Yildiz Camii: Istanbul's last sultanic mosque

Contemporary imaginings of Istanbul are plenty. From Orhan Pamuk’s depictions of the Nisantasi district, to James Baldwin’s writings after he left the US and settled in the city, seeking refuge from racism.

For these authors and others, Istanbul is "one of those cities" - a melting pot and an able host, one with many characters, peoples and identities.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Theirs is the Istanbul of coffee houses, meyhane (watering holes), nightclubs and meditations dreamt up gazing over vistas of the Bosphorus or Golden Horn.

Yet in these accounts of Istanbul, rooted firmly in the post-Ottoman Republican era, the city’s mosques play the part of an obliging supporting character at best, and the haggard remnant of an intrusive and overbearing past at worst.

In his ode to the city, Istanbul: Memories and the City, Pamuk describes “burned out” bulbs spelling out holy messages between the minarets of mosques and the “blackened” posters covering their walls.

When Pamuk, the Nobel laureate, decides to paint, he chooses a back street in Beyoglu, Tarlabasi or Cihangir, where there are “very few mosques or minarets”.

“This is indeed a city moving westward,” he declares later.

The Islamic city

When reading Pamuk, it’s easy to forget the city’s mosques were once far more central to its identity.

Istanbul’s mosques were not mere places of worship, but hubs of social interaction towards which scholars, students, merchants and men of politics gravitated.

Once an Eastern Roman city, Istanbul became the centre of the Ottoman sultanate, and thus became the sultanic city; an Islamic city, which would later be known for its thousand mosques.

When Fatih Sultan Mehmet II conquered Constantinople in 1453, he went on an ambitious drive to Islamise the city, supplanting its Eastern Roman past, most notably by converting the Hagia Sophia into a mosque. The building of ornate places of worship subsequently became a way of cementing the Ottoman Islamic legacy onto the city’s landscape for successive sultans.

By the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II (1876-1909), Istanbul was not simply an Islamic city but the Islamic city of the Muslim world, the city of the Ottoman caliphate and 400 years of Ottoman tradition.

The 19th century saw the Ottomans increasingly leaning on the office of the caliphate to cement their Islamic authority against the rise of nationalist currents. The city's mosques took on a renewed transcendent symbolism within this context, as the Ottoman state sought to assert its supremacy with fresh vigour.

In the past, mosques like the Hagia Sophia, the Sultan Ahmed, the Fatih and the Suleymaniye, were much more than places of worship and gathering, but emblems of Ottoman rule and power.

Such was the importance of these great architectural feats that it was they that gave their name to the areas they were located in and not the other way round, as is the case even with upscale districts such as Tesvikiye and Cihangir - both named after mosques.

But while these monumental structures have their unique histories and are regular stops for tourists and locals alike, it is the last sultanic mosque built in Istanbul that is largely absent in the collective imagination.

It was a mosque that was supposed to usher in a new dawn for the Ottomans, the mosque of Sultan Abdulhamid II, the Yildiz Hamidiye Camii (Star mosque).

Yildiz a symbol of a new imagination

Faced with territorial losses, outpaced in wealth and technology by its western counterparts and dealing with rising nationalist movements among non-Turkic subjects, the Ottoman authorities in the 19th century sought to rejuvenate the empire with a new unifying ideology: one that was rooted in Islam, was accepting of modernity and the diversity of the empire, and one in which an acknowledgement of Ottoman authority was absolute.

This effort would reach a climax during the Hamidian period - named for Abdulhamid II - where ideas of the modern were juxtaposed with Ottoman Islamic traditions.

Such ideals were imbued into the fabric of late Ottoman Istanbul and nothing represents their culmination more than the Yildiz mosque.

The house of worship was an extension of Ottoman attempts to establish an indigenous architectural style from 1873 onwards. Known as the Usul-i Mimari-yi Osmani (the Principles of Ottoman Architecture), the form was ostensibly rooted in classical Ottoman and Islamic tradition and yet was equally influenced by popular orientalist artistic styles from western Europe.

Under the stewardship of the Armenian Balyan family, an array of buildings and mosques were built all over the city to mark this new turn.

Mosques such as the Yeni Abdulmecid mosque in Ortakoy, the Pertevniyal Valide mosque in Aksaray and the Tesvikiye mosque in the district of Nisantasi are just some of the structures built during this period. One could say the Yildiz mosque was the apex of this trend.

Splendour and prestige

Completed in 1886, the Yildiz mosque - officially known as the Hamidiye mosque - took two years to complete. The order to construct this innovative piece of architecture was handed to the chief state architect, Sarkis Balyan, who employed the Armenian architect Dikran Kalfa (Jüberian) to assist him.

The mosque has no real definitive style but we can observe that the exterior used a unique neo-Gothic facade that was Ottomanised, and the interior used Andalusian-influenced Moorish styles, which had become popular with Ottoman Muslim elites at the time and could also be seen in many other late interior designs.

Its interior is beautifully painted, and crowned with a large chandelier sent as a gift by Kaiser Wilhelm II. The mosque’s dome is bright blue on the inside and painted with golden stars and a Quranic inscription from Surah Ikhlas by Ebuzziya Tevfik Bey.

There are a host of distinct calligraphic styles on display, marking it as distinct from other Ottoman mosques. Notably, verses from Surah al-Mulk along the top wall were written in a Kufic script, originating in Iraq, by the famed calligrapher Abdulletif Efendi.

Another unique feature of the mosque is the wooden lattices made from cedarwood, which were handcrafted by Sultan Abdulhamid himself, a keen carpenter. These took their inspiration from the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, and are in addition to the lectern, which was also made by the Ottoman ruler.

In many ways the mosque can be seen as an insight into the way the Hamidian state imagined itself on a global scale: a state that straddled three continents - Europe, Asia and Africa; a state which saw itself as both modern and attached to is transforming tradition; but more importantly, a global power.

The Yildiz mosque was the symbol of Abdulhamid’s vision of the Ottoman state as the modern imperial caliphate and a mosque of great splendour and prestige.

A monument of the famous mosque was erected in Marjeh Square, Damascus, as the Hamidian state attempted to foster the notion of unity between its Arab subjects and the imperial centre. Yildiz mosque, by virtue of its diverse artistic and architectural influences, was therefore intended as a statement on the Islamic ideal of brotherhood between different peoples.

Pomp and ceremony

On its inauguration, the building comfortably took up its role as a sultanic mosque, drawing pomp in line with its imperial importance.

Rarely, if ever, did the masses see the sultan besides his weekly visits to Yildiz for the selamlik (Friday prayers).

Foreign dignitaries who attended the events would describe the spectacle of the sultan’s arrival, with excited crowds waiting in anticipation and then greeting the ruler in awe.

The occasion had an importance beyond the celebration of imperial regality - the Friday prayer had a distinct role in strengthening the image of the sultan in the eyes of Muslims around the world. The reading of the Friday sermon in the sultan’s name was a part of the ritual of establishing the legitimacy of Abdulhamid II and the Ottomans as caliphs to all Muslims.

While Ottoman sultans in the past would perform their Friday prayers in Hagia Sophia, Suleymaniye or Sultan Ahmed Mosque, during the Hamidian period they were performed at Yildiz.

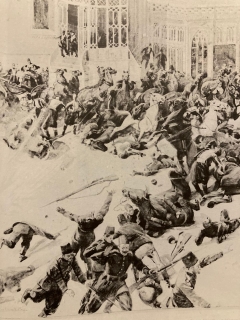

But the history of the mosque is notable for more than just the sultan’s ceremonial Friday prayer entrance. The building was also the site of one of the most dramatic and infamous episodes of Abdulhamid’s reign - an assassination attempt on the sultan by Armenian revolutionaries belonging to the Dashnak organisation on 21 July 1905.

The attempt at regicide, which involved a number of conspirators, saw an explosive-laden capsule placed under the carriage, which the sultan used to travel to the mosque.

Everything was going according to plan for the plotters until the sultan chose to spend some time after the prayer talking to the Sheikh-ul-Islam, the most senior Islamic jurist in the Ottoman state. The conversation caused a rather fortuitous delay for the monarch, which ended up saving his life. Others were less fortunate, with 26 killed and dozens more injured, as well as serious damage to the outer section of the mosque and its clock tower.

The mosque survived Abdulhamid’s overthrow by the Young Turks in 1909 and continued to be the main sultanic mosque of the city during the First World War, with both Sultan Mehmed Reshad (Mehmet V) and Sultan Vahdettin (Mehmet VI) offering Friday prayers there.

By surviving his own reign, the mosque came to embody what Abdulhamid hoped it would symbolise: a structure that held firm to the sultanic tradition and which was a visual symbol of the Ottoman state. In a short period, it had become one of Istanbul’s most iconic mosques. That was until the collapse of the empire.

The Turkish Republic and the neglect of the sultanic heritage

In the years after the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1924, Istanbul saw its fortunes decline as the capital of the new state of Turkey was moved to Ankara.

The city’s many mosques, including Yildiz, were neglected as the rulers of the new state sought to prioritise modernisation along western lines to the detriment of the Islamic past under the Ottomans.

For many Ottoman monuments, this at times meant demolition to make way for new development projects and at other times neglect through lack of maintenance.

Some decisions taken during this period remain contentious among Turks to this day. These include the conversion of the Hagia Sophia mosque into a museum, a decision that was reversed in 2020. There were even reports that officials were discussing the conversion of the Sultan Ahmet mosque (also known as the Blue Mosque) into an art gallery.

For Yildiz, the new era meant a period of decline, as much of its surrounding neighbourhoods underwent urban renewal.

From 1924 onwards, the French urban designer Henri Prost was enlisted to help redesign Istanbul.

The architect, who had previously worked for the French in Algeria, embarked on an ambitious but controversial campaign of redevelopment.

It was decided that large roads and streets would be created and, to make way, houses and Ottoman mosques would need to be cleared. The Besiktas area where Yildiz is located, was heavily transformed, with the mosque becoming virtually isolated on top of the hill.

It wasn’t until the two-party period after the Second World War that the government of Adnan Menderes recognised that Istanbul needed investment after much neglect.

Menderes during his years in power had attempted to appease Muslim sentiment by once again allowing the recital of the Adhan in Arabic, which had until then been banned. The Democrat Party leader also refurbished many mosques and built the first mosque in Istanbul since Yildiz, in Sisli in 1949, a whole 63 years later.

This new mosque was built in the tradition of 16th-17th century Ottoman style, bypassing the Usul-i Mimari-yi Osmani trend institutionalised in 1870.

Despite these nods to Turkey’s Ottoman heritage and a less conspicuous ideological motive than his predecessors, urban transformation policies under Menderes continued to relegate the significance of mosques such as Yildiz.

Development was the mantra of the day, and development projects continued along the lines of western modernisation with the city of Istanbul going through a significant transformation.

It wasn’t until the coming to power of the AK Party in the 2000s that moves to renovate many of Istanbul’s mosques became a priority. However, even in the AK Party period there have been continued tensions between the impulse to develop neighbourhoods and preserve historic monuments.

In the eyes of the preservationists, the ghost of urban development laid out by Prost continues to misshape the once imperial city.

In 2017, after four years of renovation, the Yildiz mosque was opened to the public in a refurbished state.

Since then, many other mosques have been built across the city, but none in the style of Yildiz. What was once hoped to herald a new epoch for Ottoman culture has instead become a historic architectural anomaly. The Hamidian mosque still escapes the collective imaginations of today’s worshippers.

State history has a unique way of facilitating what ought to be remembered and forgotten. The memory, or lack of, of Yildiz is proof of this.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.