Shams al-Maarif: Why is this mystic book feared in the Middle East?

To its defenders, it is an esoteric manual that may help those who read it get closer to God through the revelation of divine secrets. To its detractors, it is a compendium for dark magic that lures readers into the world of sorcery.

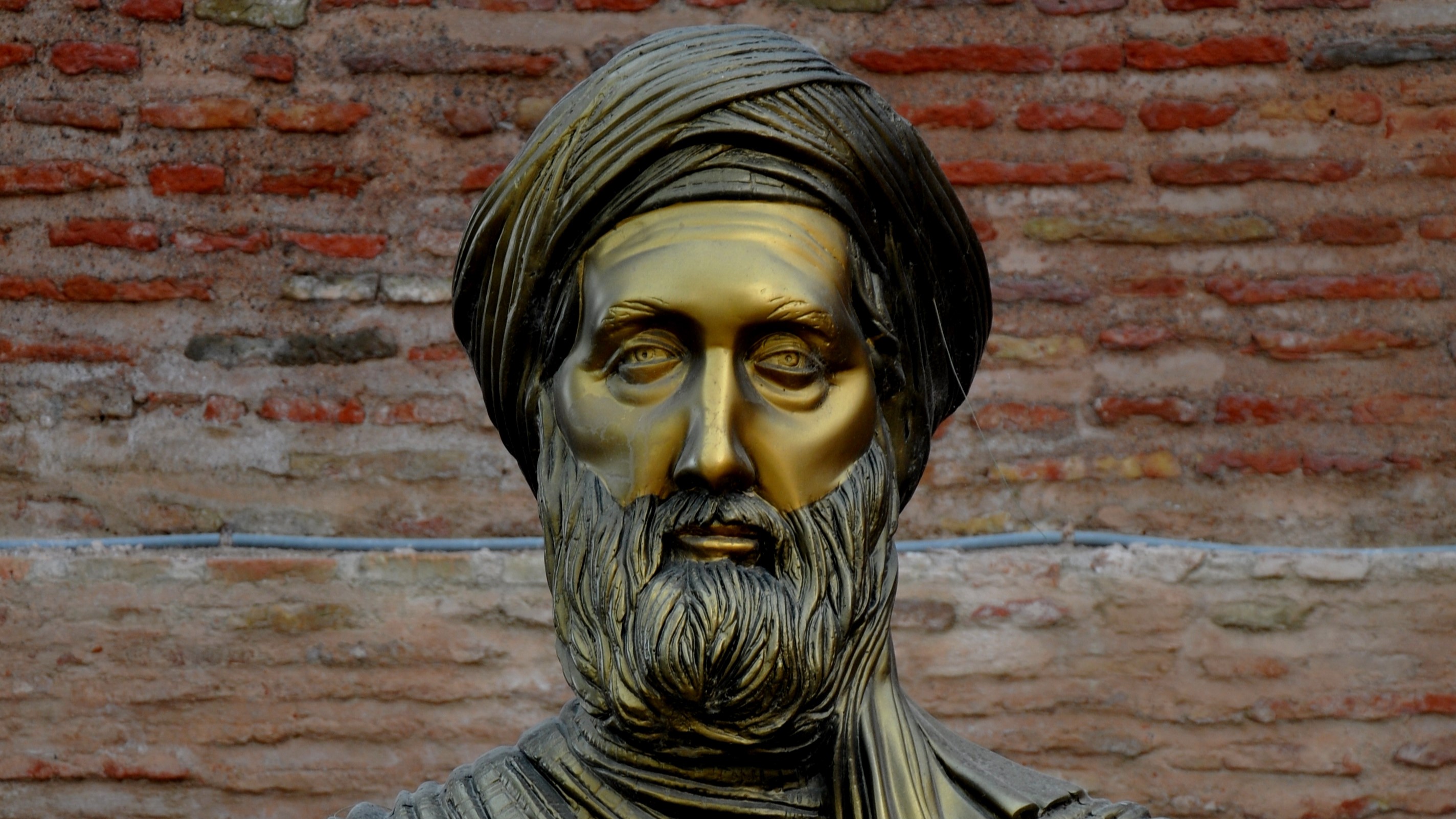

Shams al-Maarif - The Sun of Knowledge - was originally written by a 13th-century Algerian Sufi scholar, Ahmad al-Buni, and has been controversial in the Middle East for centuries.

While not all Sufis are fans of the book, the text does symbolise the fault lines behind mystic approaches to Islam on the one hand, and orthodox religious sources on the other.

For the latter, the Shams demonstrates the dangers of an obsession with the occult: one that can lead Muslims into the dark world of jinn, magic, curses and superstition.

The 99 names of God

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

According to the Sufi tradition, the words of the Quran, as well as other Islamic texts, contain an outward meaning, as well as a veiled one.

These hidden meanings reveal a truth that can be missed during a surface level reading of a text, and Sufis therefore invest a lot of time and effort in trying to fully understand their holy books.

While the Quran is the main focus of their meditations, so are the 99 names of God, known in Arabic as the Asma al-husna. For Muslims, these names describe Allah's different attributes, such as "Ar-Rahman", the merciful, and "Al-Khaliq", the creator.

Sufis believe that these names also carry a spiritual power that can be accessed through contemplation and meditative chants, known as dhikr.

Al-Buni’s Shams al-Maarif is a treatise on the properties and uses of each of God’s 99 names.

Every name he studies has a certain power associated with it, he writes, so reciting "Al-Alim" (the knowledgable) a specific number of times grants the believer access to divine knowledge, while reciting "Al-Qawwiy" (the strong) offers divine protection.

The Algerian-born scholar claims that the invocation of these divine names is what allowed miraculous events in Quranic history, such as the miracle of bringing the dead back to life and the ability of Jesus and Moses to talk directly to God.

The above claims are in keeping with mainstream Sufi beliefs.

The book becomes controversial, however, when al-Buni introduces his how-to guides on creating talismans using the names of God and a mixture of occult practices, such as numerology. There are charms and amulets for needs as varied as growing crops, increasing wealth, and finding true love.

Al-Buni also suggests ways to make contact with jinn and other supernatural beings - a decision that left him open to charges of sorcery from other Muslims.

Condemnation

By the 14th century, scholars like the sociologist Ibn Khaldun and the theologian Ibn Taymiyya, had declared al-Buni and his contemporary, Ibn Arabi, as heretics, dismissing their work as "sihr", or magic, which is strictly forbidden in Islam.

They cited the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad, who is reported to have said: “There are three who will not enter paradise: one who is addicted to wine, one who breaks ties of relationship, and one who believes in magic.”

But such condemnation was not enough to deter interest in the text, even amongst mainstream Muslims.

"His writings were criticised as sorcerous by a handful of premodern scholars, but despite that his works were widely copied and read up into the nineteenth century by highly educated, pious, and sometimes politically powerful Muslims," Noah Gardiner, an assistant professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina, told Middle East Eye.

"There's still a sizeable audience for his writings today," added Gardiner, who is writing a book on al-Buni and occult practices.

In his day, al-Buni was known as a theologian, a mystic, a mathematician and a philosopher.

He was considered a Sufi master and studied with the more recognised Ibn Arabi. They lived in an era in which mysticism was popular among Muslims and there were many other mystics with similar ideas, whose main purpose was to know God and to return to a primordial state of unity with the divine.

Al-Buni and others who studied cosmology and alchemy at the time would not have considered themselves to be magicians, but as those studying secret knowledge.

Given the secretive nature of the knowledge they believed they had access to, it is likely Shams was never meant to be seen by laymen but was instead meant for those initiated into Sufi orders.

Gardiner has written that al-Buni’s work was only “intended to be circulated amongst a closed community of learned Sufis”.

The book itself states: “It is forbidden for anyone who has this book of mine in hand to show it to someone not of his people and divulge it to one who is not worthy of it.”

Magic squares and summoning jinn

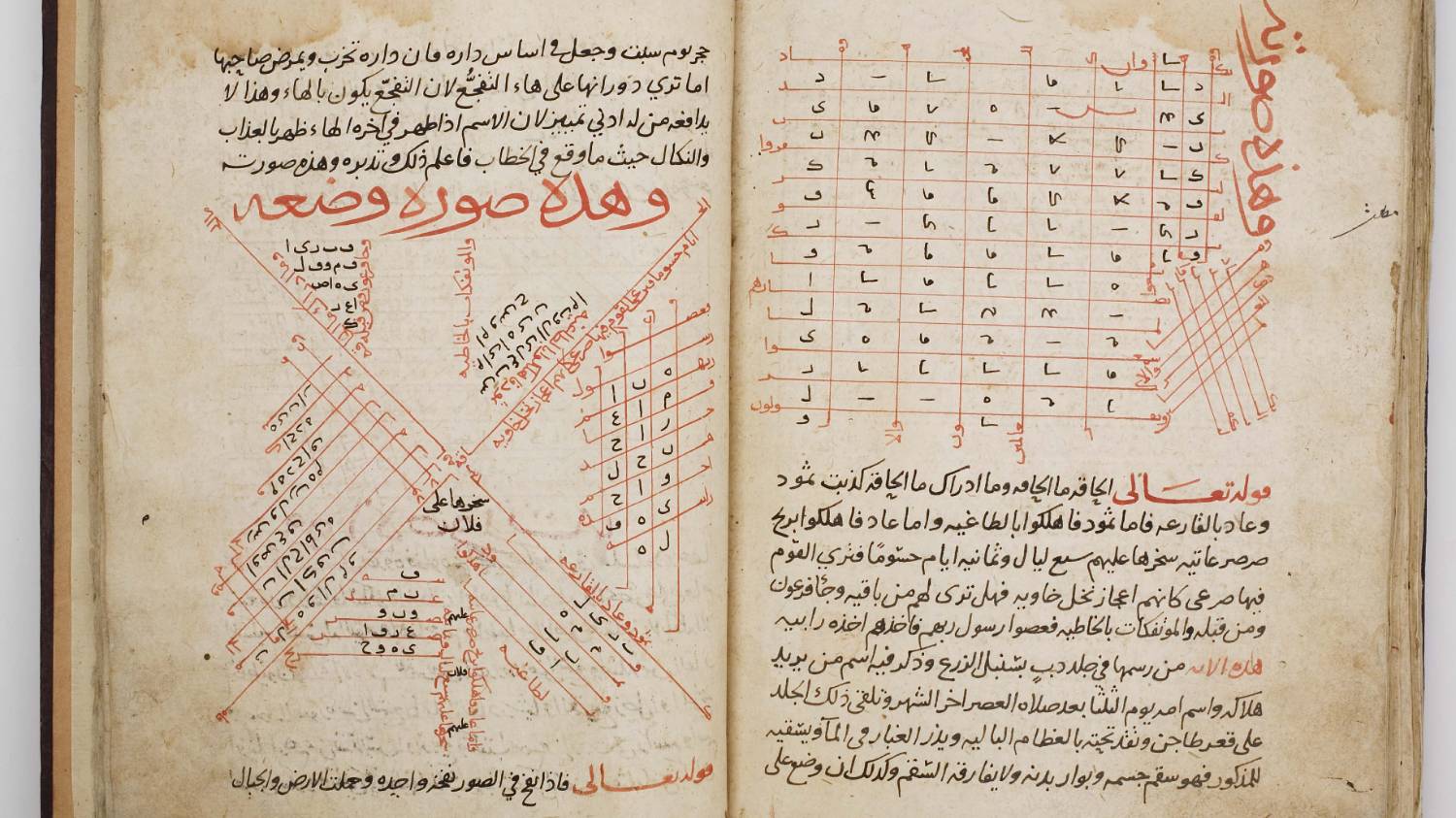

At just two chapters long in its first edition, the book is filled with colourful tables, prayer charts and numerological ciphers to help figure out hidden meanings, a study that became known as Ilm al-Huruf.

The mathematician theorised that the 28 Arabic letters of the Quran all have numerical values, an argument he made with reference to the mysterious letter combinations, known as muqatta'at, that open 29 of the Quran’s 114 surahs (chapters).

For example, the longest surah of the Quran, Al Baqarah (The Cow), starts with the letters "Alif, lam, meem" and Surah Maryam (Mary) starts with the letters: "Kaf, ha, ya, ain, sad."

The mysterious meanings of the standalone letters were seen as having properties that could fulfil the believer's wishes.

Using letters and numbers, al-Buni created elaborate charts, later described as magic squares, which were written in accordance with planetary alignments.

Magic squares had been used in places like India and Iraq centuries before al-Buni's era, but his work was one of the first cryptograms developed for a Muslim audience.

These ideas became popular amongst Sufis by the 15th century. They became so widespread that numerological charts were later copied onto the undershirts of soldiers in India.

Al-Buni also gives instructions on how to summon angels and good jinn to do one's bidding, with a caution that one may accidentally call upon a bad jinn.

Summoning jinn was said to be practised by Sufi masters, as their heightened spiritual state allowed them to serves as intermediaries between the spiritual and earthly worlds.

Urban legends and influences

After al-Buni’s death in 1225, a longer version of the book - written over several hundred years - appeared. Eventually it was 40 chapters long and with contributions from several anonymous authors, possibly hoping to popularise their own ideas by associating them with the authority of al-Buni’s original work.

"It's actually a patchwork of bits and pieces of al-Buni's authentic works, and texts by other authors," said Gardiner of the more recent compendium of Shams.

The newer version is known as Shams al-Maarif al-Kubra, roughly translated as the expanded Shams al-Maarif. Manuscripts from this edition don't appear in the historical record until the 17th century.

It’s this longer version that exists today and has been translated into Urdu, Turkish, Indonesian and Spanish.

Naturally, with its roots in the occult and the general taboo against magic and sorcery in Islam, Shams has given rise to intrigue and urban legends amongst Muslims.

In one story repeated on online forums, a Saudi man reads the book and marries a female jinn, who later kills his human wife, parents and parents-in-law.

For others, however, use of al-Buni's work is far more prosaic. In some some South Asian countries, like Pakistan and India, al-Buni’s charts sit in shop-front windows in the hope they help business.

His words, or variations, are also engraved into divination bowls in the region in the belief that water drunk from them can cure the sick.

Others visit pirs (Sufi leaders) or Sufi saints, who promise to cure the sick, marry off the single, and increase wealth, as long as they wear charms or amulets associated with al-Buni.

An English version of the the lengthier book was published in 2022 and is available online, where it’s described as “assist[ing] those unfamiliar with Islamic magic and culture”.

Debate continues to rage amongst Muslims on the merit of the work, with some describing it as blasphemous.

One review on Amazon reads: “Disgusting book which tells one about how to black magic - Very evil book - Can destroy your life by reading it.”

Another reads: “This book inspires black magic, to enslave jinns and this is all blasphemy. Please remove the listing.”

On the other side of the debate, in the comment section for a video about the book, one al-Buni fan calling himself a "certified spiritual healer", writes: “Shamsul Maarif is not a book of black magic. It's a book of wisdom and it explains the laws of the unseen world. The knowledge contained in it goes much deeper."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.