Muqarnas: Honeycomb architecture that touches the heavens

From Spain's Alhambra, to Bosnia's Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque and Iran's Hasht Behesht Palace, the interior domes of many of the striking mosques and palaces across the Middle East and beyond feature a "honeycomb-like vaulting": this exclusive design has a name of its own – muqarnas.

This centuries-old style of architectural grandeur may adorn a building for purely aesthetic reasons, creating a smooth decorative zone that transitions between the bare walls and the ceiling of a building. But it can also serve a purpose in structural design - as load-bearing formations - with the earliest examples found in Mesopotamia.

Historically, muqarnas grew in their decorative use some time in the 12th century, during Islam's golden age, when Muslims made significant advancements in architecture, mathematics, science and the arts.

The concave structures are not sanctioned just for domes. They can also be found beautifying half-dome entrances as well as iwans - a rectangular space that serves as an entrance into a mosque from the courtyard - and the mihrab, a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the direction of prayer for Muslims.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Structural differences

There are two distinct forms of design: the North African-Middle Eastern and the Persian, where muqarnas are known as ahoopay. Within these forms, there are many styles based on different shapes such as squares, triangles, or assemblies of surface-decorated panels resembling pole table patterns.

The origin is still debated, but most sources say muqarnas are an evolution of the squinch - a rounding of corners in the upper angles of a square room allowing for the creation of a dome. The earliest example can be found in ancient Persia under the Sasanian Empire (224 to 651 AD).

The first forms of recognisable muqarnas were found in 10th-century architecture near the northeastern Iranian city of Nishapur, and also in Samarkand, in modern-day Uzbekistan.

As trade routes developed and as Islam flourished, so did the spreading of ideas - including architectural ones. Muqarnas can now be found in many notable historical and some modern buildings.

They can either be carved into the structure of a wall and ceiling, or they can be added on and hung purely as a decorative surface. This is often difficult for the untrained eye to differentiate.

Muqarnas differ based on the location

+ Show - HideMurqarnas can be made of brick, stone, stucco, or wood, and are sometimes clad with tiles or plaster. The size, shape, composition and use depend greatly on the region they are found:

- Muqarnas found in the West are often more intricate and creative as they developed in a time when regulation was less rigorous. They are often made of stucco due to an abundance of natural clay in the region.

- In Syria and Turkey, muqarnas developed under stricter rules and are also mainly constructed out of marble and stone, so they tend to be larger and less intricate.

- Stone is popular in Egypt, as hot weather and harsh desert winds can greatly wear down weaker materials like stucco.

- In other parts of North Africa, and in Iran, Iraq and Pakistan, muqarnas are built with bricks or covered in plaster and colourfully painted with ornate patterns.

The most distinctive form of muqarnas is the honeycomb structure, which can either seem impossibly intricate or seemingly simple - both results of a skillful combination of mathematics and art.

Middle East Eye has collated images of some of these intricate structures from ancient and modern architecture.

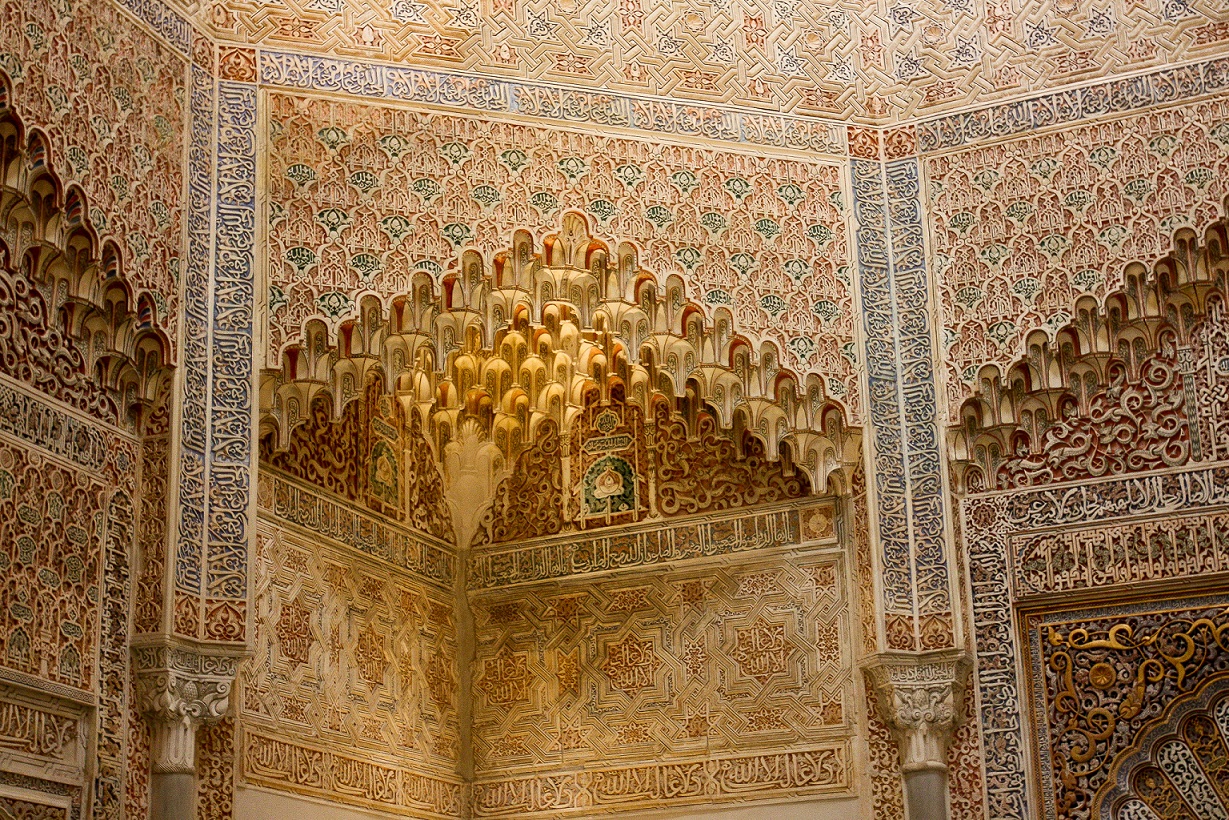

Alhambra Palace

Location: Granada, Spain

Date completed: Mid-13th century (Nasrid dynasty era), but renovated several times since

Described by Moorish poets as “pearls set in emeralds”, the Alhambra was the royal palace of various Muslim dynasties in Islamic Spain that was set on top of a hill surrounded by forests.

The palace and fortress are decorated throughout with geometrical patterns in an Arabesque setting with fine detailed muqarnas incorporating Quranic verses and names of sultans. Interestingly, pseudo-Arabic - an unintelligible Arabic script made to mimic Arabic text - was also added as decoration to parts of the palace during its many renovations.

Gateway into Old Cairo

Location: Cairo, Egypt

Date completed: 12th century (Bahri Mamluk era)

Old Cairo was once a walled city with many entrances and exit points, with smaller gateways and doors separating quarters between areas. The stone muqarnas seen above doorways have come to be known as "Cairo style" and are a prominent design feature in most post-Fatimid work, especially those employed by the Mamluks, a dynasty led by slaves who converted to Islam and became kings in the 12th century.

Unlike their elegant and finer Persian counterparts, the Cairo style muqarnas are much larger, usually built out of stone, and are concentrated in a limited space. They easily interconnect into the walls around them, which allows for a stronger structure in this earthquake-prone region of the world.

Al-Rifa’i Mosque

Location: Cairo, Egypt

Date completed: 1912 (Ottoman era)

The Al-Rifa'i Mosque is a modern structure that was built in 1912 and stands next to the historical Mosque-Madrassa of Sultan Hassan. The resemblance of both mosques in style and grandeur was an attempt by the rulers of Egypt at the time to associate themselves with the glory of the Mamluk dynasty.

It is also worth noting, though not easily visible, that the muqarnas have stalactites - hanging rounded ornaments - a design feature usually seen in Ottoman architecture, but also present in Egypt as a remnant of the 300-year Ottoman rule.

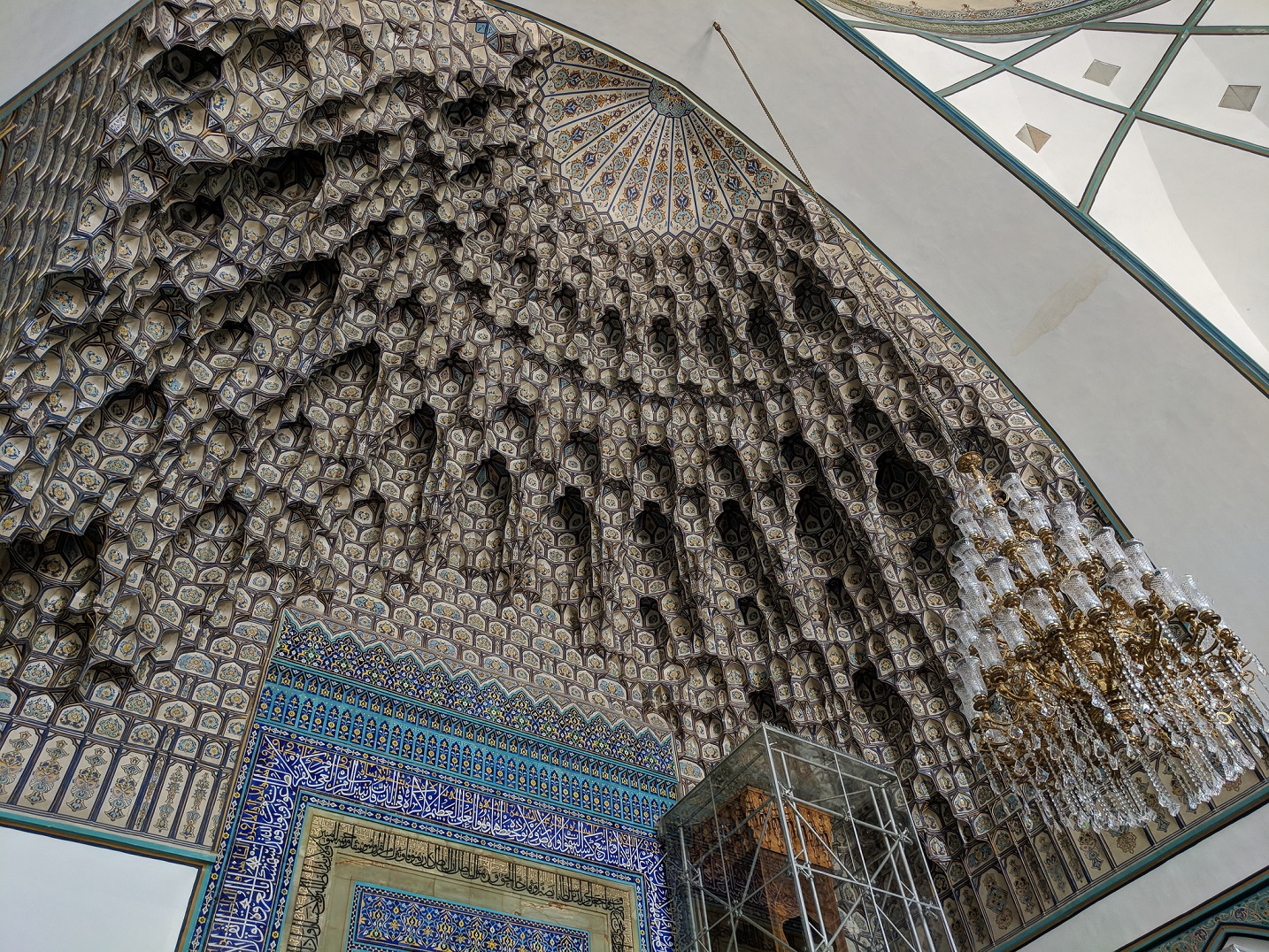

Jomhoori Eslami, Shrine of Imam Reza

Location: Mashhad, Iran

Date completed: 821 (Tahirid era)

The Jomhoori Eslami represents two distinctive features of Persian design – muqarnas and rasmi-bandi.

One part of the iwan (rectangular hall or space) features muqarnas, with the rest composed of rasmi-bandi, structures similar to spoke-wheel roofs. These forms demonstrate the geometry skills needed to be able to fill in space.

It is highly unusual, if not near impossible, to find traditional tile-cutting techniques used in the construction of modern-day muqarnas in Iran. Most are computer designed and laser cut to achieve the perfect fit, but they continue to impress visitors and worshippers, as Persian architecture has evolved but not departed from the genius of mosque design.

Goharshad Mosque

Location: Mashhad, Iran

Date completed: 1418 (Timurid dynasty era)

Influenced by Samarkand architecture, many parts of the mosque itself were rebuilt between the 1950s and 1970s.

The muqarnas behind and above the central mihrab are incredibly complex. They are not mirrored and gradually become smaller as they get closer to the ceiling. Made of plaster, they are painted with floral designs in navy blue, gold, and turquoise. Given the restorative work, it is highly unlikely these muqarnas are original Timurid.

Today the mosque is part of the larger complex of the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad and serves as one of the central places where congregational prayers are led.

Hasht Behesht Palace

Location: Isfahan, Iran

Date completed: 1669 (Safavid era)

Built in the 17th century, this private pavilion was built by Suleiman I, the eighth Shah of the Safavid Empire. The Safavid’s were renowned for their patronage to the arts and the development of a rich architectural style that today is considered to be the best example of Persian and Islamic art.

Unlike most Persian architecture where muqarnas are found at the entrance of a building, here they take a "pole table" style to fill the empty space below the dome. The wide flat base of the outer muqarnas are decorated with floral and Arabesque patterns, a reference and repeated theme in Persian art alluding to the highest heavens.

Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque

Location: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Date completed: 1530 (Ottoman era)

Built and designed in the 16th century by Adzem Esir Ali, a Persian from Tabriz who was the chief architect during the Ottoman Empire. The Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque is the largest mosque in Bosnia and Herzegovina and is seen as the most important piece of architecture from Ottoman rule in the Balkans.

The main entrance is decked with muqarnas that resemble a style that has come to be known as the "Sinan style", after the Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan (1490-1588).

The mosque was damaged during the Siege of Sarajevo in 1996, but reconstruction work started immediately after the war ended, signifying the importance of this centre for prayer.

Badshahi Mosque

Location: Lahore, Pakistan

Date completed: 1671 (Mughal era)

The Badshahi Mosque, or "Imperial Mosque", is a Mughal era structure in Lahore, the capital of Pakistan’s Punjab province. Built by Emperor Aurangzeb in 1671, it is said to be the most iconic mosque in the country.

Lahore was once a gateway to Persia and began to embody the region's distinct style in its own architecture. The Badshahi Mosque is built from red sandstone with white marble inlays and also features "pole table" style muqarnas that are almost identical to the ones found in mosques and traditional houses in Kashan.

Although none of the mosque's original artwork has survived, recent restorations in 2008 imported red stone from the Indian state of Rajasthan, the original Mughal source of this colourful material.

Wazir Khan Mosque

Location: Lahore, Pakistan

Date completed: 1641 (Mughal era)

The Wazir Khan Mosque is the Taj Mahal’s lesser-known cousin, but it is equally as stunning in design. The Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan was born in Lahore but died in Agra where he built the Taj Mahal to immortalise his wife Mumtaz Mahal. He also commissioned the Wazir Khan Mosque in the city of his birth.

It features brick muqarnas in most of its iwans and is decorated with square latticework and adorned with the names of the first four caliphs of Sunni Islam: Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali.

Muqarnas Glossary

+ Show - HideIwan - a rectangular space that serves as an entrance into a mosque from a courtyard

Mihrab - a niche in mosque wall that indicates the direction of prayer for Muslim

Squinch - a rounding of corners in the upper angles of a square room, allowing the creation of a dome

Fresco – a type of mural painted onto a wet plastered wall, as the plaster dries, so does the painting

Ablaq stonework – alternating rows of dark and light stonework, often found in Cairo and Damascus

Kashi-kari - originating from Kashan, Iran it’s the traditional glazed form of mosaic art that has decorated tiles

Rasmi-bandi - distinctive and original Persian patterns in traditional architecture providing ceiling coverage

Pendentive formation – triangular structures that come together to form a circular base

Lattice work: interlacing strips of material forming a lattice

Arabesque: ornamental design consisting of intertwined flowing lines

If you've spotted stunning muqarnas decorating a mosque or building - please send us your photos by tagging us on Twitter or Instagram and using the hashtag #MuqarnasMEE

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.