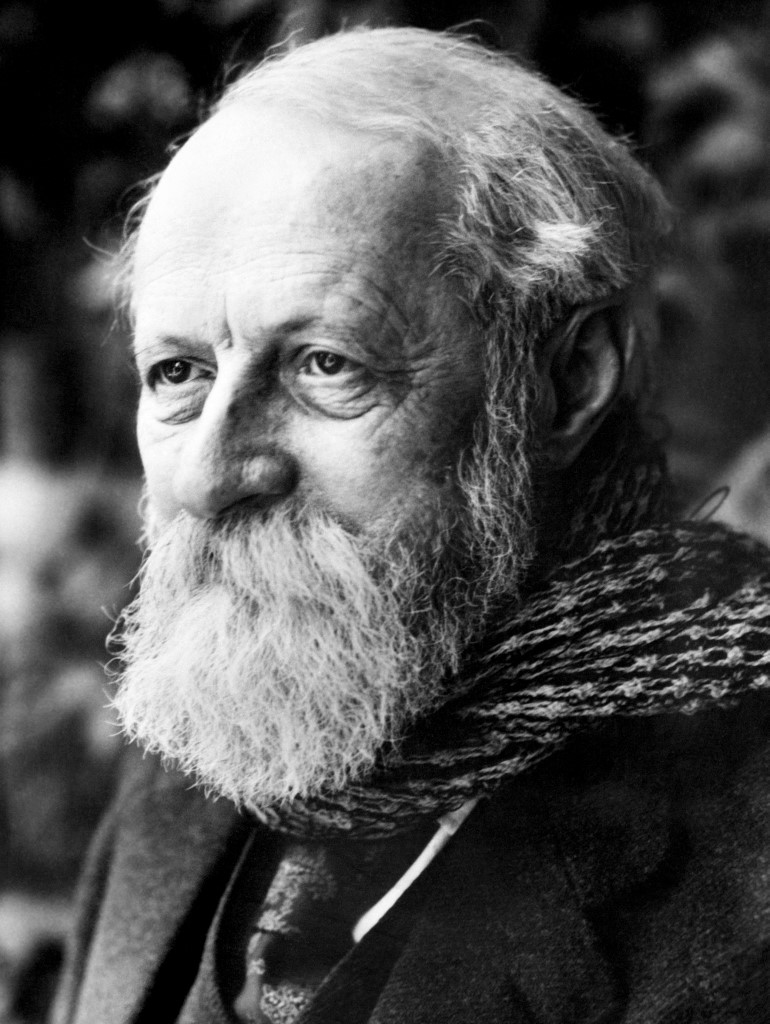

Israeli academic Shlomo Sand: ‘Jews and Palestinians will have to live together’

The academic Shlomo Sand's latest work, which is titled Deux Peuples Pour un Etat ? Relire l’histoire du sionisme in French (Two Peoples for One State? Rereading the History of Zionism), was written before 7 October.

However, the professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University told Middle East Eye he would not have “changed a theoretical line” if he had published it after the Hamas-led attack on Israel and the subsequent war on Gaza.

“Perhaps I would have specified that 7 October is a confirmation of my fears,” he clarified in a conversation with Middle East Eye.

“We can only move towards a political organisation of the two peoples in a federation or confederation. Otherwise, there will always be more disasters like 7 October and its consequences in Gaza,” he added, further cautioning:

“Before reaching this historic compromise between the two peoples, we will experience other disasters that will make this political solution indispensable.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In his voluntarist pessimism, the Israeli historian, who claims to be a realist and rejects utopia, remains convinced that Jews and Palestinians are "condemned to live together, otherwise they will disappear together".

"I do not think that a Jewish state alone can survive in the Middle East. No more than a Palestinian state, for that matter," he declares.

Having established this need for a binational state, the historian makes an appeal for Zionism. But not just any Zionism.

In his essay, the historian delves into forgotten texts by some early Zionists.

These thinkers thought out a binational state for Jews and Arabs, first within the Ottoman Empire and then Mandatory Palestine, even as the idea of an exclusivist Jewish national home was winning out.

According to Sand, Zionism created a “mythological circle” connecting the dispersal of the Jews mentioned in the Bible to the “return” of the Jewish people to “Eretz Yisrael” (the Land of Israel) in a historical linearity.

While there is this common thread tying Zionists of various kinds together, Sand considers Zionism a pluralist movement.

A Eurocentric ideology

Sand writes that it was the version of Zionism promoted by its founder Theodor Herzl and of the leaders of the newly created state of Israel that eventually imposed itself to the exclusion of other forms.

"They are the ones who shaped Israel as in a power struggle with the Arab world," he told MEE.

This sort of Zionism was very much influenced by European Orientalism.

The Zionism of Herzl and Vladimir Jabontinsky, the chief ideologue of the Zionist right, won the ideological battle in Israel.

‘We can only move towards a political organisation of the two peoples in a federation or confederation. Otherwise, there will always be more disasters like 7 October and its consequences in Gaza’

- Shlomo Sand

It was an ideology deeply rooted in a European vision of the nation-state, one which had a racial dimension, required a demographic majority and was permeated by European colonialism and orientalist thinking.

Herzl thought of the future Jewish state as a western outpost in Ottoman Palestine.

Jabotinsky denied the natives of Palestine any possibility of agreeing to a Jewish presence and instead promoted the use of force to impose the Zionist idea.

Their ideas filtered down to Israel's founders.

Its first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, for example, was obsessed with securing a Jewish majority for the young Israeli state.

All three shaped thinking in modern Israel.

Israel's founder asserted a fierce refusal to establish a political structure based on the democratic principle of "one person, one vote" that would risk hindering Jewish colonisation.

Sand’s book also shows how Zionism was very much influenced by a persistent Christian antisemitism.

The historian writes that the idea of "natural" ownership of Palestine had been favourably welcome in the Christian Western world, in particular because it implied the promise of a decrease in the number of Jews in Europe.

The forgotten fathers of another Zionism

While working on his book, Sand said he was surprised to discover other currents of Zionism that called for a binational state.

“They rejected the idea of an exclusive Jewish state, because they knew Ottoman or Mandatory Palestine, having lived there.”

These proponents of a binational state were both idealistic and pragmatic, he told MEE.

The book is peppered with names like Ahad Haam (a pen-name of author Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg, meaning, "one of the people"), Bertrand Lazare, Gershom Scholem, Martin Buber, Albert Einstein, Hannah Arendt, Avraham B Yehoshua and Uri Avnery.

Essayists, Jewish scholars, writers, philosophers, they put forward a vision of a binational state.

Most of them are known in Israel as the proponents of a so-called "spiritual" Zionism, deeply influenced by Jewish ethics and religion. A large number of these "spiritual" Zionists were religious, unlike the atheists Herzl, Jabotinsky or Ben Gurion.

Their writings on the binational state are little known, Sand told MEE.

“Their theories devoted to the Arab natives have been eclipsed and only those where they linked Zionism to the religious texts of Judaism were preserved.”

For these other Zionist thinkers, attached to the idea of a binational state, Mandatory Palestine was a Semitic place and not a western outpost in the Orient.

These thinkers had observed a populated land, contrary to Herzl’s slogan, “A land without a people for a people without a land.”

They themselves felt deeply Semitic and saw in the “return” to Palestine a way to rediscover their lost orientality.

“Surprisingly, these thinkers who campaigned for a binational state also saw the Jewish people as a race. And that is precisely why they thought that one could get closer to the Arabs, because they were the same Semitic race,” Sand explained to MEE.

“For them, the Jewish people were Semitic and had to live with the Arabs, in the hope of a Semitic race that would once again be unified.”

These “Semitic” pacifists found many points of convergence, both spiritual and biological, with the Orient and the Arabs, Sand notes in his book.

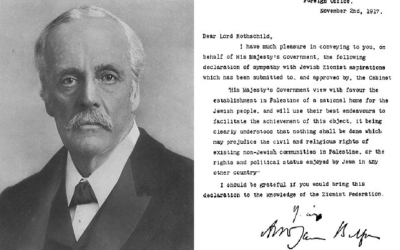

And unlike Herzl, for example, some of them were quick to reject the Balfour Declaration, which guaranteed the creation of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Ottoman Palestine, seeing it as a show of imperialist force.

For some of these figures, the residents of Palestine even represented the descendants of the Judeans who were Islamised after the Arab conquests.

Sand devotes meticulous and detailed pages of his book to these thinkers of a Semitic binationalism.

He mentions Haam, who joined Zionist movement in the 1880s and had travelled to Ottoman Palestine, lived there and learnt Arabic.

‘I can see clearly that the Israeli state, as it defines itself as a Jewish state, will not survive’

- Shlomo Sand

The reader also discovers the Brit Shalom ("covenant of peace") group, created in 1925, which wanted to be the bearer of an ethic, which consisted of living in Palestine together with its people, without any desire to replace them.

Amongst its members were Buber, Judah Leon Magnes and Einstein, who conceived of a state for two nations, with perfect equality of rights, regardless of any question of demographic superiority.

In this binational state, the holy places would have been in a situation of extraterritoriality and there would have been no place for state religion.

Other thinkers traverse this rich and fascinating essay, such as the Ihud (“unity”) movement, founded in 1942 by Magnes and Buber, and Semitic Action, founded by Avnery in 1956. The latter defended “Canaanism,” or the idea of a nation founded neither on Jewishness nor Arabness, but on binational coexistence.

As for Yehoshua, he saw in the “Israeli being” the first expression of the self-determination of the Jewish man. The Israeli writer imagined a citizenship detached from religion.

A voluntary pessimism

Sand’s work also illustrates his own evolution as a historian and an Israeli. A long-time advocate of a two-state solution, Sand explained that reality convinced him that only a federation or confederation had become viable.

The historian wants to be pragmatic. “I started reading [these authors] because I was losing hope in empty Israeli or international slogans, like ‘the two-state solution’, which do not correspond in any way to the reality on the ground,” he told MEE.

He also felt some weariness in the face of the “tragicomic play” of a peace process that never came to a successful conclusion.

There is a gap, he said, between empty and abstract political speeches on the one hand, and the actual reality of an already binational state on the other.

He therefore established a connection between the analyses of Arendt, who predicted that an exclusive Jewish state would face a war every ten years, and his everyday life in Tel Aviv: “I can see clearly that the Israeli state, as it defines itself as a Jewish state, will not survive,” he reiterated.

Sand also explores his memories as a young soldier, demobilised in 1967, in the midst of the euphoria generated in Israel by the conquest of Jerusalem.

“As soon as '67, I started calling for a Palestinian state alongside an Israeli state,” he said.

“I almost died during this war. In Jerusalem, I joined those who criticised the Israeli government. Then I turned to the radical left because I was convinced that there was no future with the occupation,” he explained.

Contrary to the messianic and nationalist inebriation that seized Israel, the right to self-determination for the two peoples between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan river serve as his “guideline”, Sand writes.

Since 1967, the West Bank has been occupied by more than 875,000 settlers. Four ministers of the current government and a chief of staff even live there. That undermines any viability of a two-state solution.

“We are de facto in a binational state,” Sand insists.

“We are now so irreversibly intertwined with each other that, deep down, I tell myself that the occupation that began in 1967 revealed [the state] that could have happened in 1948 [during the Nakba], if there had not been the expulsion of 700,000 Palestinians.”

'We are de facto in a binational state’

- Shlomo Sand

On the Palestinian side, a large part of the population lives under a regime that he describes as apartheid.

“The public mobilisation to defend the Israeli democracy has not in the least mentioned that for 56 years, several million Palestinians have lived under a military regime and are deprived of civil, legal and political rights,” he writes.

This situation is unsustainable, he told MEE.

In addition, the Palestinian Authority does not have popular support, according to Sand.

The Israeli thinker notes that there have been no elections in the occupied West Bank or Gaza for years and the Palestinian Authority depends politically, socially, and economically on Israel.

“I therefore came to the conclusion that it was necessary to transform a de facto situation into a de jure situation. The most important thing in a de jure binational state is equal rights. One man or one woman equals one vote,” he told MEE.

Collective rights

Sand advocates giving communities rights that ensure the respect of the principle of equality. Each community must be able to keep its religious, cultural and linguistic specificities.

The historian looks at effective models, such as Switzerland, Belgium and Canada. “Concordance democracies” in which individual rights are recognised, but also where collective rights are allocated to different linguistic communities.

“Obviously, thinking about all this after 7 October is even more complicated. But hatred brings nothing. All conflicts have an end. We have no choice. We can live with the Palestinians because, in fact, we already live with them,” he said.

The only thing that could stand in the way is what he calls “the symbiosis between nationalism and religion”.

This phenomenon, which did not start on 7 October and can be observed both in Israel and amongst the Palestinians, threatens the hypothesis of a binational state.

Sand is also worried about Israeli public opinion.

“The watchword is security first and foremost. Besides, the Israelis do not know the Palestinians, while the contrary is not true. Israelis do not speak Arabic, whereas Palestinians generally learn Hebrew."

Sand's voluntary pessimism also names two fears: "October 7 contributed to the rise of antisemitism. I also wrote this essay to prevent people from becoming antisemitic."

The other fear is a new expulsion of Palestinians: "What happened in 1948 can be done again," he wrote, as if trying to ward off this possibility.

Deux Peuples pour un Etat ? Relire l’histoire du Sionisme was published in French by Le Seuil in January 2024. It was translated from the Hebrew original, called Israel-Palestine: Reflections on Binationalism, which was released by the Israeli publishing house Resling in 2023. An English translation is expected in September under the title Israel-Palestine: Federation or Apartheid? (Polity Press).

This article was translated from MEE French edition (original).

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.