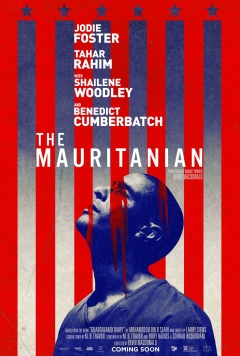

The Mauritanian: A film about surviving Guantanamo

In one scene in Kevin Macdonald’s Guantanamo drama, The Mauritanian, the lead character sits in his cold, cramped prison cell inside the infamous US prison in Cuba.

As his guards enter the room, Mohamedou Ould Slahi, the titular Mauritanian played by Tahar Rahim, bursts with joy, giving his captors high fives, as they greet him in turn with warmth.

If not informed by Rahim’s intense portrayal of Slahi’s undiminished humanity, the scene may have appeared unsettling to the viewer. Slahi was after all in jail without charge and subject to torture whilst there.

Instead Slahi, in his response to his captors, encapsulates what is at stake in a movie that spends much of its time on the legal wrangling between defence lawyer Nancy Hollander (Jodie Foster, who won a Golden Globe for her performance) and military prosecutor Stuart Couch (Benedict Cumberbatch).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

US authorities knew that Slahi had once sworn allegiance to al-Qaeda and fought against Soviet-backed Communists in Afghanistan for three weeks in the early 90s before breaking off ties with the group. Slahi has stated that he had never been an enemy combatant against the US.

Nevertheless, Washington determined that Slahi must be a "high-value" al-Qaeda operative, and viewed him as one of the group's recruiters.

After the 9/11 attacks, Slahi was arrested in his native Mauritania in 2001 and then taken to Amman, where he was held in solitary confinement for more than seven months.

The US later moved him to Bagram air base in Afghanistan and from there, he was flown to Guantanamo Bay.

At the prison, guards used a number of torture techniques on him, including sleep deprivation, stress positions and the use of sexual threats against his mother, as well as being exposed to long bouts of excruciatingly loud heavy metal music.

He was released without charge after 14 years in prison. During that period he wrote about his experiences in what would become the memoir Guantanamo Diary, a best seller, released in 2016.

Based partly on that book, Macdonald’s film joins a cabal of movies that interrupt Hollywood’s manufacturing line of films glorifying the exploits of politicians, spies and soldiers fighting the so-called War on Terror.

At its strongest, The Mauritanian speaks about how Slahi pushes through the adversity of his torture and inhumane treatment, redeemed eventually by a letter confirming his release.

In this regard the film is more than just window into court procedure or a Chomsky-esque documentation of American human rights abuses against an innocent man, but a story in which the target of those violations and their experience is the subject.

Like Mat Whitecross and Michael Winterbottom’s 2006 offering, The Road to Guantanamo, The Mauritanian fixes its lens firmly on the war’s less glamorous underbelly. It is there that the mute, muffled and masked figures paraded to their cells in orange jumpsuits, with their feet and hands chained, have their voices heard.

It was Slahi, in his role as a consultant, who helped the film's creators bring accuracy to the visuals, and his conversations with Rahim that helped bring authenticity to the performance.

Speaking to Middle East Eye, Slahi shares his experience in watching the movie develop from its conception to the silver screen.

Q: What was your reaction to the idea of a movie based on your experience at Guantanamo?

A: When the book came out, my lawyer visited me. I was in Guantanamo Bay and my lawyer was doing one of her routine visits. She told me that some producers - namely Lloyd Levin and Beatrice Levin, his wife, wanted to adapt the book into a movie. Others including Kathryn Bigelow were also interested, but my lawyers chose Lloyd Levin. I said yes. I mean, what else do you want me to say? It was amazing.

Q: How much of the film were you consulted on?

A: I was involved but I'm not an artist, and this is a piece of art. So, I didn’t interfere and say do this or do that - it's not my place. Whenever they asked me, I answered. I told them [stories] to the best of my recollection. I told them this was like that, that was like this.

I was denied entry to the US (for the film's rollout) not once but twice. I was denied a visa twice. It was very frustrating, but do you see the problem with the United States? They have a problem with the world. This is a very cold fact that we have to live with.

If you have been to Guantanamo Bay, you would expect [the US] to say: "That’s horrible. I'm so sorry (about what happened). What can we do to help you?"

Instead, they said, "Screw you. If you've been in Guantanamo Bay that means that you deserve to be in Guantanamo Bay." A circular argument.

Q: Did the film do an accurate job of portraying your time at Gitmo?

A: Yes. I always say that Guantanamo Bay itself is a dramatisation of the movie They [a 2002 horror film about night terrors]. You cannot represent what happened (in Guantanamo) on TV - seventy days without sleep. Seventy days, the first seventy days. No sleep. But the movie did a good job.

Q: Was the film's depiction of the Guantanamo Bay prison camp accurate?

A: Yeah, eerily so. I visited the sets in South Africa and it was eerily similar.

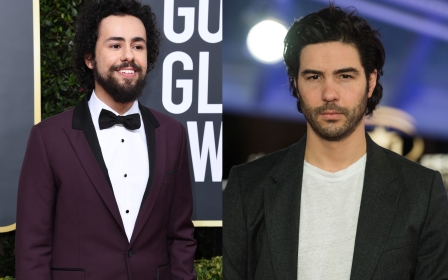

Q: How did you find Tahar Rahim's portrayal?

A: I saw his movie A Prophet. I knew that he was a very good actor and I loved that movie. And he is very good looking. I'd like to use his profile picture and trick people into thinking that's how I look.

I am not an artist, I'm not in a place to judge his performance, but my instinct tells me that he's a good actor. I don't know how I act. I don't know what I look like, I don't know how I talk.

Q: What did you feel when watching the film? Did it trigger any emotions?

A: The psychiatrists told us there is no difference between living something and remembering it. It's basically the same. So of course when watching the film I got really scared. I even began to get sweaty. And when it comes to violence I could not watch. I had to step away or... no, I just couldn’t watch that.

Q: Were there other parts of the film that were difficult to watch?

A: My book only talks about my point of view and what I saw. I was surprised that there was so much going on behind the scenes. What really surprised me was the idea that those people on the other side were essentially trying to kill me. That's not a very flattering idea, you know? And kill me for what? What did I do? You come and kill me, just like that? That was very, very distressing to watch.

Q: Was it uplifting for you to watch Stuart Couch, played by Benedict Cumberbatch, eventually remove himself from the trial because he saw its flaws?

A: Oh, it's like a sigh of relief, but it's not a complete win. A complete win means this is all fake, that they are making up stuff. But in his initial resignation, he was upset that they couldn't find evidence against me. And everybody is innocent until proven guilty. I don't know what kind of evidence he could have seen that I didn’t know of myself. That’s very puzzling to me, that people are convicted of something they didn't do.

It's tragic but America is a great country, the American people are, by and large, good people. That's my assessment, honest to myself and to Allah.

But after 9/11, President Bush said their way of life, democracy and freedom were under attack. But, right after the attack, they started to attack freedom. That’s very ironic, to be honest.

Q: Since the US launched its "war on terror", several Hollywood films have promoted a narrative that Washington was pursuing justice. What was your experience watching such films?

A: I read somewhere that a very good example of a propaganda movie was Top Gun. It is a good movie and I have watched it but it was propaganda, I found out later on.

Of course, I read that the filmmakers also worked with the Pentagon. At least that's what I read, but it did make sense. Also, a very blatant piece of propaganda is Zero Dark Thirty. They didn't bother to tell the other side of the story - about the people who died, including innocent people who died under torture. It's very ugly but the movie did not show that. The only narrative they put forward was that you can torture people and get information out of them.

Q: There were some parts to your story that were highlighted in the film, such as the friendship you developed with your prison guard, Steve Woods. Were there other parts of your story that you wished had made it onto the screen?

A: Yeah, I think the Canadian angle, I wish they portrayed that. Because it showed the shameful role that Canada played in my rendition and torture. Even though I was a legal immigrant in Canada and I deserved to be protected by Canadians. Instead, they completely swallowed everything that the United States government fed them.

Wrong intelligence, and we know it is intelligence that was wrong. Even American intelligence knew that I was not part of the 9/11 plot. The American government knew that I'm not part of the Millennium plot [the Americans alleged Slahi was involved in a plot to bomb Los Angeles international airport], by their own admission. But Canada bought into this fantasy. And they completely threw me under the bus.

And also Jordan because I want that country to stop hurting their own people. You can bitch about America all you want. But what about our regimes? What kind of regimes turn over their own citizens? What kinds of regime tortures detainees from their own countries?

Q: What is the main takeaway you want audiences watching this film to leave with?

A: Democracy works. The rule of law works. Dictatorships do not work. Torture does not work.

Parts of this interview were edited for clarity and brevity

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.