‘It will never be home’: Artist Sandra Watfa on Palestine, genocide and growing up in England

The door opens to a bundle of curly, silver hair. Wearing a black hoodie and leggings, Sandra Watfa offers an inviting smile as she clears the entrance to her London home.

Inside, the aura is one of purposeful zen. Ocean blue walls and patterned cushions evoke a sense of longing for the Levantine coast.

“I was born in Lebanon by the sea,” says Watfa, about the palette. “I didn’t know anything other than that.”

She brings over a white mug patterned with tiny Palestinian flags at its base. A plate of baklava and ginger biscuits dresses the table.

“Growing up in a Palestinian family, you begin to understand the repercussions of being in a country that is not your own,” she says.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Watfa’s parents fled Akka during the Nakba of 1948, which saw the Zionist dispossession of Palestinian land to establish the Israeli state.

With the family having found refuge in Lebanon, where the artist was born, the onset of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975 led to a second exodus.

“We ended up in Greece, which oddly enough, made Lebanon feel like home. A year and a half later, we came here, which made Athens feel like home.”

Finding home

Physical upheaval has been a defining characteristic of the Palestinian experience.

For many Palestinians, the search for safety and belonging continues today, as demonstrated by the ongoing displacement and killing of Palestinians in Gaza since the start of the war in October.

At 12 years old, in 1977, Watfa arrived in London with her family.

“I didn’t speak a word of English. It literally felt like landing on a different planet. The weather, the coldness of the people - it was very difficult at first.”

She recalls one formative incident in a British supermarket that helped paint her later worldview.

“The lady at the till was serving a hijabi woman in front of me and she was talking to her in the most disgusting manner. Something inside me exploded. I was only 15, but I demanded to see the manager.

“It was very instinctive. It’s the underdog. I identified with the woman in front of me despite being Christian. We have no distinction between Christians and Muslims in Palestine.”

In the end, the woman at the till didn’t summon a manager but the early encounter set the tone for Watfa’s position in British society.

As a young woman, she went on to study for a City and Guilds of London Art School, graduating in 1987.

Facing language barriers as a youngster helped develop her interest in, and pursuit of art. Creative outlets let her make sense of her trauma.

“Necessity is the mother of invention. I feel compelled to draw, that’s the extent of it,” she says.

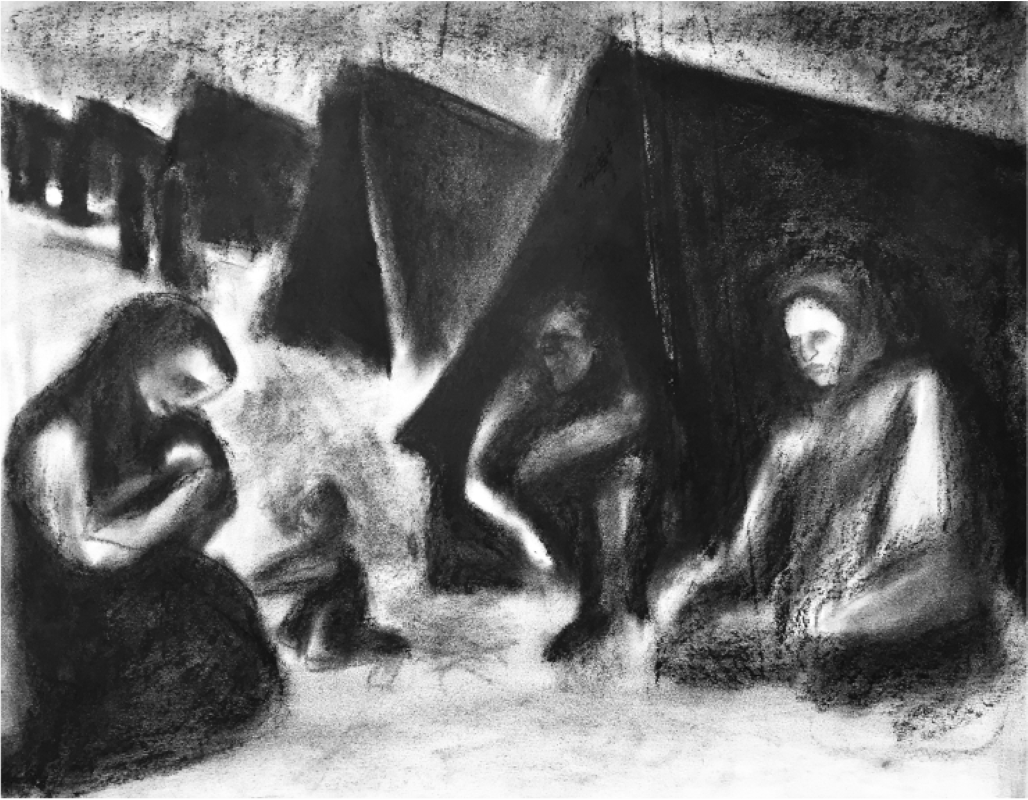

Much of her work centres Palestine, through emotive, charcoal figures symbolising the continued pain and plight of her people.

One example is Refugees, an ink-on-paper piece sketched in 1990, showing “a fragile family unit braving the unknown” as they head towards a black abyss.

The use of shadow lines in her work conveys a sense of movement while emphasising a darkness that embodies the uncertainty of the migrant experience.

On her affinity for charcoal, Watfa says: “I find it very satisfying to have my hands totally coated, as healing as having soil embedded beneath one’s fingernails during gardening.

“I love the contrast between the sharpness of white and the depth of the blackness. The colour is not there to distract. It symbolises the directness of the struggle.”

Watfa also identifies a further symbolism in the contrasts of her monotone works.

“There is no parity between colonised and coloniser, indigenous and invader. The more they try to erase us, the more light they shed on their darkness.

“But perhaps the most pertinent aspect is that, as Aime Cesaire puts it: ‘No people, no country can be held hostage indefinitely. It eventually explodes. The revolt of the colonised is inevitable’.”

Art and resistance

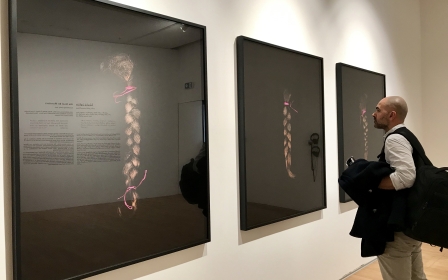

Watfa uses her art as a form of resistance, to educate and raise awareness. Her book NAKBA: Palestinian’s Ongoing Dispossession, which was published in May 2023, compiles 50 drawings, paintings, and poems from her collection.

It features Nakba, an oil on canvas piece from 1986 on the cover, with sorry faces looking longingly in all directions.

The figures gradually get smaller in size, showing an infinite queue of the Palestinian diaspora in the distance, surrounded by the heated hues of an unidentified, barren land.

'The future seems forever impalpable. Scattered to all corners of the globe, we have nevertheless refused to disappear'

- Sandra Watfa, artist

“The first woman is resigned, not out of defeat but from a resolute choice to resist through survival,” explains Watfa. “She’s looking at the ground before her, lips determined, gait unwavering, committing all that was before to memory.

"For me, women have, are, and always will remain at the forefront of resistance.”

Watfa traces the roots of this dispossession to the late 19th century migration of European Jews to Palestine, as part of the embryonic Zionist movement.

Since then, the artist explains that the Palestinian people have slowly been wrested away from their native land, a process that continues to this day.

Palestinians she says are “people made destitute, dispossessed and dehumanised to this very day - every family has, or knows someone who has been martyred for no reason other than being Palestinian. It is unsurpassed racism.”

“The future seems forever impalpable. Scattered to all corners of the globe, we have nevertheless refused to disappear. Our love of the homeland means that though on foreign soil, we carry Palestine within, and much like seeds, plant its essence wherever we are.” She adds.

Watfa believes creative modes of expression hold the key to changing attitudes toward the Palestinian story.

“Art grabs the viewer through a different channel. It’s not the frontal cortex doing the analysis, it’s the heart. It circumnavigates the intellect and touches on raw emotion, so it has the power to transcend preconceived ideas.”

Her most recent drawing, The Smallest Corpses are the Heaviest, does just that. A Mother’s Day tribute protesting the killing of thousands of Palestinian children by Israel since October, it depicts a mother caressing her dead baby, who is wrapped in a white sheet.

The mother’s eyes are closed, her face buried into the nook of her infant’s neck. The embrace is warm and loving, yet filled with the devastating grief of a final “goodbye”.

Genocide

“There are no words to describe Palestinian heartache,” says Watfa. “Seventy six years and counting, it grows exponentially. The recent figures of butchered children are breathtaking, and that’s without counting those who are decomposing beneath the rubble.

'It behoves us, who don’t have bombs and bullets tearing through our babies’ limbs to speak up and do everything in our power to expose this and bring it to an end'

- Sandra Watfa

“We have attempted to struggle for our freedom through peaceful means, as in the case of the Great March of Return in 2018. The result…267 Palestinians slaughtered, like fish in a barrel, hundreds maimed and thousands injured. The ante has now been upped to a full-blown, live-streamed genocide, armed and cheered on by Western powers.”

Watfa crafted a moment from this event in charcoal at the time, inspired by a photo of a young woman up against a fence, clutching at the barbed wire that entrapped her.

“She hollers with an eternal demand for liberation. Her anguish is raw but well-seasoned with yearning. The surroundings are rough, her situation untenable, yet she stands very tall.” Watfa says.

Typically, however, her pieces are less dependent on ongoing events.

“I tend to keep it organic. As I draw, I embody the same principle as when I used to teach yoga, that of a conduit.” She explains. “The end result is always unexpected for me, and the work is never finished. It’s simply yet another stepping stone in planting a seed of empathy in others.”

Besides her art, Watfa is a committed activist. In 2014, she partnered with Inminds, participating in two demonstrations a month for seven years demanding the release of Palestinians in Israeli jails.

She motions to a piece of stitchwork on the wall behind her - a hand-stitched map of Palestine by the wife of a prisoner in the occupied West Bank.

These activities have drawn the attention of Israel’s supporters and have resulted in hostility but she explains that Palestinians within the occupied territories are still the prime victims of Israeli aggression.

“I’ve been spat at. I’ve been called a terrorist a million times. We deal with bullies in the diaspora. The people in the homeland deal with bombs and bullets. This is the difference. And it’s a huge difference.

“We’ve been seeing things we cannot unsee, as Gazans live the unlivable. It behoves us, who don’t have bombs and bullets tearing through our babies’ limbs to speak up and do everything in our power to expose this and bring it to an end. And an end will come, however long it takes.”

She delivers her words sitting in the birthplace of the Zionist dream, where Lord Balfour declared Britain’s intent to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine; an irony not lost on her and one that fuels her determination to return home.

“I’m in the belly of the beast. I’m in the country that authored our dispossession. And that is partly why I feel so driven.

“I’ve been (here) forty four years. I could be here a hundred years. It will never be home.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.