A century of revolutionary Arab art

The Barjeel Art Foundation has brought a selection of its art collection from Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates to east London’s Whitechapel Gallery.

While the exhibition is deceptively modest, taking up only one room in the gallery, there are remarkable treasures here by some of the last century’s most influential Arab artists.

Barjeel founder Sultan Saood al-Qassemi has described the exhibition, Imperfect Chronology, as “the most expansive and inclusive display of modern and contemporary Arab art anywhere in the world,” and with some justification.

From rarely seen sketches by Lebanon’s Khalil Gibran, author of The Prophet, to major works of modern art from Algeria to Syria, it offers a sweep of the region’s art movements from the turn of the 20th century to the height of the Arab Cultural Renaissance in the 1960s.

For those, like this writer, who are not familiar with the Arab artists on display, it is no less than a window onto the emergence of modern art in the region, starting with figurative, almost Orientalist landscapes from the 1900s by Youssef Kamel and Mahmoud Said, through surreal and abstract works, Effat Nagi’s constructivist paintings celebrating the building of the Aswan Dam in Egypt, overtly political works that speak to the region's emergence from colonial rule, religious pieces and other more personal and sensual examples of portraiture.

The variety of styles on display is striking, and the parallels with western art of the time are clear. Many of the artists on display had trained in the West, while also being founders of revolutionary art movements in their own countries.

Iraqi artists feature prominently. Works by Dia Azzawi, probably Iraq’s most influential living artist, sit alongside poet and artist Kadhim Haidar, whose white horses depicting the martyrdom and mourning over Hussain Ibn Ali at the battle of Karbala was based on his own poem. After studying in London, he was a founding member of the Institute of Arts in 1960s Baghdad.

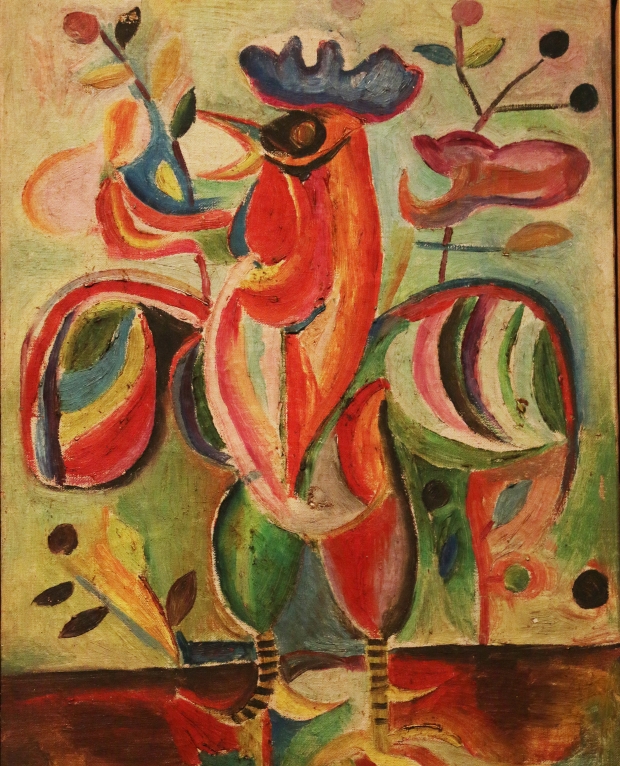

Shakir Hassan Al Said’s Articulated Cockrel is a masterpiece of joyous colour, and hints at his mix of influences from Sufism to Western artistic movements from existentialism to constructivism that he encountered while studying in Paris’s leading art schools.

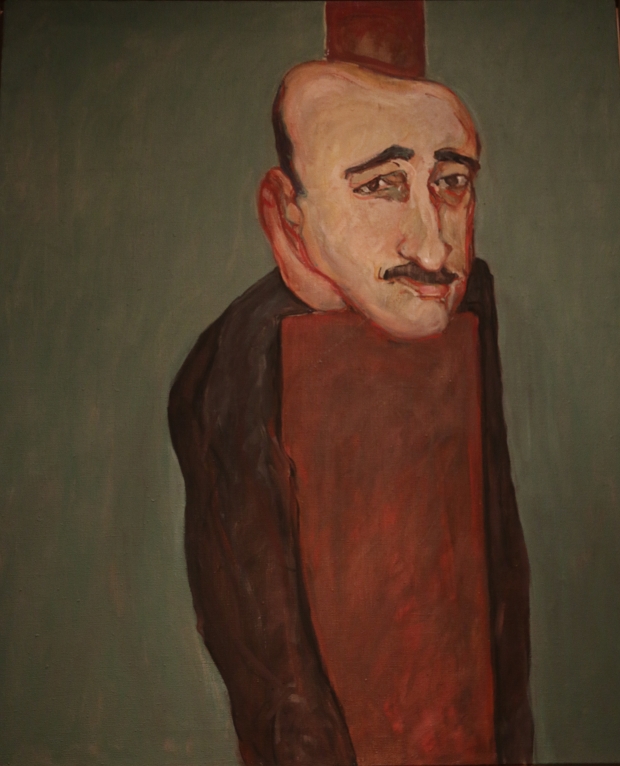

Renowned Syrian artist Marwan’s 1965 portraits of Munif al-Razzaz, former secretary-general of the Syrian Baath Party, ooze unease and melancholy, the gaze unsettling. Marwan moved to Germany in the late 1950s, painted at night and stayed there, becoming a member of its prestigious Akademie der Kunste and a major influence on a number of German artists. Some 200 of his works are displayed in the Berlinische Gallerie, as well as in Amman and Damascus.

Egyptian artist Inji Efflatoun’s series of black and white surrealist works are almost magically powerful in their evocation of injustice and sorrow. Efflatoun, who died in 1989, was a women’s rights activist and founder of the revolutionary Art and Freedom Group. The centrepiece in the seven paintings by her at the Whitechapel is The Dinshaway Massacre, depicting a man hanging from a door frame, while family members throw themselves to the earth in grief in the distance. It’s a portrayal of an infamous episode of British colonial cruelty from 1906 sparked when British officers hunted the pigeons of local Egyptians, before clashes and the hangings of several Egyptians as a warning from the colonialists.

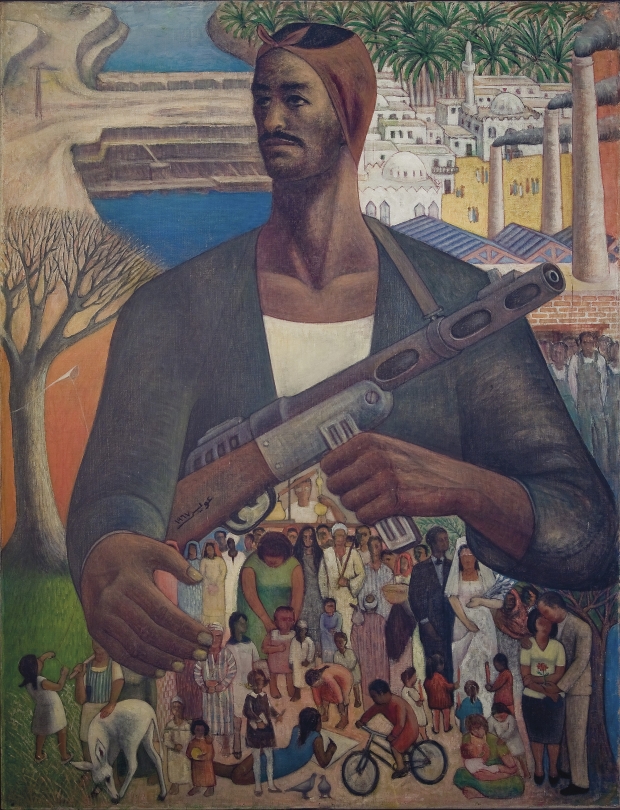

The anti-colonial politics of the era are to the fore – with two works, one from Algeria, the other Egyptian, in profoundly different styles. Hamed Ewais’s Le Guardien de la vie (1967-8) is a mural-style oil painting in the spirit of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, depicting a fighter, rifle in hand, who towers over a large group of ordinary people including newlyweds and a child riding a bike, suggesting that he is the last line of defence for Egypt and its people in the aftermath of the disastrous Six Day War.

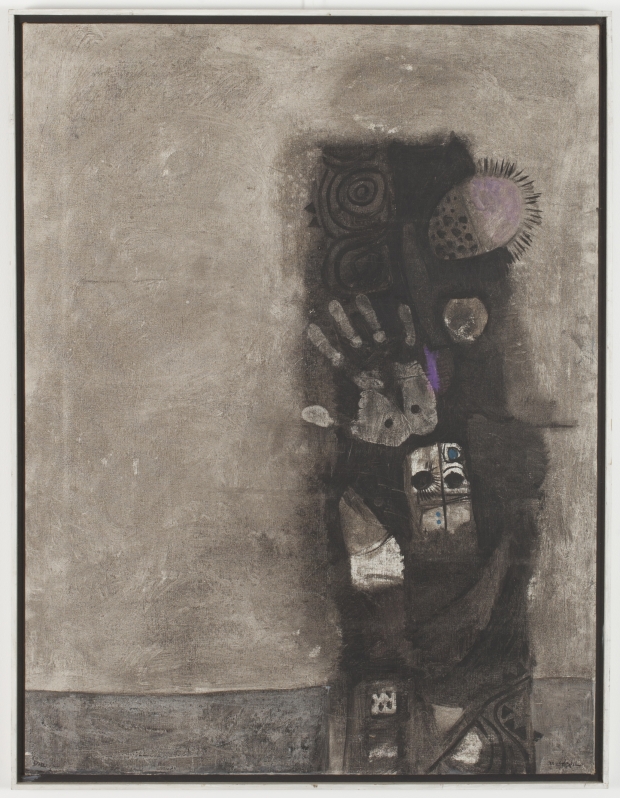

By contrast, the ghost-like image of a woman by Algerian artist Mohammed Issiakhem, is more personal. Femme at Mur is said to be a portrait of his sister, who was killed tragically along with another sister and his nephew when Issiakhem was playing with a grenade stolen from a military camp, which went off. In the painting, behind the figure of the woman, graffiti on the wall (“OAS” and “FLN”) suggests that the war of independence is not long over. Issiakhem recovered from this terrible incident to become a leading figure at the School of Fine Arts in Algiers and later director of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts of Oran, even designing the newly independent country’s banknotes.

It seems that behind every painting on display in the Whitechapel is the history of a nation being born.

Imperfect Chronology is divided into four successive exhibitions and continues over the next 15 months at the Whitechapel Gallery. Entry is free.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.