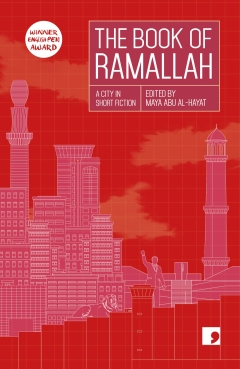

'The Book of Ramallah': Ten stories that paint a portrait of a city

The Book of Ramallah collects ten short stories by ten Palestinian authors, who range from emerging to globally acclaimed, and their overlapping portraits show a mirage of an independent Palestinian city, surrounded by checkpoints that are all too real. It’s a place where the characters’ sanity and autonomy are always under threat, where their stories are constantly in question.

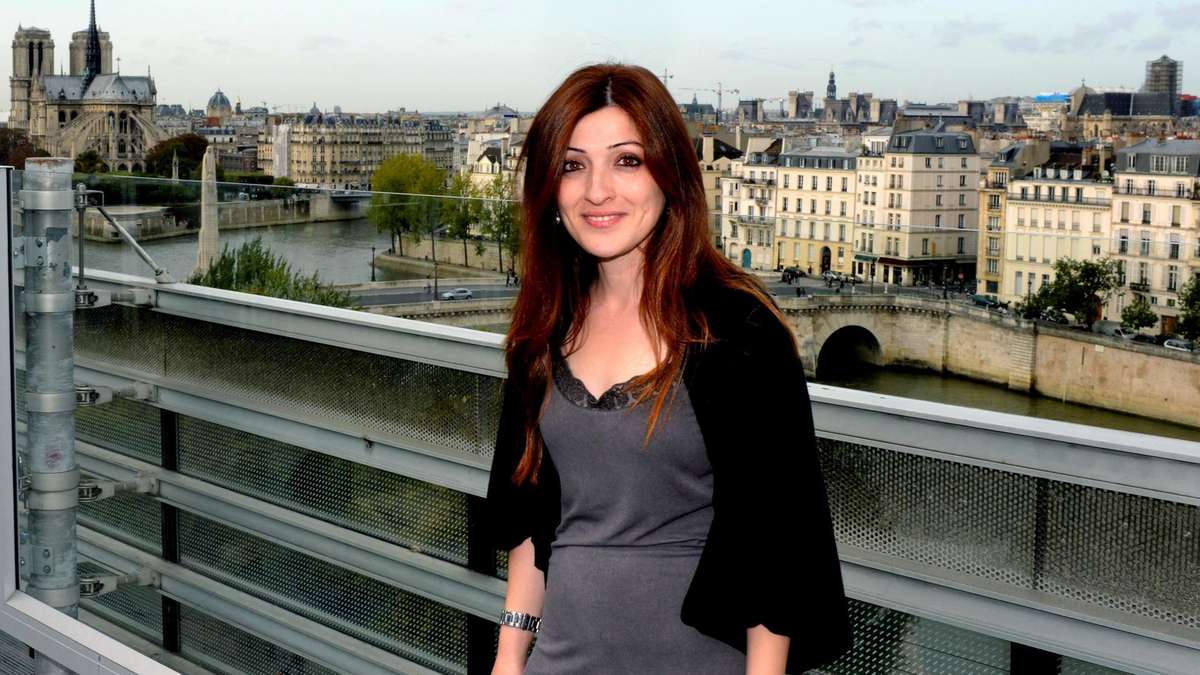

Like the other books in Comma Press’s Reading the City series, The Book of Ramallah, edited by Jerusalem-based Palestinian writer Maya Abu al-Hayat, brings together authors from different backgrounds and generations, whose fictions are crafted in diverse styles, from romantic realism to satire to the surreal.

This isn’t a portrait of one, singular Ramallah. But taken altogether, these Ramallahs are far quieter than the city stories in the Book of Cairo and Book of Khartoum, and they are less suffocating and more sarcastic than the stories in the Book of Gaza.

Yet, in their quiet way, the characters in this collection struggle for control over their lives and the world around them. They fight against social conventions, the vagaries of memory, and the restrictions of Covid-19. But most of all, they fight for autonomy within the Israeli occupation.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The collection opens with an introduction that gives us a short history of the city. Unlike nearby Jerusalem or Bethlehem, Ramallah doesn’t have an iconic history. Editor Maya Abu al-Hayat writes that, for a long time, Ramallah was a small Christian village. Founded as early as the 16th century, it stayed largely under the radar until it rose to sudden importance during the Oslo Accords, when it was declared “Area A” and placed under the control of the Palestinian Authority.

After the accords were signed in 1993 and 1995, several writers in exile, including Mahmoud Darwish, returned to the city. Mourid Barghouti came for the visit he chronicled in his lyrical memoir I Saw Ramallah. But the promised autonomy did not materialise. To many writers, Abu al-Hayat notes, Ramallah has come to represent the “glimmer of hope that isn’t real”.

‘Get out of my house’

One of the collection’s most wonderfully frustrating stories is Ziad Khadash’s "Get Out of My House", translated by Raphael Cormack. It begins when the narrator, a man named Ziad Khadash, walks into a house he thinks is his own. Inside, he is confronted by a woman who is “holding a kitchen knife and getting ready to scream.” He demands to know what she’s doing in his house, and she demands to know what he’s doing in hers.

Both parties are utterly convinced that this is their house, in what seems a clear echo of struggles over control of Palestine. They each point to different items as proof the house is theirs. When the woman pulls a passport out of a drawer, the narrator reads the name on it as “Ziad Khadash”, while she sees her husband’s name, “Ayman Sharif”. But when a police officer arrives to sort things out, he reads the name on the rental contract as “Samir Khaled”.

Finally, the landlord arrives - perhaps the ultimate authority figure. He says he rents the place out to a student named Fadi who is temporarily in Jenin. Our narrator leaves the contested house and quietly wanders through Ramallah, “smoking and waiting”. We are left walking the streets with him.

'Love in Ramallah'

Several of the stories tie autonomy to romantic love, including Liana Badr’s tender "A Garden that Drinks Only from the Sky" and Ibrahim Nasrallah’s infuriating and sweet "Love in Ramallah".

That story, translated by Mohammed Ghalaieny, could also be titled “Love in the Occupation”, for its interlinked tales of love, each shadowed by soldiers.

"Love in Ramallah" is set during the early Oslo years, and the first section opens when a young woman comes knocking on a door. Although she doesn’t know the man inside, she has read the play about his life and his years in an Israeli prison, and she wants to marry this romantic figure. The man inside, Yasseen, enjoys the idea of this woman who has fallen in love with his story.

In the second love story, an abusive sham romance is forced on two strangers. Yasseen is on a bus with his friend Na’eem when they’re stopped by Israeli soldiers at the Uyum al-Haramiya checkpoint outside Ramallah.

“There had never been a day when soldiers hadn’t been stationed at this spot,” the narrator tells us. “First it was the British soldiers; after them the Jordanian soldiers and now here we have the Israeli soldiers.” Na’eem quips: “One day we [Palestinians] will have a checkpoint here.”

For no reason, the Israeli soldiers fixate on Na’eem, refusing to let the bus through unless he kisses a young woman they have pointed out on the bus. “You Palestinians are always talking about making independent decisions,” the soldier says, pressing Na’eem to make a choice between stopping the bus and forcing himself on a stranger.

Yet when Na’eem refuses, the soldier won’t accept this “independent decision”. Instead, he strikes Na’eem with the butt of his rifle until the girl begs for a kiss and Na’eem concedes. At that, “the soldiers whooped, as if they were cheering for a winning goal scored by their team, while others grumbled in disapproval”.

In the third section, Yasseen gets off the bus and arrives at his auntie’s house, where the two have a conversation about love and social conventions. While she finds public displays of love slightly mortifying, he suggests it’s displays of war that should shame people.

Later, an army patrol arrives, parking near the house. Perhaps to distract the soldiers from her ex-convict nephew’s presence or perhaps inspired by their conversation, Yasseen’s aunt calls out to her husband: “I love you”. After a moment’s hesitation, her husband calls out that he loves her, too. The soldiers are suitably baffled. One says: “An old man, an old woman, shouting ‘I love you’ at each other. Crazy fucking Palestinians.”

'At the Qalandiya Checkpoint'

In her introduction, Abu al-Hayat describes the different routes by which one can approach Ramallah. If you’re driving up from the south, you will have to pass through Qalandiya checkpoint, she says, which separates Jerusalem from Ramallah. If you’re coming down from the north, you must pass through “similar, if less famous, checkpoints”.

In the stories, checkpoints are a constant presence. These are places of disappointment and cruelty, as with Naeem’s experience in "Love in Ramallah". In Liana Badr’s "A Garden that Drinks Only from the Sky", a woman is cut off from her beloved when checkpoints are closed, which seems to end their relationship. But they are also fodder for absurdist and dark humour, as in Khaled Hourani’s "Surda, Surda! Ramallah, Ramallah!" and Ameer Hamad’s "At the Qalandiya Checkpoint".

Set almost entirely around checkpoints, "At the Qalandiya Checkpoint", translated by Basma Ghalayini, begins with the narrator’s exasperated, “Here we go again. More waiting.” The narrator informs us that, “In total, a human is capable of spending 15 years at the Qalandiya checkpoint.”

But, the narrator tells us in a sarcastic aside: “They have flown in a team of anthropologists to create something useful from the time wasted at this checkpoint. A Norwegian study suggests salmon might be smoked in the fumes of checkpoint confrontations."

In this drolly satiric narrative, we learn that the narrator was born at a checkpoint, and that he saves his parents’ marriage by speaking his first word, mah’som - the Hebrew and Palestinian colloquial for checkpoint, thus distracting them from an argument. There is very little of Ramallah or any other city in this story. Indeed, hardly anything seems to exist beyond checkpoints.

The story’s core relationship is between the narrator and an Israeli officer he meets at a checkpoint. Like other characters in the collection, Hamad’s narrator is struggling for control over his world. While Yasseen’s aunt regained some control through her declaration of love, the narrator here regains some measure of it through his over-the-top humour.

So what sort of city is Ramallah? As Abu al-Hayat writes in her introduction, to many writers, it’s a dream that didn’t come true. But it’s also a living city that’s “always testing how far it can go, experimenting with what’s possible, and being judged in the process.” The stories, too, are pushing stylistic and narrative boundaries, seeing how far they can take their portraits of life in the city.

Ramallah is a small city, but as home to many of Palestine’s cultural and educational resources, it attracts people from all over Palestine and beyond. The Ramallah of this collection feels something like a big bus terminal, with people coming and going, confused about whose seat is whose, and where often travel is shut down entirely. And yet there are also moments of wicked humour, tender love, and elevating grace.

The Book of Ramallah is available from Comma Press

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.