Fugitive traces: Nomadic artist inspired by Berber culture

We are sat in @Space50, a cavernous Victorian house turned studio in Mayfair where Iranian diaspora artist Firouz Farman Farmaian’s exhibition "Permanence of Trace" is on display. Bold, geometric patterns and Berber iconography dominate his art panels lining the walls.

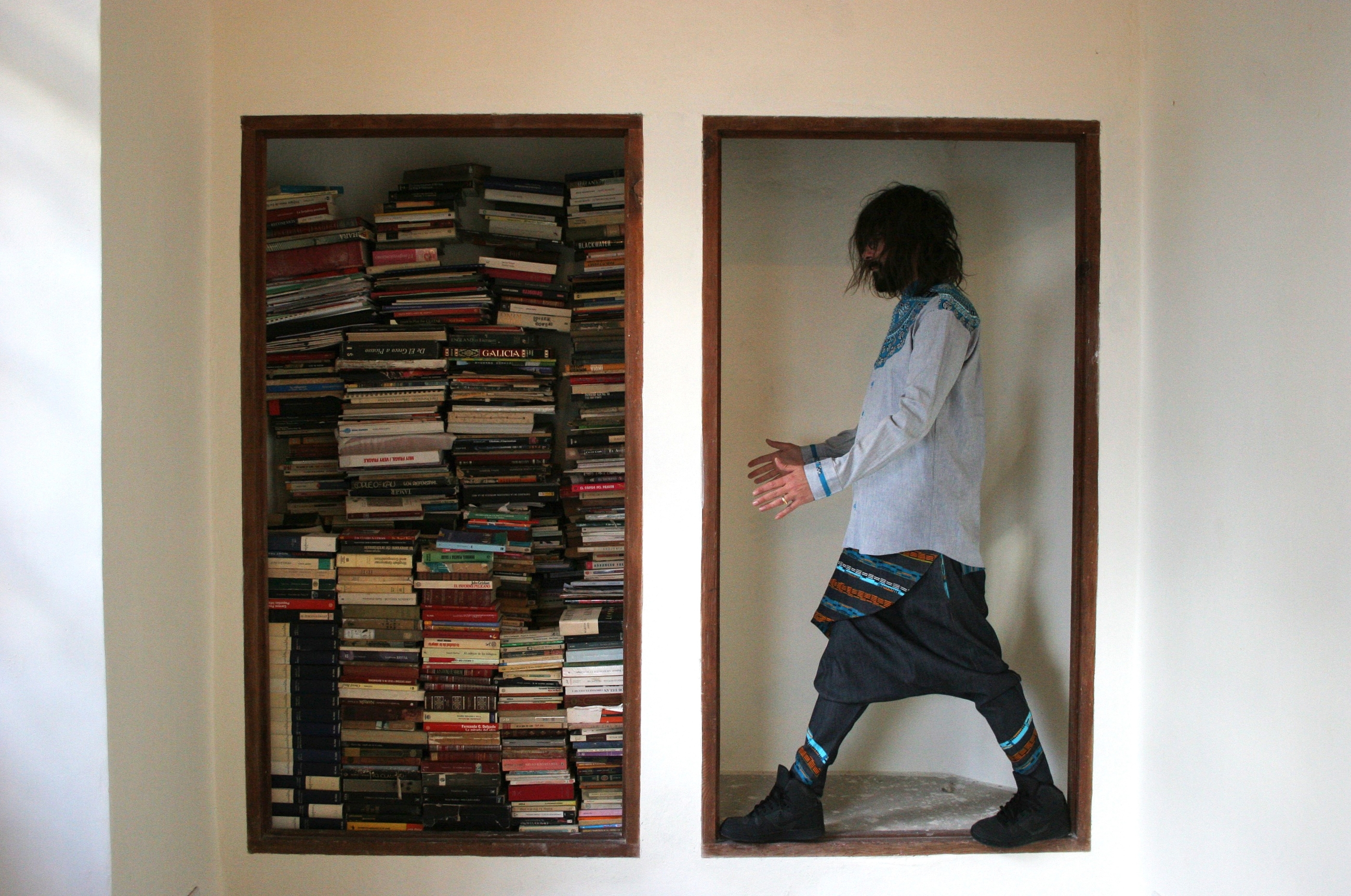

It isn’t hard to identify Farmaian by his theatrical style. He is dressed in a graphic patterned shirt with matching harem-styled trousers and jewellery - a style of Berber heritage that anchors our conversation.

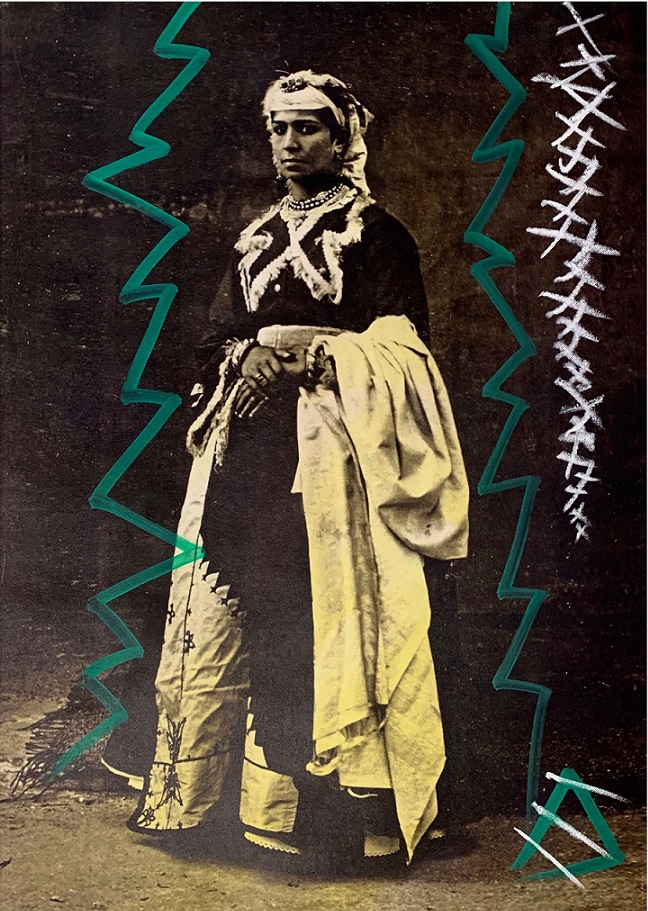

"She is the spirit and the figment for the continuity of trace," he says of a central portrait of a 1900s Berber woman weaver, inspired by his visit to the Berber Museum at Jardin Majorelle in Marrakech.

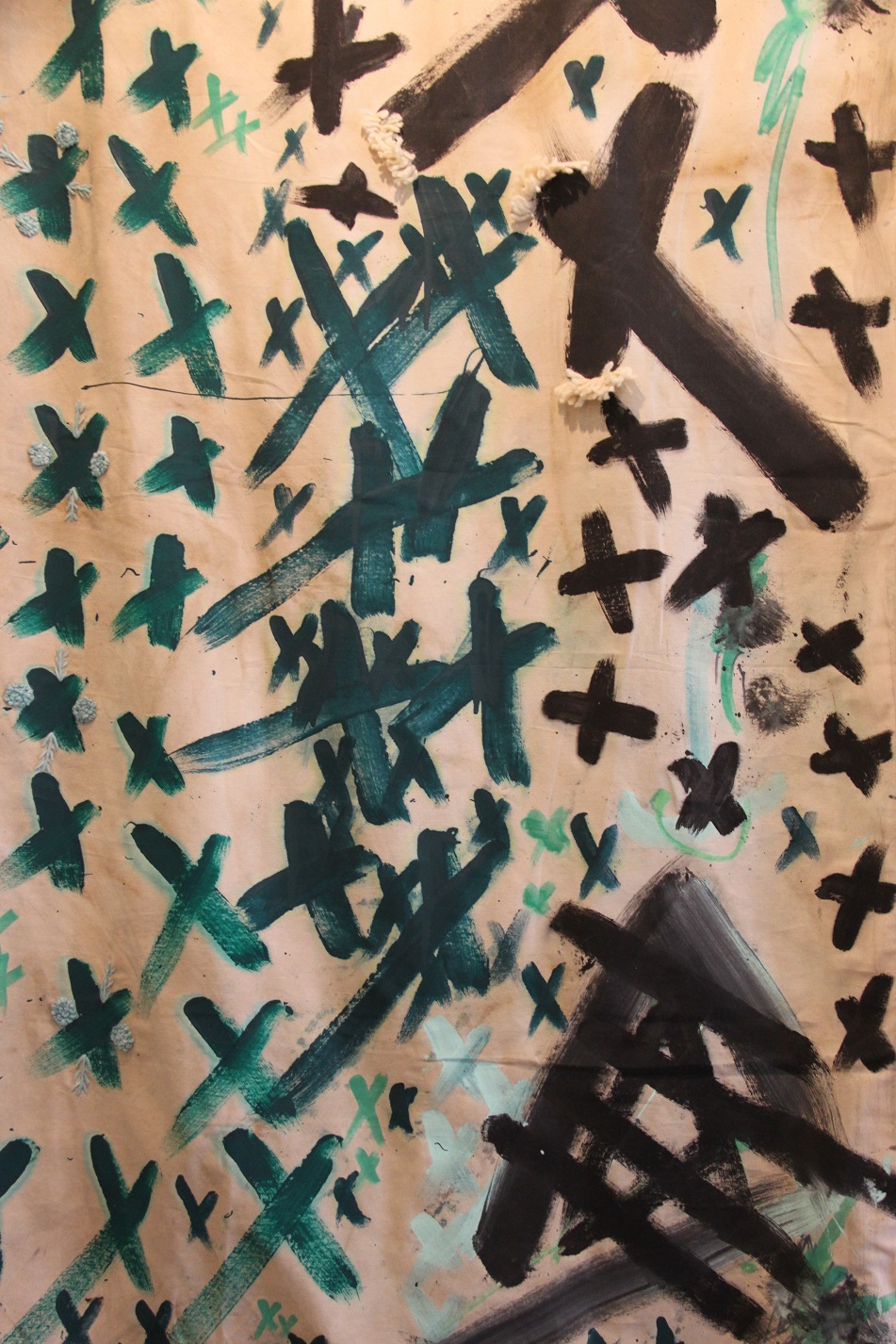

"Permanence of Trace" is typical of his approach, in that it interweaves the sacred symbols of Amazigh craftsmen from North Africa with his own Persian heritage. Berber tent fabrics and canvasses depict the ephemera of women weavers of North Africa alongside fibulas, rafters and crosses.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Amazighs, also called Berbers, are an ancient North African ethnic group and the name literally means "the free people". Inspired by their fortitude, creativity, rituals and traditions, Farmaian is not only questioning identity and heritage, but is keen to recover their ancient past.

One particularly relevant lesson from the Berbers is the unspoken central position of women in their way of life. “The Berbers are a women-led tribe who represent the sacred, the force. They are the creators,” he says, before adding: “Art is a sacred form of ceremony that is linked to God. Since 2000 years the same expression of art passed from one woman to the other throughout the times and this has come to us in the form of tattoos and rocks.”

Equally important is this association of ceremonies, rituals and imagination with earthly objects and nature, a relationship that can be read as a timely ecological message for a modern consumerist audience.

The Portrait of Berber Woman (oil pastel, acrylic marker on archival canvas print), though inconspicuous in size, is nonetheless sharp and imposing with distinctive crosses. “The crosses render a cosmogenic sense. There is cosmogony in Berber culture that comes from ancient Egypt and Greek culture,’ he explains. The triangle embodies fortune, fertility, abundance and protection.

Memories of Iran

The art also reflects his own early experiences between continents as a fugitive of the Islamic Revolution. These experiences bring a personal touch to his pre-occupation with tradition, remembrance and displacement. “Understand that we have gone through a process of displacement following the revolution in 1979,” he says.

The 40th anniversary of the Islamic revolution has brought back a lot of memories to Farmaian and his family outside of Iran. “During those times I suffered greatly after the revolution with my parents in the middle of a divorce.” Farmaian is grateful to King Hassan II of Morocco who protected him and his family from experiencing the horrors of contemporary exile.

As a descendant of the Qajar dynasty, which ruled Iran from 1794 to 1925, and in exile for nearly 40 years, Farmaian doesn’t feel he is the right person to discuss the situation back in Iran.

“You will have to ask people living in Iran. But if you take what’s happening there, the protests in the last few years and the dire situation the country is in because of the sanctions, people want change, but then again I don't know if it will happen,” he adds.

In fact, no one understands the “nomadic displacement of sorts” and the idea of “trace” better than Farmaian.

Trace is most famously associated with Jacques Derrida, who developed the concept in the 1960s to deconstruct art to its cultural, political and institutional contexts in their variety and difference, a radical departure from the Modernist movement of the first half of the 20th century which emphasised innovation in art, celebration of progressive forces, and a rejection of the cultures and traditions of the past.

Deconstructing Derrida

While Derrida used “trace” as a criticism of Modernism, Farmaian has appropriated the concept to invite the viewer to explore the history and variety of Berber culture through his use of authentic mythology and symbols.

His upcoming show “Decentralized” with Mana Contemporary in New York will feature three panels from “Poetry of Tribes”. Here his abstract unfinished impassioned brush strokes, vivid in colours and rhythmic function are as broad and wide as his determination to tell the story of belonging, separation and exile.

As a child he studied classical architecture, Greek classical culture, impressionism and Persian poetry with his grandfather. “He would teach me to draw ionic columns in the evening, just for fun. You get the drift.”

“My father familiarised me with a culture which I didn't know but definitely had a whiff of what I had missed growing up in Iran. Suddenly in a Felinian way Morocco became a mirror [a replacement] of a culture I had lost,” he reminisces.

From Attar of Nishapur, Rumi or Omar Khayyam to Charles Bukowski and Leo Tolstoy - his cross-cultural journey from adolescence has been punctuated by both the East and the West, Persian poets and philosophers, Russian, English and American literature. Not surprisingly, this leaves Farmaian to believe the mixture of cultures is the natural evolution of things, it is the future of the world.

In between sips of water, Farmaian scribbles notes into his copybook describing life on the road as a prism. “The advantage of a prism is it hits with multidirectional light. I believe at any rate who ever is against this natural evolution of things, it will be difficult. The tide of the world is going towards this direction.

“Those who believe nationalism is the answer are completely wrong in my point of view. I believe, and even if it goes through pain, similar to my family’s pain and suffering to lose what is yours, a richness awaits you on the other side.”

Graffiti and rock music

Whilst his journey into art has been anything but linear, painting was a constant since the age of 12. Post-impressionist artists like Vincent Van Gogh and Claude Monet were some of his earliest influences growing up in Paris. And this style is tangible in his series Summer at the Caspian, 2015, where Farmaian enmeshes family, pre-revolution Iran, emotions before and after exile, memories, past and the present.

“I grew up witnessing the street life of Paris doing graffiti in my late teens. I didn't last very long as I didn't like the anarchist ‘fuck the police’ atmosphere.” Farmaian swiftly returned to architecture, then graphic arts, and started experimenting with different forms on Super 8mm films.

As a pluralist, Farmaian finds himself closer to conceptual art, challenging his grandfather’s notion of form follows function. “Function follows form. The experiment is on form,” he insists. After working in graphic arts and indie film, which saw little funding, he turned to music and formed an indie alt rock band “Playground” in Paris.

Even today, he finds parallels of working on music and art strikingly similar. “The way you go through the processes of creativity is similar to the way you go through the processes of improvisation in music, and the specific types of music.

“You work on the same beat, give it a beat and you are jamming on an idea. You go from piece to piece in your project . You evolve, evaluate, get to a peak and end it.”

For his project 2020, Farmaian is keen to go beyond paint into monumental installation form, where he can use a multitude of mediums to create a conversation between sound, sculpture, paint, photography and film.

Farmaian divides his time between Marbella in Spain, New York and London. When it comes to calling any one place home, he invokes the German concept of ‘Heimat’. “It is the idea of home, and the idea of home is like a tent you can transport from one place to another, and make home a place wherever you go.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.