The anonymous Baghdad satirist who gained a cult following in Iraq

In the chaotic autumn of 2005, a writer calling himself “Shalash the Iraqi” sat down at his computer and composed a darkly satiric dispatch about the state of his country.

When the finished text was published online, the anonymous author could not have expected that his writing would get much of a response in a country where, at the time, only a minority of people had internet access.

And yet, the author recently said during an email exchange with Middle East Eye, it was only a few days before his new writing persona “became a phenomenon that occupied public opinion".

The unnamed Baghdadi author continued to write and publish at a feverish pace through the rest of 2005 and most of 2006, attracting wide attention inside Iraq, before abruptly bringing his column - and the “Shalash” persona - to an end.

Now, two decades after the US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq, 70 of Shalash’s hundred-plus posts have been collected and translated into a vibrant English by Luke Leafgren.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

These genre-defying short works were published earlier in May by And Other Stories as Shalash the Iraqi.

As Kanan Makiya notes in his introduction to the book, there were a scant 25,000 Iraqi internet users in 2003. By 2007, a year after Shalash stopped publishing, there were still only an estimated 275,000 users in a nation of 28 million, according to a US report.

'It was a terrible thing for me to be influential in a way that I did not expect, and that I could not even have imagined'

- Shalash

Yet Iraqis, as Makiya writes, didn’t let a little thing like a lack of internet stop them from getting to know the relentlessly funny Shalash, whose high-energy, high-wire-act posts mocked everyone in Baghdad, but especially those in power.

“People were printing them out, copying them longhand, memorising them, talking about them, sharing them, telling and retelling them, plagiarising them, and bombarding Shalash with questions and opinions about them by way of the email address he always provided for his readers at the end of each post," Makiya writes.

Shalash’s posts raced through the gamut of genres, as though their author felt the need to make up for lost time by trying out every literary form possible in one short year.

There are magical-realist short stories, biting political essays, over-the-top satire, and all manner of linguistic inventions. Most of all, there is humour.

Sudden popularity

Shortly after he started publishing these dispatches, Shalash - whose real identity is still a secret - found himself overwhelmed by his sudden popularity.

His fans were not just ordinary Baghdadis; he also had admirers who were artists, writers, musicians, and politicians.

“It was a terrible thing for me,” he says, “to be influential in a way that I did not expect, and that I could not even have imagined. Readers turned Shalash into their conscience and their exclusive voice.”

Shalash continued writing his bitingly funny posts through November 2006, and then stopped.

'I lived those years under cover, writing under a pseudonym and afraid of violence at the hands of the same people I had loved since I was born'

- Shalash

But although his posts stopped coming and other writers stepped in to satirise Iraq’s political class, Shalash remained a part of Iraqi public consciousness.

Both Shalash and translator Luke Leafgren expressed some anxiety about the challenges of bringing this vernacular writing, which is dense with references to Iraqi public figures and events, into English.

In his introduction, Makiya notes that Shalash’s work is “difficult at times for even non-Iraqi Arabs to follow".

In our exchange, Shalash went further, saying that because he used a hyper-local, working-class vernacular, “even Iraqi readers had difficulty understanding some of Shalash’s writing".

Leafgren notes, in his afterword, that while he didn’t often interrupt Shalash’s fast-paced patter with footnotes, he did add the occasional explanatory gloss.

It's true: the non-Iraqi reader is met with challenges while navigating this collection of short texts.

The difficulties are not with Luke Leafgren’s translation, which delightfully recreates the original’s winking, louche, and linguistically inventive tone. But the reader still must come to grips with all these new places (primarily in Thawra City), his cast of characters (neighbours, politicians, religious leaders), and the events of 2005 and 2006 (the proliferation of satellite TV, violence, and the endless shenanigans of politicians).

But as the reader moves from dispatch to dispatch, they slowly learn their way around Thawra City, the suburb of Baghdad that sees most of the action. And there is a lot of action: the period in which Shalash wrote was just after Iraq voted to approve a new constitution, soon after the Iraqi Transitional Government took power, and as elections were held for the first post-Saddam permanent government in May 2006.

“And if you should find any of that a little confusing,” Shalash writes in his introduction, penned some 16 years after his original columns, “well, think of how we must have felt - especially when there were multitudes of political parties, ethnic groups, and religious leaders vying for control of the territory and its natural resources.”

The English-language reader is thus in some ways in the same position as the Iraqi in 2005 and 2006, trying to make sense of this strange new landscape, with Shalash as their guide.

Making fun of (almost) everyone

Many of Shalash’s dispatches read like vignettes, in which we sit down with the characters in his neighbourhood and listen to them argue about current events. But others, like The Privatization of Da’bul’s Oil, work like full-length short stories.

In that short work, published in November 2005, oil is discovered in a 10-year-old’s urine. Soon after, a struggle erupts to control this valuable natural resource.

At first, it is only Da’bul’s family and neighbours who take advantage of the boy’s remarkable wastewater.

And little Da’bul doesn’t mind: "Da’bul found filling their cans to be an entertaining game, one that restored the psychological balance he had lost on account of long neglect by his mother and the rest of his relatives. He began working vivaciously and cheerfully to meet the needs of the block’s residents, who were overjoyed at their access to this miraculous child, the solution to one of their most complicated problems, which even our illustrious Minister of Oil, Ibrahim Bahr al-Uloom, hasn’t been able to solve with all the degrees he brought back from London.”

This tenuous balance is upset when one of Shalash’s regular characters, Khanjar, arrives to exploit the situation, buying a percentage of the yield from Da’bul’s bladder.

At this, the family sees they have a lot to gain - or lose - and the maternal and paternal uncles begin to argue over who has a greater right to the boy’s bladder.

The story rises to new levels of absurdity when we learn the maternal uncles are members of the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution, while the paternal uncles are in the Sadrist movement.

The dispute doesn’t stay merely national, either. “With the Americans now involved, international corporate interests came in to study the reserves hidden in Da’bul’s bladder, with Halliburton’s report stating, ‘The quantities discovered reach approximately one hundred and twelve billion barrels. Including the probable reserves, Da’bul holds claim to being the number one producer in the world.’”

For better or worse, in this short story, it’s Da’bul himself who gets the last word.

Other dispatches in the collection make fun of the hypocrisies of political language (as in Our Chaldo-Assyrian Brothers), social and gender norms (as in The Hajji’s Third Time Through Puberty and The Political Process on Our Block), political corruption (as in Our Tribe Reaps the Election Harvest), difficulties with electricity and other public services (as in The Lake of Light: A Long Story), and more.

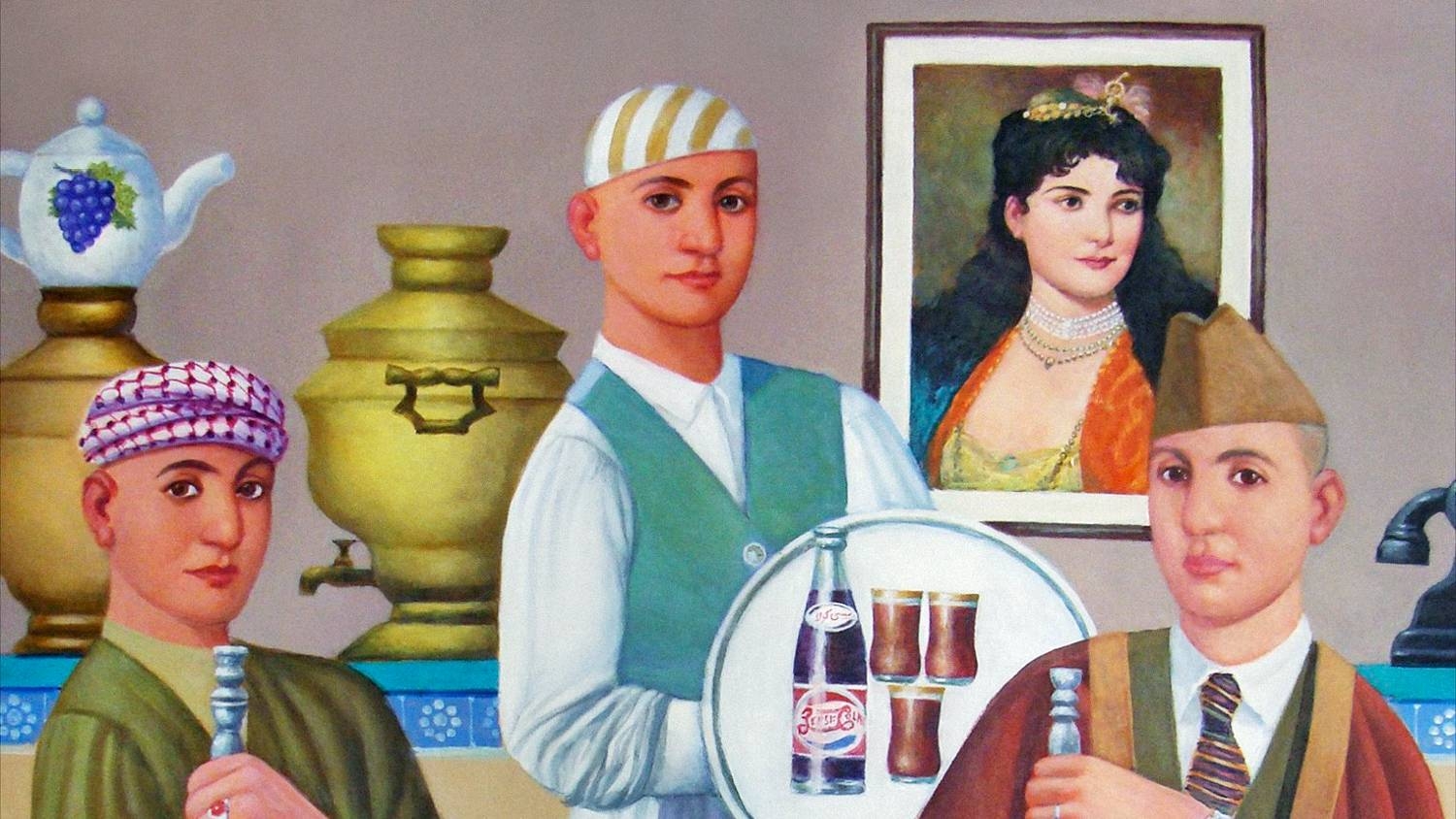

The dispatches are often dialogue-heavy, with Shalash strolling through his neighbourhood and talking to his fellow citizens. One can imagine his fans, in 2005 and 2006, wondering if one of the young men at their local cafe or kiosk might be the popular writer known as Shalash.

Yet it was necessary then, and remains necessary now, for the writer known as Shalash to keep his identity hidden. As he writes at the end of his introduction: “And so I lived those first years under cover, writing under a pseudonym and afraid of violence at the hands of the same people I had loved since I was born.”

This highlights one of the most joyous things about the "Shalash” writings: how his writings shift rapidly between violence and love, but also how - when mocking his fellow Iraqis - he remains so tender toward each and every one of them. Well, nearly each and every one.

Shalash the Iraqi is translated by Luke Leafgren and published by And Other Stories

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.