Masameer: How a zany YouTube cartoon captured the pulse of a changing Saudi Arabia

In the fictional Saudi Arabian governorate of Masameer, knowledge is the most dangerous of commodities: knowledge of the reality hidden behind the town’s seemingly innocuous facade; of the outside world; and of the self.

This notion is most perfectly crystallised in an episode when the owner of the town’s book store goes on a search for a missing copy of Woman and Sex, the notorious 1972 study by the late Egyptian feminist writer Nawal el-Saadawi.

Mention of the book drives the townsfolk into frenzy; their reaction ranges from apprehension to teeming curiosity.

Preceding a violent climax that ends with murder, the struggle over the secretly shared book is marked by prison time and vandalism.

It’s over the top and darkly comic, but there’s a painful truth lurking underneath the outlandish action.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Saadawi was demonised in the Arab world for decades: a poster girl for second-wave feminism, whose rise paralleled the rise of Wahhabism in the Gulf and subsequently the Arab world.

According to the New York Times, she was included on a so-called death list published in Saudi Arabia.

The plotline of this Masameer episode is exaggerated, but the fear of Saadawi’s influence and the rebellious knowledge she presented is a reality treated subtly in this otherwise colourful cartoon universe.

Satire in a new Saudi Arabia

Masameer is the Arab world’s greatest cartoon series. It has been brought into the international spotlight after its producer, Abdul Aziz al-Muzaini, revealed that a Saudi court has sentenced him to 13 years in prison, in addition to a 13-year travel ban, over accusations of promoting terrorism and homosexuality.

For fans of Masameer, the news was not surprising. The show has been the most daring, most envelope-pushing Gulf series in history, and certainly the boldest Arab cartoon.

Even given its efforts to promote itself as a major touristic and business attraction free from the stern restrictions of the past, Saudi Arabia remains a country in transition: a nation boasting some of the most exciting talents in the region and a society that ranks among the most liberal in the Gulf.

It is, nonetheless, still ruled by the same iron fist responsible for the killings and prosecution of journalists and activists.

The Masameer case was exceptionally stark, however, and very telling of how erratic and volatile the kingdom is when it comes to creative arts and criticism.

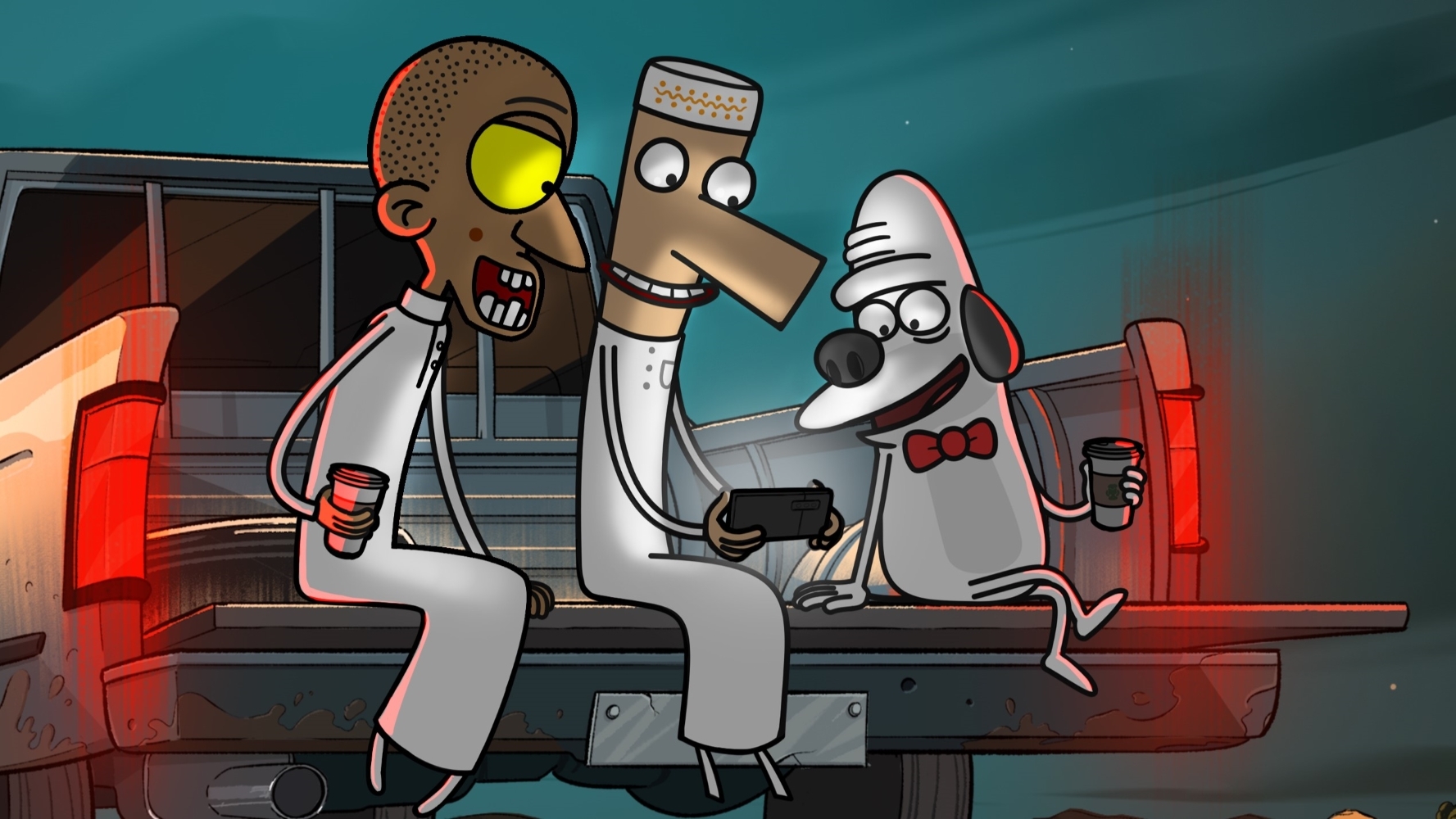

The very first episode of Masameer, titled Gaalony Koraagian (They Made Me a Local Football Fan), landed on YouTube in 2011 and was unlike anything presented in Arab animation before.

The animation was simple but not elementary, frantic in its pacing but with precisely composed frames that amplify the comedy.

The interchange of fusha (classical Arabic) with colloquial Saudi dialogue was a stroke of genius, responsible for shaping and rebranding Saudi humour, a brand of comedy deemed strictly local by past live-action sitcoms.

Most notably, the tone of the series was satirical from the outset: acerbic, and wry.

Raising the stakes

From the start, Masameer established itself as the most sophisticated animation in the Arab world. Even Egypt, with the oldest and largest entertainment industry in the region, never managed to produce an animated work to rival the Saudi upstart.

The show emerged at a time of a buzzing cultural renaissance arising from the 2005 King Abdullah Scholarship Program (Kasp); a government-sponsored initiative created by the former ruler, which sent thousands of Saudi millennials, both male and female, to study in the US, UK, Australia and Canada.

In the 2014 and 2015 academic year alone, 200,000 Saudi students were studying abroad.

In Masameer, Saudi Arabia is

a characterless place populated by idiotic, self-centred buffoons unaware of their immense privileges

The opening of Saudi society was definitely not the brainchild of incumbent Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), as it is commonly believed: the liberation of the Saudi society was years in the making. MBS simply rode the wave and claimed the project as his own.

Masameer was a by-product of this new, thriving cultural movement, which sought to work around censorship to tackle a Saudi reality that has long been safeguarded from censure.

Three men have been responsible for Masameer from its inception: writer Faisal Alamer; Malik Nejer, the director; and executive producer Abdul Aziz al-Muzaini.

Masameer quickly became a cult hit in the kingdom, with its biting satire reflecting the country’s contemporary concerns in a brazen fashion unmatched by any rival.

The Saudi Arabia of Masameer is a regressive, aggressively materialistic, American-influenced province torn between a laughably archaic past and cynical present; a characterless place populated by idiotic, self-centred buffoons unaware of their immense privileges.

Countless topics were tackled in the early days of the show, on YouTube: from suffocating consumerism and macho culture to the pressures of orthodox family and institutional corruption.

Incompetence, absence of individual freedoms and infantile pop culture are some of the recurrent themes tackled so perceptively in dizzyingly eclectic form, reminiscent of the likes of Rick and Morty and SpongeBob SquarePants, albeit with a distinctly Saudi flavour.

Masameer’s creators have never shied away from criticism, and the more popular the series became, the higher the trio raised the stakes.

There have been a number of highlights in its YouTube incarnation, but one that stands out is Genood Al Khorafa (Soldiers of the Fantasy), from 2015, in which the three main characters start a project they hope will make them bourgeois, only to find themselves targeted by the Islamic State group (IS).

Soldiers of the Fantasy also took aim at Islamic fundamentalism and religiosity in general. Its sentiment may or may not have put the creators in hot water with the country’s still powerful religious authorities.

Netflix deal

Having garnered millions of views along the years and securing numerous sponsors for succeeding episodes, it was only natural for Netflix to come calling when it began to enter the Saudi market in the second half of the past decade.

In 2020, the American streaming giant signed a five-year deal with Masameer’s parent studio, Myrkott, to expand the global reach of the country’s premier online series.

The first fruit of the new Netflix deal was Masameer: The Movie, an ill-fated 2020 cinematic adaptation too reliant on American formulas and devoid of the nimbleness and cunning undertones that made the series a regional phenomenon.

With the newly rebooted series, Masameer County, the following year, Myrkott used the unbridled freedom Netflix granted to take its humble creation to new, adventurous heights.

The raunchy humour, sex, political commentary and gay subtext were multiplied, resulting in some of the most deliciously outrageous Arab TV to emerge since Bassem Youssef’s Al Bernameg and the heyday of the Arab Spring.

Several episodes from the two seasons that ran from 2021-2023 pushed censorship limits to an unprecedented degree.

In Ice Cream, the infamous opener of season one, Bandar, one of the main characters, goes to extreme lengths to quench his cravings for ice cream, going as far as joining IS in his futile pursuit for excess.

According to Muzaini, the satire went over the heads of Saudi officials,who instead assumed that the creators were saying that “if you went and fought with the Islamic State and you died like Bandar in the ice cream episode, you’ll go to heaven”.

There is, however, more to this particular episode - and the Netflix spin-off in general - than this trifling accusation.

In its scathing criticism of the rich and the classism dominating Saudi society, Masameer paints an unflattering portrait of the Gulf: a place governed with an entitled, lethargic and reckless class addicted to material comforts, which treats other non-western races as disposable minions.

The Muzaini sentence has proven that the picture in the new kingdom is not as rosy as Arab creators were hoping

Plenty of gay subtext is found in the series, including inWashingtonia, which uses BDSM references in side-splitting fashion, and Pimple, where Saltooh, one of the leads, spends the duration of the episode struggling to remove a pimple that has inexplicably surfaced on his backside.

Latrine of Secrets, which is largely set in a toilet, takes a swipe at tribalism; Elevator Pitch touches upon infidelity, suicide and faux spirituality; while the aforementioned Clearance - the greatest episode of the entire series – confronts censorship head on.

Masameer is not only the funniest Arab cartoon in history, it’s the most critical series the Gulf has ever made.

Although it never touches on the royal family - the biggest and possibly the sole red line for millennial Saudi storytellers - every aspect of Saudi life has been fair game for Nejer and his crew.

Opening the flood gates of expression

Did the show overstep the limits of Saudi censorship? Was the Netflix spin-off a step too far? No one knows, because no tangible parameters have been set to begin with.

Masameer signalled a carte blanche for Saudi-affiliated creators to do whatever they wanted as long as they steered clear of MBS and his posse.

The Saudi tourism and entertainment sector has been aggressively courting the biggest talents in Arab entertainment and Hollywood, in its ambitious plan to become the hub of Arab culture and entertainment - a position held by Egypt for more than a century.

While academia and the arts sector - far less in the spotlight than film and TV - have managed to create a space for expression and a freer discourse, entertainment remains subject to the whims of the authorities.

The Muzaini sentence has proven that the picture in the new kingdom is not as rosy as Arab creators were hoping.

A few days after the release and immediate deletion of his video, Muzaini posted another video on X, describing the sentence as a “simple matter between the father and his son/brother”, insisting that he will “live and die" in Saudi Arabia.

His subsequent posts are essentially mini-love letters to MBS. Rumour has it the sentence has been overturned, although given the non-existent transparency in the kingdom, one can never know what happened exactly.

Self-censorship is now on the rise, in an industry already plagued by mounting restrictions and prohibitions

Muzaini had been the poster child of MBS’s new Saudi Arabia: a hugely talented, resourceful producer who made his name inside the kingdom and who embodied the modernity of a new culture where criticism, no matter how blatant, is allowed and encouraged.

Recent months have cast doubt over the true limits of freedom in a society that continues to be at odds with its autocratic rulers. The Muzaini case rippled across not only Saudi Arabia but the Arab world.

Most Arab filmmakers have become heavily reliant on Saudi Arabia, not just for film funds but for advertising money. In a span of a few years, the Saudi market has grown into the biggest and most lucrative in the region.

The livelihood of legions of directors, technicians and talents are now dependent on the kingdom, and it’s only natural that no one wants to upset the guys upstairs by churning out works that could be interpreted as critical of religion or governance.

Self-censorship is now on the rise, in an industry already plagued by mounting restrictions and prohibitions.

Saudi Arabia holds the keys to the progress of the Arab TV and film industry: the money and cinemas and channels that could revolutionise storytelling in the region.

But without freedom, without nurturing critical thinking, without empowering Arab artists to allow their imaginations to engage complex realities in whatever form they want, the resultant works will be as sterile and as insignificant as those that preceded the Masameer era.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.