How the vulgarity of mahraganat taught me to accept my Egyptianess

My sister and I have little to nothing in common. A fashion stylist turned marketer for influencers, she moved to the US in 2002, seeking the American dream. Over the years, she converted to evangelicalism and adopted conservative politics, moving away from most things Egyptian.

Basic communication has always been a struggle, augmented by our disagreements on politics. Every year, an inevitable flare-up occurs, ignited by my intolerance towards her religious conservativism.

For years, we have tried to maintain civil communication but to no avail. That was until a few years ago, when out of nowhere we seemed to have finally found a common passion that paved the way for smoother communication: mahraganat music.

Mahraganat, which means "festivals" in Arabic, has caught on among the Egyptian and Arab diaspora, striking a chord with millennials who were won over by its catchy beats, amusing crudity, and sense of abandon.

While my sister’s enthusiastic embrace of American culture has blunted her affiliation with things Egyptian, the failure of the 2011 revolution and my subsequent withdrawal from local cultural life has had a similar impact on me.

The biggest gift mahraganat gave us is a sense of reconciliation with a culture we had shunned for our own different reasons. It is a portal into a world that briefly pacifies awareness of oppression, poverty and ugliness; an entertainment vehicle free from any governmental intervention or creed.

The establishment’s war on mahraganat

In what feels like deja vu, mahraganat has been making headlines in Egypt again, as the Egyptian Musicians Syndicate banned mahraganat singers from performing in public.

Armed with a decree passed by parliament in November, the syndicate has the authority to fine any facility that hires mahraganat singers and jail any unregistered recitalist who does not have a public performance licence.

Talk shows have allowed Hani Shaker, the head of the syndicate, and other members ample space to justify their position while not giving any space to the mahraganat singers to do the same.

Local media has overwhelmingly backed Shaker, with veteran journalists asserting the state’s right to elevate “public taste and protect the Egyptian ear from speech shenanigans”.

With the confidence of state patronage, Shaker went as far as saying whoever disagrees with the decision “does not love Egypt” and that “a dark force is attempting to distort and trivialise the Egyptian song with words that deviate from the core values and morality of the society, and promote violence and social disintegration".

Yet perhaps the most revealing statement in Shaker’s attacks on mahraganat is related to his defence of hip-hop, whose performers enjoy a more elevated status in the syndicate compared to the mahraganat singers.

In reference to Wegz, Egypt’s most popular rapper, Shaker stated that he considers him “a son” and that he shouldn’t be compared to the maharaganat performers because “he’s a college graduate”.

This is an escalation of the long-standing standoff between the syndicate, headed by the 68-year-old singer Shaker, and the young mahraganat performers: a battle rooted in class, professional jealously, and the regime’s insatiable desire for controlling public taste and enforcing its bourgeois mores.

The ban, in many ways, is one last desperate attempt by the syndicate to restore its diminished status, relying on coercion and opportunistic patriotism to silence voices that stray from what Shaker considers “good art".

While opposing voices from the entertainment community and public helped overrule the syndicate’s ban on mahraganat in recent years, the government now fully backs the syndicate in what appears to be the death blow to the public existence of maharaganat music in Egypt, at least in the foreseeable future.

A break from the mundane

The Egyptian music my generation grew up with was the homogenous staid pop of the likes of Amr Diab, Ehab Tawfik, Mohamed Fouad and Shaker himself. The lyrics were hollow, primarily centered on love, betrayal and heartbreak that my grunge generation found at best immaterial and at worst laughable.

Their music was stale and outmoded, devoid of any urgency. The sense of exhilaration and disarmingly naive sincerity of the best of pop was nowhere to be found in the Egyptian music of the late 1980s and 1990s. Simply put, the “good art” that Egyptian contemporary musicians of the time were producing was music my generation could not connect with.

The alternative local scene of the 1990s was dominated by heavy metal whose massive popularity was diffused by a media campaign that framed it as a satanist cult.

As electrifying as that scene was, it was largely targeted at upper-middle class English-speaking teens with the spending power that helped them purchase pricey electronic guitars and foreign records.

The flourishing independent scene in the early 2000s finally provided eclectic alternatives to mainstream music.

Cairokee, West El Balad, Eftikafast and Masar Egbari were among the many indie bands that progressively attracted a large following, eventually crossing over to the mainstream thanks to their genre fusion and socially-grounded lyrics.

Soon, electronic music began to attract a sizeable following, paving the way for hip-hop and ultimately mahraganat by the decade’s end.

The relative freedom of Mubarak’s final years and the availability of pirated software allowed aspiring musicians of the Cairo shantytown of Dar El Salam – the birthplace of mahraganat – to create a new and innately Egyptian genre that bore no resemblance to anything else produced at the time.

A voice for the poor

Distributed freely on YouTube, mahraganat was born out of the belly of poverty – an explosive charge that carried the desires and frustrations of millions of marginalised young people let down by the hollow promises of education and social justice.

Although recent, more popular mahraganat focuses on familiar themes of love and fear of heartache, some earlier songs dabbled with thorny politics such as imprisonment and destitution. Contempt for the police also featured heavily in some tunes, a motif that has ebbed and flowed over the past few years.

The quality of the music was varied but what it lacked in lofty production values, it made up for with a hybrid mixture of synthetic sounds that ranged from the languid to the imaginative.

The beats were irresistibly catchy; with rap-influenced lyrics rooted in colloquial speak; and unlike folk, the music was surprisingly melodic, combining traces of shaabi, minimal techno, hip-hop and pop. The sound of the mahraganat was edgier, fresher, and brasher than anything in both the mainstream and indie scene at the time.

By 2015, mahraganat was the most covered Arab music scene in the international press, with Rolling Stone dubbing it “Egypt’s musical revolution” in 2014. Early figures of the movement such as Sadat, Oka, and Ortega became overnight stars, sought by festivals and music venues across the world.

Locally, mahraganat shattered class barriers. The music has been ubiquitous, blaring from tuk-tuks and luxurious wedding parties alike. Music by Shaker and his cohorts, who never received international attention during their lengthy careers, are nowhere to be heard in public or private venues; the mahraganat, by comparison, is everywhere.

Make no mistake, mahraganat contains its fair share of misogyny (it is no different to hip-hop in that regard), while some of the music can be as derivative and languid as their mainstream counterparts. But these infirmities are by-products of the musicians’ environment – one governed by disorder, apathy towards education, and inherited rotten masculinity.

But even with its questionable themes, there was more authenticity, more truth in mahraganat than anything in the mainstream. The reality of the slums it has conveyed has been forbidden by the government to be shown in any popular art-form, especially in film and TV.

The world of the mahraganat is that of unemployment, unrequited love, financial struggles, abrupt arrests, violence, and, most incensing to the syndicate, drugs and alcohol.

The Egypt it portrays is one closer to the stories of Naguib Mahfouz than anything on film and TV.

In his culture study Pretentiousness: Why It Matters?, British critic Dan Fox writes: "Deviance is in the eye of the beholder. in the gap between one individual's baseline of acceptable behaviour and the actions of another. The conservative who brands someone a 'deviant' for their appearance or lifestyle choice is trying to maintain a particular set of rules in which they have an emotional investment."

In defence of ‘vulgarity’

The picture mahraganat paints of Egypt is of a nation neither the government nor the syndicate is willing to admit exists.

Contempt for mahraganat on the part of the middle-class supporters of Sisi’s government stems from self-denial: a denial that this is how the majority of the society is; that this is how young men speak, dress, think, and love.

The syndicate has consistently accused mahraganat of being “vulgar,” of sullying the public’s ear, of corrupting the youth, or promoting vile ideas and tearing up the moral fabric of society. But how do you define vulgarity to begin with? And what is the harm in vulgarity?

In his 1992 book, Carnival Culture, American professor, James B Twitchell, writes: "the vulgar is powerful because it takes very simple ideas very seriously, earnestly and energetically; that its predictability is strength; that derivation and repetition are signs of success; that it is authentically democratic and classless, and that it is infinitely tolerant, viciously cheap, and ultimately adaptive".

The vulgar is powerful because it takes very simple ideas very seriously, earnestly and energetically...

- James B. Twitchell, Carnival Culture

Vulgarity is what gives mahraganat its vitality and impetus; its force and relevancy. The genre is both a celebration of the willpower of the working class and a condemnation of the successive political systems that widened the gap between the rich and the poor.

Every facet of life in Egypt is governed and defined by class, and for once, the derided slum dwellers have found a way to let their voice be heard out loud. You may dislike the tawdriness of the music and the baseness of the lyrics, but you cannot deny the strength of its resonance.

Besides, references to drugs, alcohol and sex feature more heavily in syndicate-sanctioned rap and are not a novelty to “conservative” Egyptian society.

Explicit and implicit allusions to sex, drugs, and alcohol can be traced as far as the beginning of the 20th century in the songs of Sayed Darwish – composer of the Egyptian national anthem. Leila Nazmy, Karem Mahmoud, El Sheikh Imam and even Umm Kulthum herself – singers the syndicate regard as untouchable idols – have all sung in praise of this holy trinity of sin.

Eroticism has been an indispensable component of Egyptian classical music, an element Shaker seems to have forgotten.

‘Squashing’ faint acts of rebellion

The mahraganat sound has infiltrated every aspect of local entertainment, from advertisements and TV shows to sports events and political campaigns. Resistant to change and self-transformation, the entertainers of the 80s and 90s generation have been cast to the peripheries by both the market and the public.

Their campaign to curtail the success of mahraganat can only be interpreted as a desperate attempt by fading stars to maintain an importance that is no longer democratically justified.

Another layer to the government’s crusade against mahraganat is its association with the 2011 revolution.

In a recent interview, veteran composer Salah el-Sharnooby likened the mahraganat performers to “snakes that burst out of the swamps after 2011”. Popular TV host Amr Adeeb has also referenced 2011 and the agents who mobilised the youth at the time in his criticism of mahraganat.

Since attaining power, the Sisi regime has shut down every avenue of free expression, squashing faint acts of rebellion in different art forms to snuff out the possibility of another revolution.

Independent culture centres and music venues were closed; concerts by indie groups were cancelled; and lyrics censored. It was therefore only a matter of time before the state turned its attention towards a hugely popular music genre that has evaded policing - a genre it has struggled to control.

The mahraganat ban essentially remains a class contest, however. Listening to comments by Shaker and his like is to see a decaying middle class threatened by the smashing popularity of music that challenges their conformist aesthetics and self-serving moral codes.

In December, the syndicate announced that it asked YouTube to remove mahraganat clips, some of which have millions of views, while persuading Arab countries to take similar action.

#صورة_جديدة_للملف_الشخصي pic.twitter.com/dDoXo9yULE

— Hamo Bika (@HamoBika) May 17, 2020

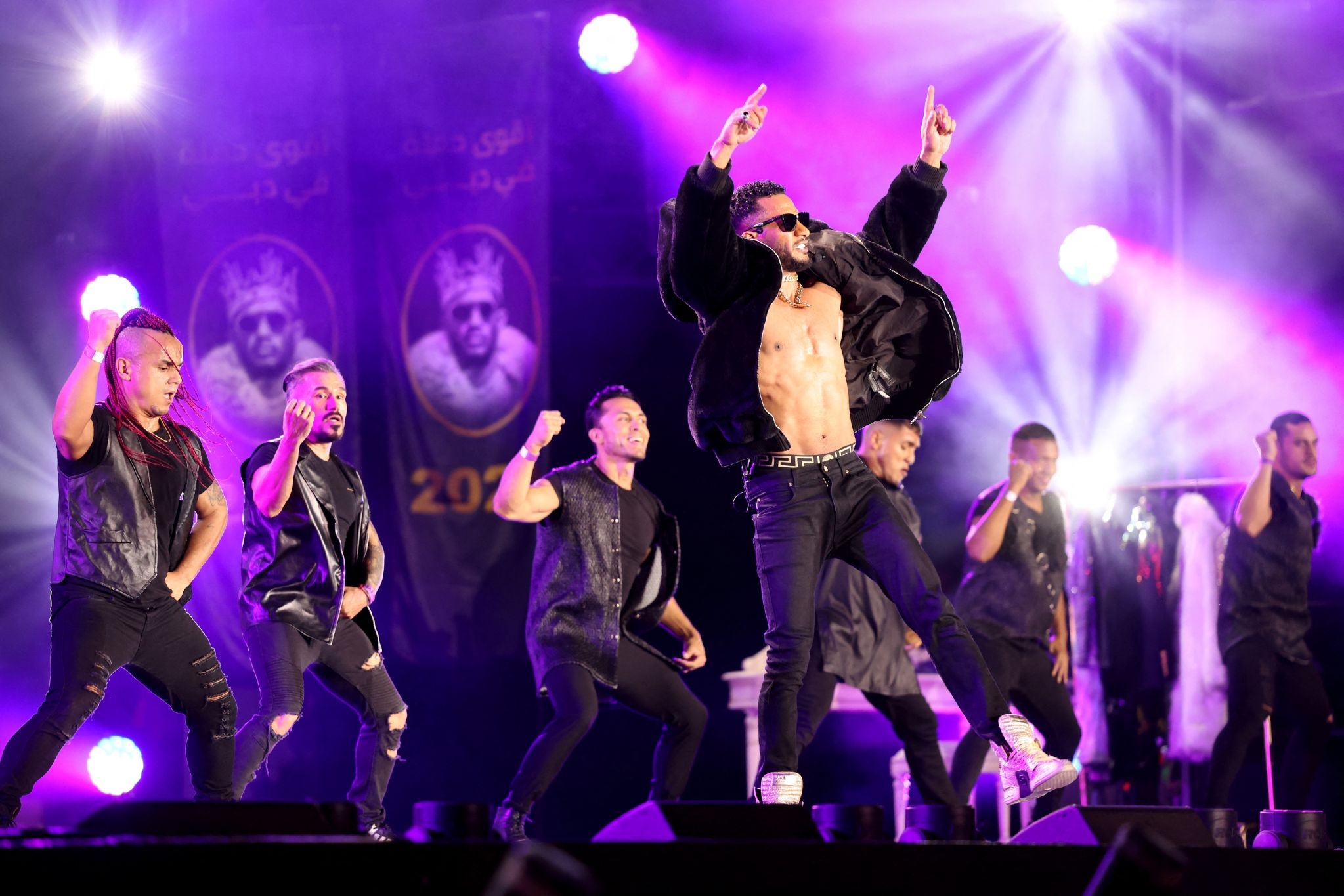

It has also fined male singers and threatened to suspend others for taking off their shirts on stage and “violating clothing conduct”.

Meanwhile, popular singer Hamo Bika, whose modest educational level and unrefined demeanor have been the subject of mockery by syndicate members and media commentators, rocked a series of sold-out concerts in Saudi Arabia where cheering audiences shouted for a recital of his hit song, Vodka & Chivas.

One of my most memorable recollections of the Berlin lockdown last year took place when I was taking a nocturnal walk in the mostly Arab and Turkish populated neighbourhood of Wedding.

A car swept past me out of nowhere, blasting Hassan Shakoush’s Bint El Giran, a popular mahraganat tune. Time and time again, a car playing Bint El Giran or another mahraganat song would pass me by, instantly driving me and my friends into a gleeful dance frenzy.

Mahraganat cannot be compared to the politically charged 80s rap of NWA and Public Enemy, nor does it possess the sophistication and heightened technicality of Arab hip-hop, but in giving millions of slum dwellers a voice, it accidentally became a thorn on the side of the government.

It presents a contrast to the elite’s fixation with projecting a falsely neat, clean image of the society it’s forcibly shaping, a society governed by the traditionalist, religious middle-class values of its leader.

Dancing to Bint El Giran in Berlin was revelling in the music’s insubordinate spirit, in its power to shatter class and ideological barriers.

The syndicate may continue to disallow mahraganat singers to perform in Egypt; it may eventually use its new powers to arrest a few performers for reasons it conjures up, and it will certainly go after its vocal critics.

By now though, the mahraganat force is too sturdy for any despotic regime to beat; its sound is impossible to mute. It will live, evolve and grow, and the people shall continue to dance in defiance.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.