Studio Baghdad: A window into a Palestinian Jerusalem fighting against invisibility

On Monday mornings in 2014, the sun would rise over the yellow-tinted canopy of Jerusalem, recalling the “Jerusalem of Gold” of the famous Hebrew song, and I would get up with it. By six in the morning, I would either be at the Damascus Gate amphitheatre in the Old City or at a cafe in the western half named Kadoush, Hebrew for “sacred”.

I was a student of photography at Israel’s most prestigious art school, Bezalel Academy, and at either location I would meet my tutor, the photographer Yaakov Israel, along with my classmates and colleagues. Together, we would read an extract from the Hebrew translation of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, a collection of stories by the Italian author, in which a fictionalised Marco Polo tells Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan about the places he has encountered on his journeys.

After the meeting, we would each go our own way and use the lenses on our cameras to tell the stories of a city that refuses to be invisible. At the time, I wasn’t even 20, but I took Calvino’s imagination seriously, and the ideas of space and place were something I had come across at Bezalel with my teacher Miki Krastman. Those influences had impressed on me the intricate relationship between the human experience and the urban environment.

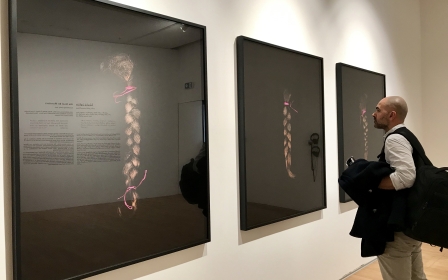

I settled on an idea where I would create a new chapter of the book, one set in an Arab city, in which passers-by go through a photography studio and take images of themselves. What would be contained within the image would be the subject themselves, the figures and scenes in the background, and their imagined memory of the city. That was Studio Baghdad - my way of capturing and preserving Arab Jerusalem, or Al Quds.

In many Arab cities before the digital age, like cities across the world, people were accustomed to visiting photography studios to mark special occasions and milestones. These places served a dual purpose, not just as a way of preserving memories but also becoming de facto visual archives.

Famous studios in the Arab world included the Shehrazade studio owned by Hashem Al-Madani in Lebanon’s Saida and the Bella studio in the heart of Cairo in Egypt. Piles of photographs and negatives in these studios gave insight into the spirit of a particular era. From the clothes of those photographed, an observer decades down the line could determine a subject’s socio-economic position, financial position and religiosity.

In Jerusalem, the Garo Studio on Salah al-Din Street still stands and is owned by Garo Nalbandian, the famous photographer of Armenian origin, who has helped chronicle the history of the holy city in his collections.

Unlike Nalbandian, my studio had a very specific purpose, and one that was a response to the existential threat the Jerusalem of the Arab collective memory was facing. The Arab Jerusalem of 2014, as it is today, is subject to constant threats from the Israeli occupation authorities and the settler movement, who are confiscating land and property, deporting Palestinian natives of the city, and slowly choking it off through urban planning from the rest of the occupied Palestinian territories.

I therefore wanted to document the city in a way that could never be erased. By choosing the name “Baghdad”, I wanted to defy the imposed barriers and borders between the holy city and the Iraqi capital, and by extension every Arab city whose glory has been seized by tyrants. But conscious of the tenuous hold the city’s Palestinian residents have on their homes, I wanted to immortalise our claim to the place.

In her seminal work On Photography, the American intellectual Susan Sontag wrote about how the image represented man’s way of asserting control over his world and granting himself ownership of it. She wrote: “A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened. The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what's in the picture.”

As part of the project, I chose five locations within Jerusalem that were emblematic of the changes being forced upon its Palestinian residents. They included places where properties had been confiscated, families were evicted and where, in some cases, the signs of demolition were publicly and painfully still visible.

I decided to set up the temporary studio booth in the style of a classic old-fashioned street studio, keeping equipment and techniques simple where I could, but also using more advanced modern photography tools, such as the DSLR camera.

What this meant in practice was a chair where the subject sat facing the camera, on the street. Simple, perhaps, but imbued with deep symbolism for Jerusalem’s indigenous Palestinian population. This is a city in danger of having its Arab past erased, along with its people. Capturing images of its streets with its people at the foreground archives a specific moment and protects a memory that cannot be wiped out.

These pictures may be distorted, their subjects may vanish and disappear, and the features of the places where they were taken may also change; but there is always a recognition, an acknowledgment, that something existed and was present, and it resembles what the picture portrays.

Before the project began, I put a call out on social media outlets with the times and locations of where the studio would be. I wanted as many people as possible to take part.

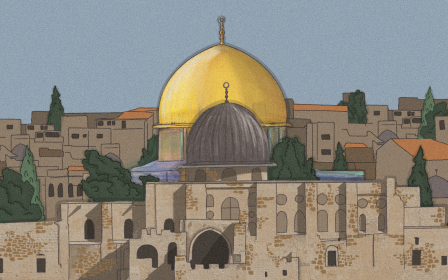

The first shoot was at Bab al-Nazer, also known as Bab al-Majlis or the Council Gate, which is one of the entrances into Al-Aqsa Mosque. The mosque is the holiest site for Palestinian Muslims and one of the most targeted by Israeli forces and settlers alike. Israeli occupation authorities routinely prevent the entry of heavy photography equipment into the site and Bab al-Majlis was therefore the closest I could get to the mosque.

I borrowed a chair from a neighbour and began inviting passers-by to sit down in front of the camera, holding the remote to the shutter, so that they could take the picture at a moment when they felt ready.

On another day and at the second location, I set up my equipment on a pavement near Bab al-Sahira, one of the main gates into the Old City. This allowed me to use the old “Post Office building” as a backdrop. Constructed during Jordanian rule between the Nakba of 1948 and Naksa of 1967, the building is now home to the Israeli occupation police and the Israeli Postal Authority. Like many buildings in Jerusalem, it had become a symbol for the confiscation of Palestinian property, as well as the gentrification and Judaisation of their neighbourhood.

Through the gates and into the alleys of the Old City was my third location, Al-Khawajat Market, which was previously famed for its cloth shops and tailors who were famous for weaving the finest traditional clothes and robes. That was in 2014. Today, many of these shops are closed, as a result of taxes imposed by the Israelis, which vendors say they cannot afford. Many Palestinian traders have long argued that opening a business in Jerusalem is more of a burden than a commercial opportunity.

The fourth location was the top of “Alladin Alley”, a key junction within the Old City, off Al-Wad Road, itself a street famous for its speciality Jerusalem cakes and falafel stands.

Fifth and finally, there was Damascus Gate, or Bab al-Amoud, a location distinct from the others for its sanctity and cinematic aura, a place unlike anywhere else in Jerusalem, like the gates of an ancient palace.

While working on the project with some photographer friends from the city, we came across two young men carrying a large sofa into the Old City. Not wanting to miss an opportunity for an unusually juxtaposed image, we asked them to stop so we could photograph them. Within seconds, 10 young men were on the sofa, placed in front of Damascus Gate, an icon of the Old City. The resulting image struck like a manifesto nailed to its walls, a declaration that Damascus Gate is ours.

A decade after Studio Baghdad, the children in the pictures have grown up and become the young men who furnish Al-Quds with its Arab and Palestinian features. Many elders featured, including Hajj Abu Radi, have left this world. He, like several others, was part of the Al-Murabitoun - Muslim faithful who maintain continuous worship at Al-Aqsa, resisting attempts by the Israeli police to force them to leave. Others remain, preserving the identity and history of the place. People like ‘Am (Uncle) Abu Adam, who I photographed at Bab al-Majlis, and ‘Am Abu Ahmed, the owner of the cloth shop in Al-Khawajat market.

Since 2014, the occupation authorities and settlers have become more aggressive in stamping out the Palestinian presence in Jerusalem. Raising the Palestinian flag is illegal in Jerusalem and waving it even in private is a punishable act.

Today it is no longer possible to place my studio chair at Alladin Alley, as the spot has turned into a checkpoint manned by armed occupation forces. Its purpose is to restrict the flow of worshippers into Al-Aqsa, the third holiest site in Islam, by demanding identification from the faithful and only allowing entry to those approved by the Israeli occupation authorities. The situation is the same at every entry point into the mosque.

Even the Damascus Gate is no longer the same; the memories of that period will remain just that, and it will be difficult to create new ones, given the strangulation of the area in the decade since. The events of 2015 were a turning point, known as the Al-Aqsa uprising; they involved active protests at the site against the constant storming of the site by settlers and the Israeli occupation forces.

Today, three military observation towers, barracks and surveillance installations, all guarded by heavily armed troops, work to remind Palestinians of Israeli hegemony in this once sacred spot. Palestinian youth are routinely humiliated and fines are imposed on those who sit around the area or dare set up stalls to hawk goods, once traditional characteristics of the place and its charm.

There is even a memorial for two Israeli soldiers who were killed in confrontations with Palestinians. Once, Jerusalemites would gather around this historic landmark and share a cup of tea or coffee, treating it like the traditional “Downtown” areas of Arab cities, but that is no longer possible. Anyone who tries to inject that old life back into the area must avoid the eye of vigilante police officers on the lookout for anyone trying to revive its old atmosphere. The policy means that there is constant confrontation between the occupation forces and Palestinians, which has sometimes led to the killing of Arab youths.

These policies come amid an increase in settlers storming Al-Aqsa, which involves shutting down the compound to Muslims and allowing large numbers of ultra-nationalist Jews into the area. Their end goal is the destruction of the seventh-century mosque and its replacement with the third Jewish temple.

The settlers come with armed escorts from the Israeli occupation forces and arrange their storming attempts in collusion with officials, who are often open about their support for their endeavours. Each transgression brings clashes between Palestinian worshippers, trying to secure their basic rights to worship at their sacred site, and Israeli forces. The Palestinians' fear, which they have good cause to hold, is that the Israeli state, under the influence of hardline Jewish religious groups, is planning to partition the mosque in favour of the settlers.

Al-Khawajat Market, like every alley, street and house in Jerusalem, has not been spared from this policy of Judaisation and displacement. This erasure comes coupled with direct, ethnically based expulsion of Palestinian residents from their homes in occupied East Jerusalem.

Scenes of Palestinians being expelled from their homes and escorted out by Israeli police only to be replaced by settlers are familiar in the area surrounding Al-Khawajat. Recently, the Sub Laban family were expelled from their home overlooking Al-Aqsa by occupation forces. All of this is happening in order to establish a Jewish majority and dominance in the city of Al Quds, so that the percentage of Palestinians does not exceed that of Israeli Jews in the city.

Today, the occupation continues to produce new laws against Palestinians, laws that often deprive us of our birth right to sit at the Damascus Gate, pray in the third holiest sites for Muslims, and perform the rituals therein.

Since 7 October and under the cover of the war, the District Planning and Construction Committee has approved more than 9,000 housing units for settlers in new and existing settlements in the city of Jerusalem. Such rapid regulatory procedures usually take years to complete, but have been hurried through by the godfather of settlement, the current Minister of Finance Bezalel Smotrich.

The occupation wants us to wake up one day from our sleep, to a reality where we do not have Al-Aqsa near us. Where we cannot find men named Abu Shukri or Bin Izhiman, or markets named Al-Attarin or Al-Khawajat. It is an attempt to separate we Palestinians, our history, our religious sites and our cultural heritage from our land, so that we become uprooted individuals without any connection to the places we originate from.

The Israeli army is doing this in Gaza, as part of the same systemic process, destroying its monuments, landmarks, and the land itself so that there remains no physical connection left between a Palestinian and the place they were born - as if it had never existed in the first place.

Israel’s occupation wants the Arab-Palestinian Jerusalem to disappear, never to be seen again, as it continues its policy of Judaisation, settlement, demolition, confiscation and importation. If it gets its way, we will be left with an imaginary city that does not exist, just as Italo Calvino searched for cities other than the cities of Monsa and the ruins of Kublai Khan.

But while Israel tries to make reality the Jerusalem of its imagination, we fight to keep our historic Jerusalem alive. Rome burnt under Nero, but it was rebuilt, and we Palestinians will build even as the city of our imaginations is burned.

It is therefore necessary for us to confront these attempts to erase us, whether it is through the medium of photography, video or other forms of media. By documenting the present, we challenge this erasure and challenge time, while restating our right over these spaces.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.