Love, poetry and pan-Arabism: The broken dream of Balqis and Nizar

“Scattered” is invariably the adjective that comes up when my family talks about Iraq, as it describes the primary consequence, for us, of the US invasion and the fall of Baghdad in 2003. We packed up and left our homeland. We scattered, taking with us our memories, good and bad.

All those who have returned to Baghdad have shared the same impression: a city without its souls no longer has the same feeling.

Like so many Iraqi families, mine was forced to sell the house we had lived in for three generations. The situation in the country is such that many families from Iraq’s middle class have sold their property to move abroad. For most, the hoped-for return to their homeland has been postponed, if not forgotten entirely.

Treasured memories

Baghdad has undergone substantial demographic change, and the families that gave the city its greatness left behind them many memories of pleasant neighbourhoods, love stories, friendships, and folklore orphaned from the people who carried them.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

We brought with us family memories, which our parents have tried to pass on to us so that we don’t forget our history. It’s the only treasure one can offer to new generations when everything has been lost, or nearly so.

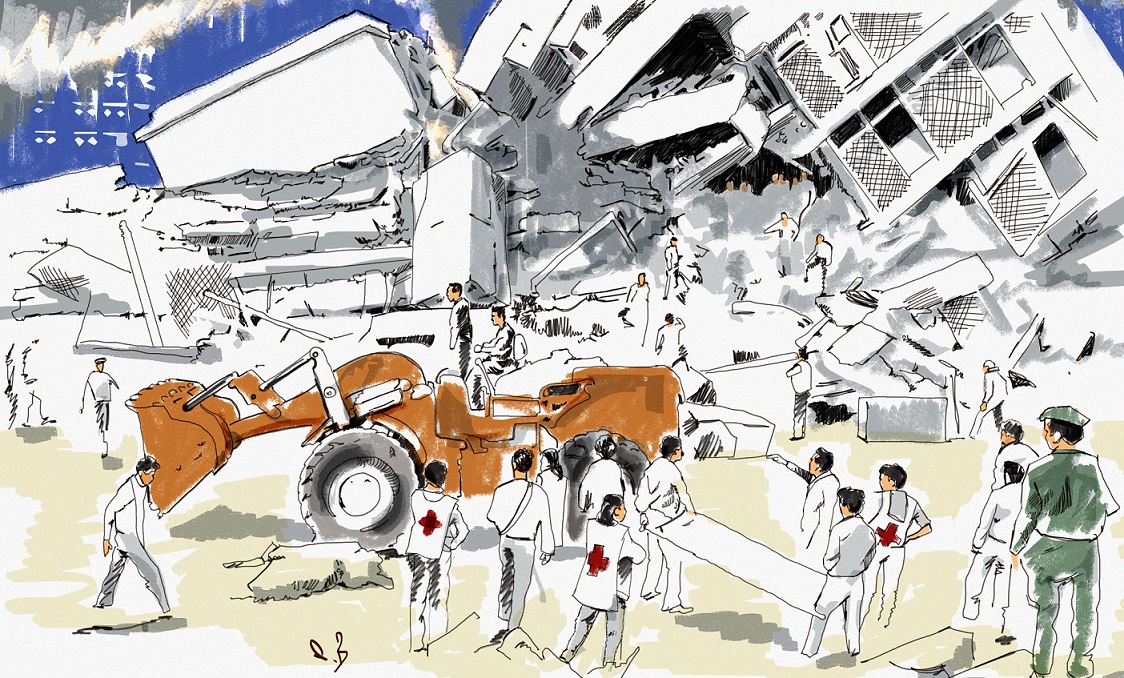

The car was filled with explosives. It passed through the embassy gate and parked in the basement, and moments later, the entire three-storey building collapsed

Among these memories, there is one that has marked me more than the others. I didn’t live through it personally, because I wasn’t born at the time, but it’s an event that we commemorate each year. Every 15 December, we write articles on the subject or publish - as one does in this digital era - messages on social media.

The event unfolded in the dead of winter in Beirut, then in the grip of civil war. On 15 December 1981, at noon, a car stopped in front of the Iraqi embassy in the Lebanese capital. By that point, Iraq had been at war with Iran for months. Balqis al-Rawi, wife of the great Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani, had been working in the Iraqi embassy’s press service, which had been led for a year by my grandfather’s brother, Harith Taqa.

Balqis and Harith had adjacent offices. The friendship between their respective families dated back some 10 years, when Nizar came to Baghdad for the poetry festivals in which my grandfather, Shathel Taqa, also participated.

‘In her eyes was violet’

The car was filled with explosives. It passed through the embassy gate and parked in the basement, and moments later, the entire three-storey building collapsed. The Iraqi state had just been struck, right there in the heart of Beirut. Among the dead were Harith and Balqis, Nizar’s beloved, the one to whom he would dedicate one of the most painful pieces of modern Arabic poetry:

Do you know my darling Balqis?

She is the most important text of the works of love,

She was a sweet mix

Of velvet and marble.

In her eyes was violet

Sleeping without sleeping.

Balqis,

Perfume in my memory!

O tomb, travelling in the clouds!

They killed you in Beirut, like just any gazelle,

After killing speech itself.

Balqis,

This is not an elegy,

But to the Arabs, a farewell,

Balqis,

We miss you... we miss you... we miss you...

“A Poem for Balqis” (1982)

According to her sister, Nibal, Balqis was supposed to have left the embassy earlier that morning to buy some videotapes for her two children, but she hadn’t managed to, thanks to the mound of work she had to finish.

Had Harith guessed that something was afoot? His friends say that before he left for Beirut, just after finishing his mission in Rome, he had uttered a phrase that had taken them by surprise. After inviting them to gather around him, he had told them: “Come and take your last picture with me.”

Even today, we recall this ominous statement with a shiver. All is written, and Harith had felt it.

Baghdad, lovers’ nest

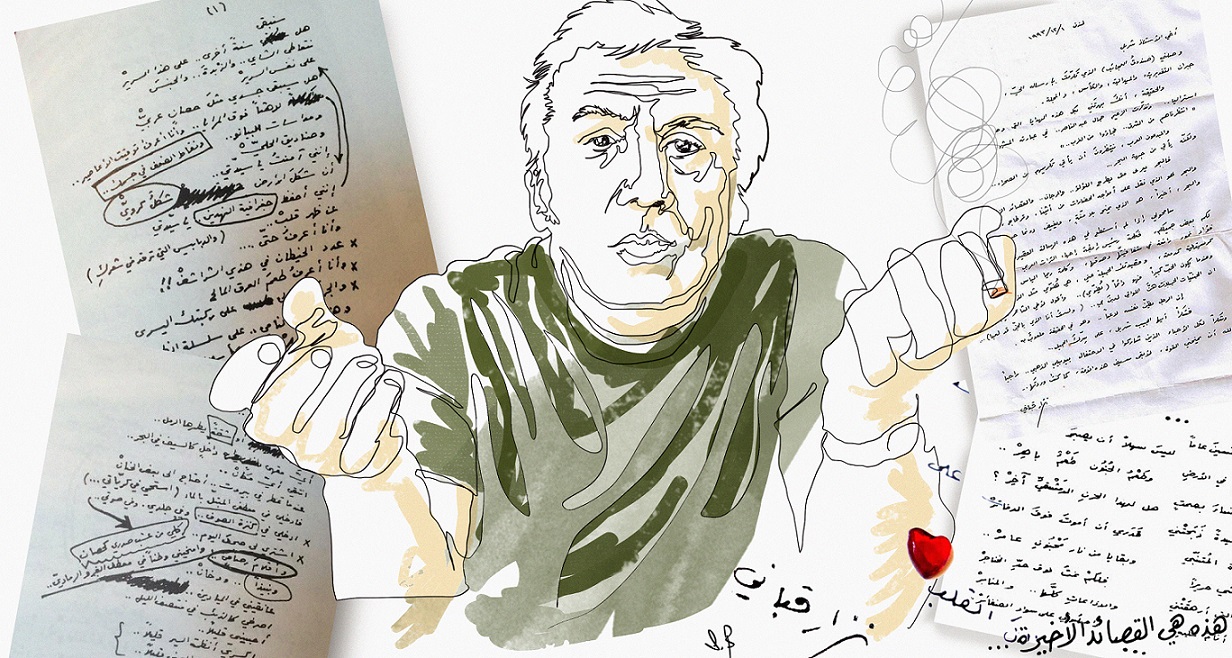

Following Balqis’s death, Nizar was inconsolable. He would never again write of love, and all his talent would from then on be invested in unmasking the cowardice of Arab leaders. And yet, Balqis and Nizar’s story had started so well, more than 10 years earlier in Baghdad.

It was 1969, and the ninth Arab Poetry Festival was being held in Iraq's capital. These festivals, which took place each year in a different Arab city, were not only literary in their focus; they were also an opportunity for Arab poets to proclaim their support for pan-Arab causes.

Two years earlier, the Arab world had awoken in a state of shock after the 1967 Israel debacle. The morale of the Arab street was at its lowest point, and it was therefore urgent for Arab intellectuals and poets to re-mobilise the peoples of the Arab world to face the challenges ahead.

Nizar was at that time one of the great names of the Arab literary scene. He was distinguished by a peculiar feature: He addressed Arab women directly, singing their praises, wooing them, and addressing to them his most beautiful verses. In short, he put Arab women on a pedestal.

Dedicated verses

His poems were picked up by great singers on the Arab scene, from Umm Kulthum, to Mohammed Abdel Wahab, to Abdel Halim Hafez. This Damascus native didn’t hesitate to write about all the important themes of the time, exercising a certain freedom and even irritating some.

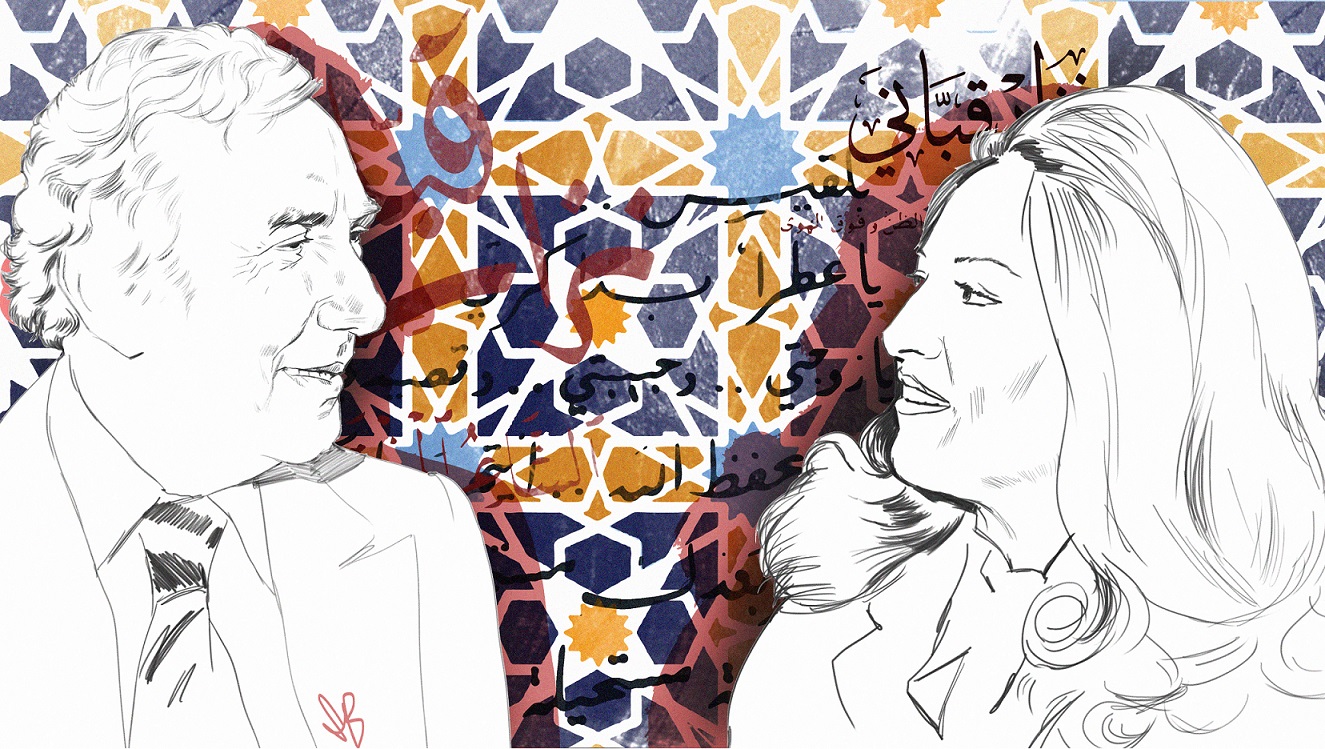

In 1969, Nizar was in Baghdad for the poetry festival, but not only for that reason. He was in love again, and this time his heart beat for a young Iraqi woman: the daughter of an Iraqi officer, Balqis al-Rawi was a teacher in Baghdad.

It was during a poetry recital that Nizar met Balqis. After that meeting, he couldn’t get over her

Like many Iraqi women of her day, she enjoyed a social environment that encouraged women’s freedom and education. As was also common for Arab women at the time, Balqis was a committed activist. She was swept up by the prevailing pan-Arabism and took part in an Iraqi women’s committee in support of the Palestinian cause.

It was during a poetry recital that Nizar met Balqis. After that meeting, he couldn’t get over her. At the end of the festival, Nizar dedicated one of his verses to his sweetheart: “What is this beautiful face that I see in Adamiya", he wrote, referring to a neighbourhood of Baghdad, "if Heaven saw it, it would be jealous".

The Syrian poet decided to go for it, and presented himself to Balqis’s father to ask for her hand. Her father did not believe his request was serious, and refused Nizar several times.

Romantic woes

Nizar’s romantic woes reached the ear of the Iraqi president at the time, Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr, who was upset by the news and did not hesitate to call Balqis’s father personally. The socialist president didn’t stop there, either. He sent two of his colleagues, also poets and friends of Nizar, to visit the father. Shathel Taqa, my grandfather, who served in the ministry of information and later foreign affairs, was joined by Shafiq al-Kamali, who became youth minister in 1970. Balqis’s father was obliged to yield.

Too young at the time, at age 11, to remember the exact details of the event, my father does clearly recall Nizar and Balqis’s visit to our family home. He had hoped to be among those invited into the guest room, but it was a lost cause; he was only given the right to enter and greet the guests alongside his sisters.

My father later learned it was in that meeting that the couple took the opportunity to announce their union. Several of Nizar’s friends were present, including Palestinian writer and psychiatrist Ali Kamel, the famous Iraqi physicians Ghazi Jamil and Saniha Amin Zaki, and others whose names my father cannot recall.

At the time, the days of the modern poetry festival seemed endless, and my grandmother complained that she no longer saw her husband. Nizar, Shathel and the other poets held informal poetry salons, even after the end of the festival sessions.

End of an era

Nizar and Balqis moved to Beirut, where many intellectuals and leading men and women of letters from across the Arab world lived at the time. As one well-known adage in the region put it: “Egypt writes, Lebanon prints, Iraq reads.”

In a letter that Nizar sent to my grandfather in 1974, congratulating him on his appointment as foreign minister, the poet of Damascus encouraged him not to be drawn in by politics at the expense of poetry.

It was an era for patriotic commitments, and this allowed her to serve her country in the name of the pan-Arab values she cherished

Nizar also described in this letter how Iraqi culture had pervaded the atmosphere in his house ever since his marriage to Balqis. The poet cited the smell of the famous bamya (okra sauce with meat) that Iraqis eat with rice, along with other Iraqi specialities.

My grandmother can recount a visit she made to the couple the same year. Balqis picked her up at the Beirut airport, accompanied by Iraqi writer Daisy al-Amir. She stayed a few days with her friends before returning to Baghdad. When my grandfather died a few months later while attending a ministerial summit in Rabat as foreign minister, Nizar sent a cable to my grandmother, saying: “He was your beloved, our beloved, he was the best of men.”

In the late 1970s, life was complicated for Nizar and Balqis. The state of insecurity made moving about in Beirut difficult. Social life consisted of a few meetings with a handful of friends near their home.

Despite the risks, however, Balqis didn’t hesitate to join the staff of the Iraqi embassy in Beirut. It was an era for patriotic commitments, and this allowed her to serve her country in the name of the pan-Arab values she cherished.

Shock and devastation

It took several days for the civil protection forces to find the bodies of Balqis, Harith and their colleagues. The entire Arab press repeatedly denounced this hateful crime. These were innocent people still in the prime of their lives.

My father recounts a scene when poet Hashim al-Taan came to our family home, distraught, to inquire about his friends. When my grandmother informed him that Harith was still under the wreckage and that she still had no news of him, he placed his hand over his heart in a sign of his devastation and stumbled back outside. Passersby found him collapsed on the ground, unconscious, a few steps from our home. He died a few minutes later.

The death of Balqis held something symbolic, seeming to take the Arab world from an era of hope, conviviality and love and into another cycle of war, extremism and hatred

Nizar Qabbani was never the same after this event. He left Beirut and took refuge in London. Love had departed the Syrian poet for good. From then on, he wrote only caustic poems aimed at the political authorities of the Arab world.

The death of Balqis held something symbolic, seeming to take the Arab world from an era of hope, conviviality and love and into another cycle of war, extremism and hatred.

For contemporary generations - who have only photographs as evidence of an era when the Arab world could conceive of what happiness meant - that period seems almost inconceivable today. The tragic end of the couple, Balqis and Nizar, marked the end of a beautiful era.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This piece originally appeared in the MEE French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.