE. The first written version of this eternal tale of longing is credited to Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, an Arab poet who wrote Kitab al-Aghani or the Book of Songs in the ninth century.

A few centuries later, the Persian poet Nizami Ganjawi penned his own version in verse.

(All illustrations by Mohamad Elasaar)

Jamil and Bouthaina

Another tale from Bedouin Arabia centres around Jamil ibn Abdullah ibn Mamar, a camel-herder who lived in the sixth century CE and belonged to the Banu Udhra tribe. Like Qays, his lost beloved inspired a subgenre of Bedouin love poems, in which love is yearned for but never consummated.

Jamil falls in love with Bouthaina bint Hayyan after becoming fascinated by her feisty character. According to the story, he was tending to his herd of camels at a well in the desert when the arrival of a different flock scared his animals away.

The new arrivals belonged to Bouthaina, and out of anger, Jamil insulted both her and her camels. But instead of cowering in response to his anger, Bouthaina is said to have retorted with an insult of her own.

He was impressed, her spirited response was enough to captivate Jamil’s heart, and he thought he had met his match.

To express his love, he composed poetry. But his words of admiration were misunderstood by the community who assumed the two had conducted an illicit affair. When Jamil went to propose marriage, Bouthaina’s father refused and instead married her to another suitor.

Oh, that youth's flower anew might lift its head

And return to us, Bouthaina, the time that fled!

And oh, might we bide again as we used to be

When thy folk dwelt nigh and grudged what thou gavest me!

Her family also vowed to kill Jamil for trying to dishonour their daughter and issued a death warrant.

Jamil, now broken-hearted and fleeing for his life, escaped to Yemen where he committed himself to compose poetry in Bouthaina's memory.

One version of the tale says the two never saw each other again.

On his return to his tribe, Jamil discovered Bouthaina had moved to the Levant. Another version suggests he returned and the two met in secret. Though Bouthaina had married, Jamil stayed celibate as an expression of his devotion to her.

Antarah Ibn Shaddad and Ablah bint Malik

Another ancient Arabian love story - and perhaps one of the first to deal with the issue of race - is that of Antarah Ibn Shaddad, the son of King Shaddad Al-Abs of the Banu Abs tribe in Najd and an unnamed woman who was said to be an Ethiopian slave.

Antarah was born in 525 CE, only to be abandoned by his father at birth, due to his maternal lineage and darker skin colour.

He was subsequently treated like a slave instead of the son of a king, but the valiant Antarah never stopped seeking the validation from his father. He fought bravely in tribal battles, proving his strength and swordsmanship, and helped stave off threats from rival tribes.

But while his heroics earned him the respect of his fellow tribesmen, this was not enough to allow him to marry the woman of his choosing.

He hoped to wed his cousin Ablah bint Malik, but her mother tried to entice Antarah with other prospective brides, all of whom he refused.

Her father then demanded a dowry of 1,000 expensive and rare camels bred only by King Al-Nuaaman Ibn Al-Mondir from Al-Hira in Mesopotamia.

But Antarah took on the challenge and made his way to Al-Hira returning with the camels as a gift for his beloved’s family. But instead of finding his love, his scheming uncle had already betrothed his daughter Ablah to another man in exchange for murdering Antarah.

Antarah's fate varies but most versions of this tale suggest the two would-be lovers were never united, with Antarah spending his remaining years longing for her and reciting poetry in her memory:

My sin against Ablah is beyond remission;

Became obvious when the morning of life

Lent streaks of its white shafts

To my hair, turning it gray.

My own Ablah pierced my heart with arrows,

Shot from her white-corona, black-iris eyes;

Accurately hitting the mark!

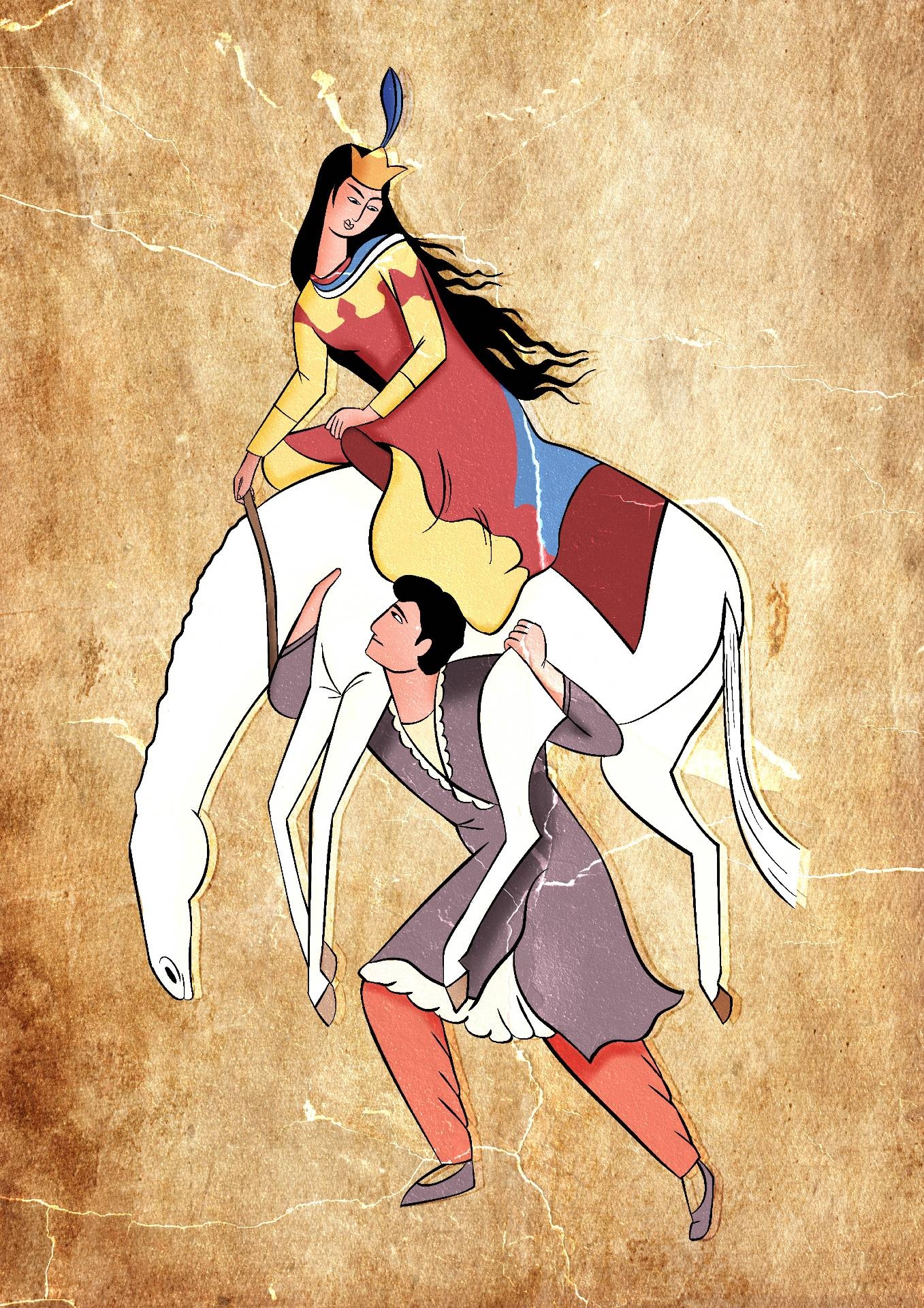

Saif-ul-Mulook and Badi-ul-Jamal

Although this tale is set in Egypt, it is now more popular in Pakistan thanks to a translation by Mian Muhammad Baksh, a 19th century Sufi writer, and the contemporary Pashtun poet Ahmad Hussain Mujahid, who produced his own version of the story.

The story can also be found in One Thousand and One Nights, where Saif-ul-Mulook (meaning Sword of the Kings) is a wealthy Egyptian prince and the only child of a fictitious Egyptian king named Asim bin Safwan.

The king bequeaths two sovereign stamps to Saif, one with the prince’s face on it and the other with the face of a mysterious beauty named Badi-ul-Jamal.

At night the young prince has a dream of an enchanting lake where he encounters Badi-ul-Jamal, the woman from the picture. She introduces herself as the Queen of the Fairies and invites him into her fairyland - but warns there will be tribulations along the way.

Some versions of the tale say it was after this dream he went on his quest to find her; others don’t mention the dream and suggest instead that he fell in love as soon as he saw her image.

But either way, he begins a six-year journey in search of his beloved that ultimately leads him to an emerald green lake where, on the advice of a saint that he met earlier in Egypt, he must offer 40 consecutive days of prayers in order to be united with Badi.

On the 14th night of his prayers he finally sees seven heavenly fairies - and there among them is the majestic Badu-ul-Jamal, bathing in the lake.

After discovering Badi has been trapped by the white giant Safaid Deyo he frees his love and they escape to a nearby cave.

The giant sheds tears when he discovers Badi has been released and these come to form the Ansoo Lake (Tear lake) in Pakistan’s Kaghan valley, which sits beside Saif-ul-Mulook lake.

Some say the Egyptian prince and his fairy queen still live in the valley and dance above the lake on the 14th night of the lunar month - and many locals still like to believe the area is filled with fairies and demons.

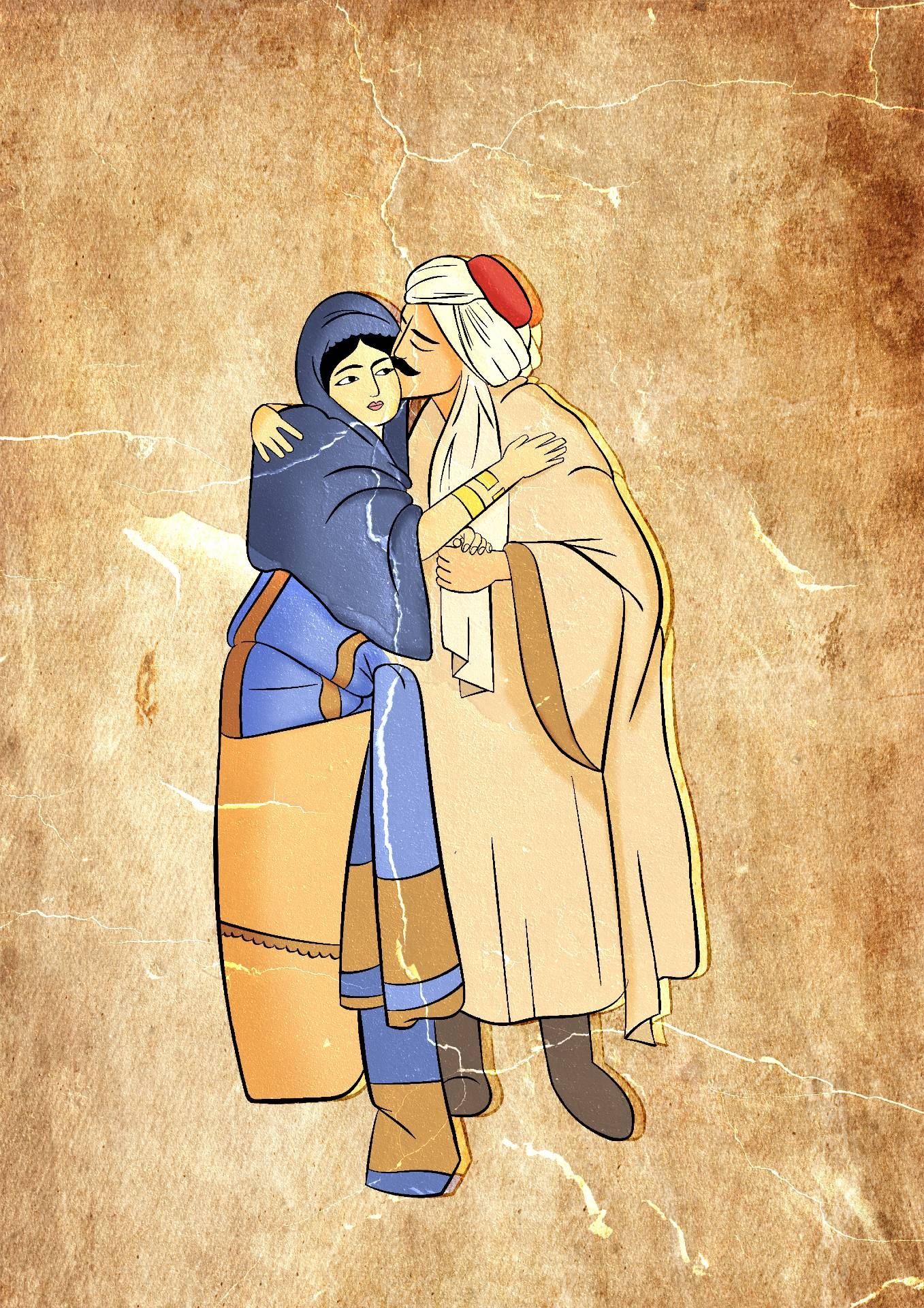

Qutuz and Gulnar

Saif ud-Din Qutuz and his love Gulnar (or Jelnar) were said to be nobles from the Khawarizmian Empire in Persia who were both captured by Mongol invaders and sold into slavery.

Interestingly, unlike the other stories featured here, theirs is a tale rooted more in contemporary Arab culture than in the ancient world with 20th century Egyptian writer and poet Ali Ahmed Bakthir producing the most definitive version.

Gulnar’s character was first introduced to modern readers by Bakthir in his novel Wa Islamah (Oh Islam!). But Qutuz is based on the Mamluk sultan of Egypt, who was taken to Damascus by the Mongols where he was bought by an Egyptian slave merchant who sold him on to the Mamluk Sultan Aybak.

Qutuz proved himself to be a strong soldier and honest advisor, rapidly climbing the Mamluk ranks and becoming a deputy to Aybak. Around this time, he was reunited with Gulnar, who had been sold by the Mongols to a wealthy Egyptian family, where she had been working as a servant.

Gulnar becomes a confidante and lover to Qutuz as he goes on to become sultan of the Mamluks and leads their armies to victory against the Mongols at the Battle of Ayn Jalut (1260 CE) with his beloved at his side.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.