Who was Moses Maimonides? The great Jewish philosopher of the Middle Ages

Within a white mausoleum in the city of Tiberias, in what is now Israel, lies the grave of the most renowned Jewish thinker of the Middle Ages, Moses Maimonides.

Born in 1138 in the Spanish city of Cordoba, the philosopher and theologian came from a long line of rabbis and was destined to follow in their footsteps.

At the time of his birth, Andalusia, the name given to Muslim-ruled areas of Spain, was ruled by the Almoravid empire; but early in Maimonides' life the area was taken over by the Almohads, a group of North African Berbers who initially implemented hostile policies against Christian and Jewish subjects.

Isaac Newton’s thoughts on the history of religion were influenced by Maimonides' Mishneh Torah

At 10, Maimonides fled Spain with his family, fleeing initially to Fez in Morocco before settling in Fustat in Egypt in 1166, where he would spend the rest of his life, until his death in 1204.

Commonly known by the Hebrew acronym “Rambam” (for Rabbi Moshe Ben Maimon), Maimonides was a prolific writer of rabbinic, philosophical and medical works.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

His works present a rationalist view of Judaism as a way of life grounded in perfecting the human intellect through religious commandments, and are a source of inspiration and fascination for Jewish and non-Jewish readers alike.

In Fustat, roughly corresponding to modern Cairo, Maimonides worked as chief judge of Jewish courts, but since he hated taking money for work on the Torah, he supplemented his income with a thriving medical practice.

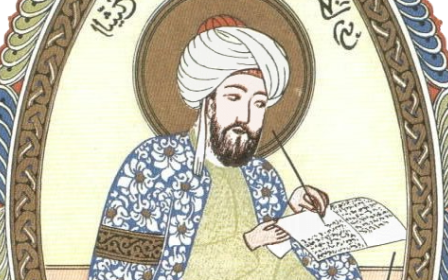

Eventually he became popular with Muslim noblemen and even became one of Salahuddin Ayyubi’s court physicians.

Despite his busy schedule, Maimonides had time to write around 20 works on Jewish scholarship, medicine, astronomy and philosophy.

Notable works

Maimonides began writing on astronomy as a young man. One of his most important works in the field was about the Jewish calendar, titled Laws of the Sanctification of the New Moon. The philosopher also wrote several medical treatises that were commissioned by Muslim nobles, such as Regimen of Health and On Asthma.

His main contributions, however, were in rabbinical studies and philosophy, among them three enduring rabbinical works in which he systematised Jewish laws and beliefs.

The first major work was the Book of Commandments, in which Maimonides codified the 613 scriptural commandments found in the Hebrew Bible, or the Tanakh, and a work entitled Commentary on the Mishnah.

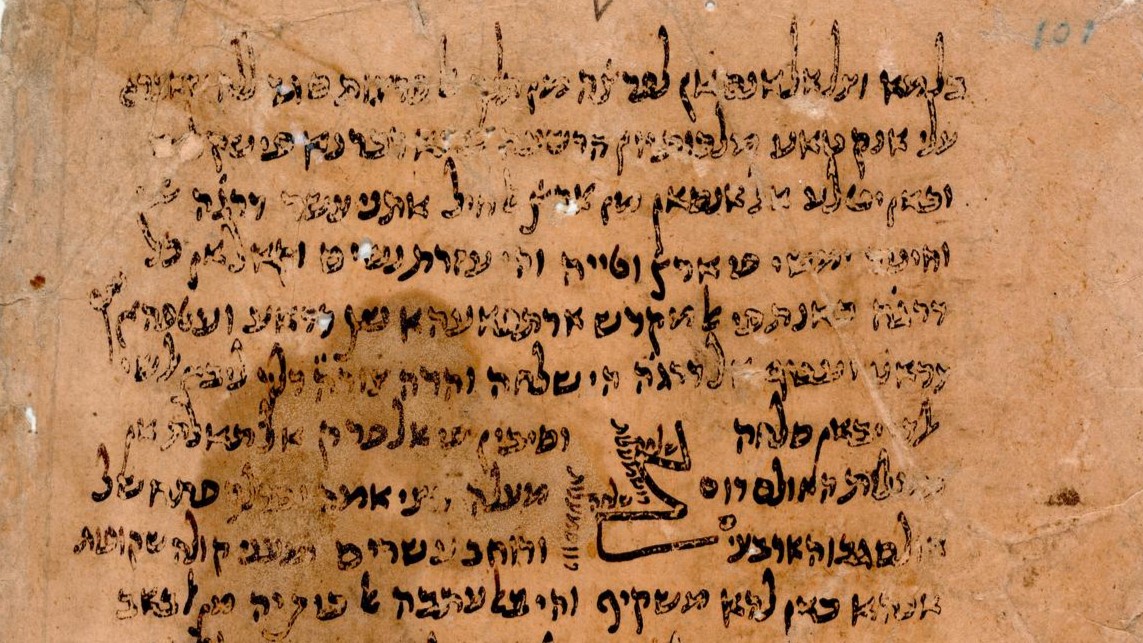

His most ambitious project was the Mishneh Torah, a 14-volume compendium on Jewish law, composed over 10 years.

One of the most important literary achievements of the Jewish Middle Ages, the Mishneh Torah contains detailed information about the Talmud, Jewish rulings (halakhot) and interpretations of the Torah, organised in an accessible and transparent manner.

Meant as a guide for practical observance and a reference for a layperson, the Mishneh Torah was the most comprehensive and innovative post-Talmudic work written at its time. Indeed, the 13 articles of faith that Maimonides laid out within his rabbinical works continue to be widely known in the Jewish faith.

At 47, Maimonides also began work on his celebrated philosophical treatise, Guide for the Perplexed, which addressed common questions about the nature of religion. It dealt with a vast array of religious and philosophical issues, including the nature of God, prophecy, providence and cosmology.

He is critical of efforts by Muslim theologians to reduce the entirety of the natural order to a sort of miracle of God’s will

In the Guide, a puzzled believer could find out how one could reconcile scientific discoveries with descriptions of events described in the Torah - understanding the scripture rationally.

Originally written in Arabic, an introduction reads:

“The object of this work is to enlighten a religious man who has been trained to believe in the truth of holy Law, who conscientiously fulfils his moral and religious duties, and at the same time has been successful in his philosophical studies.

Human reason has attracted him to abide within its sphere; and he finds it difficult to accept as correct the teaching based on the literal interpretation of the Law…Hence he is lost in perplexity and anxiety.”

His philosophy reveals a strong understanding of an array of thinkers, such as Al-Farabi, Aristotle and prominent contemporary Muslim theologians.

The interpretation of Maimonides’ works is a source of much debate and enigma. He suggests in Guide for the Perplexed that he has hidden meanings in his works, to prevent from disclosing esoteric secrets to those who are not ready for them. This has had the effect of encouraging numerous interpretations of his works in an attempt to understand what he truly meant.

Philosophy

Maimonides combined traditional Jewish teachings with philosophy and attempted to give religious doctrine a rational foundation.

The Torah, according to Maimonides, serves man’s two perfections: the perfection of the human body and the perfection of the human soul. It helps perfect the human body by creating laws to ensure a society free of violence and by engendering ethical qualities that promote peaceful interpersonal relationships. The scripture also perfects the human soul by giving mankind correct views about God; through knowledge, man can attain the highest human happiness of knowing God.

Maimonides’ conception of the purpose of life is the spiritual delight that comes from knowing God. For this reason, he tried to show how the commandments are a means to the end of knowing God and avoiding idolatry.

Philosophising and knowledge of the natural order leads a religious individual to awe and love of God. Because of this, in the Mishneh Torah Maimonides spent time explaining the scientific structure of the universe.

An extract from the Laws Concerning the Foundations of the Torah reads:

“I shall explain some large, general aspects of the Works of the Sovereign of the Universe, that they may serve the intelligent individual as a door to the love of God, even as our sages have remarked in connection with the theme of the love of God, ‘Observe the Universe and hence, you will know Him who spake and the world was.’”

Maimonides was committed to the view that God is not made of physical matter, is transcendent, and beyond human comprehension: we cannot speak of God directly, and instead all attributes must be negated of God. For example, one cannot say that God is powerful, but rather that God is not weak. Scriptural passages that speak of God in positive terms are merely allegorical and must be reinterpreted correctly.

The philosopher also had a unique understanding of prophecy as a natural event. A prophet is a person who, through his strong psychological powers, dreams intellectual truths in symbolic images which he then conveys to other people.

Moshe Halbertal explains in his book, Maimonides: Life and Thought: “God does not reveal Himself to the prophet in a dream; rather, the prophet dreams that God revealed Himself to him.”

With this view of prophecy, Maimonides reinterprets prophetic visions in the Torah not as external events, but events within the prophets’ consciousnesses. This naturalisation of prophecy became a source of controversy among other Jewish thinkers.

Is the universe eternal?

One of the central problems occupying Guide for the Perplexed is whether God created the universe ex nihilo - out of nothing - or whether it has existed for all of eternity. The former is a traditional theistic belief and suggests that God has a will: at some point, He willed that the universe come into existence.

According to the proponents of the pre-existence of the universe, the issue with divine will is that it implies that God changed his mind at some time in order to will the universe into existence. God, they argue, must be timeless and has always done what he intended to do. Since He cannot change, the universe must have always existed.

The implications of this question are heavy: all Abrahamic religions conceptualise God as vested with personality and will so that He can provide commands, judgment, reward and punishment. But does this suggest that He is imperfect?

Maimonides was absorbed by this problem across 37 chapters in the guide. After all, a perplexed person of faith would encounter arguments for the eternality of the universe - at that time considered the cutting edge of science - and think that the God of the Torah who wills the creation of the universe is false.

Eventually, he shows that the eternality of the universe is not scientifically established, and that in fact a newly created universe is more probable. His reasoning for this is interesting: medieval astronomy is unable to elegantly explain the messiness of planetary and celestial motions. The arbitrariness of scientific explanations is evidence that God must have chosen to create the Universe.

He writes:

“There is a phenomenon in the spheres [the universe] which more clearly shows the existence of voluntary determination; it cannot be explained otherwise than by assuming that some being designed it: this phenomenon is the existence of the stars…What determined that the one small part should have 10 stars, and the other portion should be without any star? And the whole body of the sphere being uniform throughout, why should a particular star occupy the one place and not another?

The answer to these and similar questions is very difficult, and almost impossible, if we assume that all emanates from God as the necessary result of certain permanent laws, as Aristotle holds…But if we assume that all this is the result of design, there is nothing strange or improbable: and the only question to be asked is this: What is the cause of this design?

The answer to this question is that all this has been made for a certain purpose, though we do not know it; there is nothing that is done in vain, or by chance.”

Maimonides did not think that the universe having a beginning must mean that it would have an end. The universe could go on for all of eternity once it was created:

“It is not contrary to the tenets of our religion to assume that the Universe will continue to exist for ever…According to our theory, taught in Scripture, the existence or non-existence of things depends solely on the will of God and not on fixed laws, and, therefore, it does not follow that God must destroy the Universe after having created it from nothing. It depends on His will…”

Despite thinking that God created the universe, Maimonides is critical of efforts by mutakallimun (Muslim theologians) to reduce the entirety of the natural order to a sort of miracle of God’s will. God created a natural order that must be admired and become a source of awe and wonder that eventually drives religious feeling.

Legacy

Maimonides’ rabbinical works and philosophical texts were both praised and controversial.

The Mishneh Torah became the most discussed Jewish work since the Talmudic period and also influenced Christian Europe, through Latin translations from the 16th to the 18th century. Even Isaac Newton’s thoughts on the history of religion were influenced by the Mishneh Torah.

Like the Mishneh Torah, the Guide for the Perplexed is studied to this day. Virtually every Jewish medieval thinker was influenced by it, including Gersonides and Moses Narboni. Over a dozen medieval Christian philosophers cite or borrow from the guide, including Thomas Aquinas when discussing the creation of the world.

Maimonides’ views did not go uncensored. Some criticised him for reinterpreting scriptural accounts of prophetic experiences as visions and not literal events, and for giving pragmatic justifications for Jewish commandments.

The Mishneh Torah and Guide for the Perplexed were banned in France in the early 13th century, when Jewish opponents of Maimonides complained to church authorities.

Maimonides’ works led to two transformations in the Jewish medieval world. First, he systematised complex Jewish texts and beliefs through his rabbinical works in an unprecedented way.

Second, he sought to change the religious consciousness of the Jewish people, to urge them against anthropomorphism of all kinds, including what he saw as idolatrous interpretations of the Torah. This rationalist turn gave a philosophical foundation to the Torah.

Maimonides’ works continue to be a fruitful source of enticement, mystification and insight. It is often said in praise of Moses Maimonides, “From Moses to Moses, none arose like Moses.” In light of the lasting allure of his works for readers across all religions, this saying has proven to be true.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.