This 12,000-year-old town could soon be under water

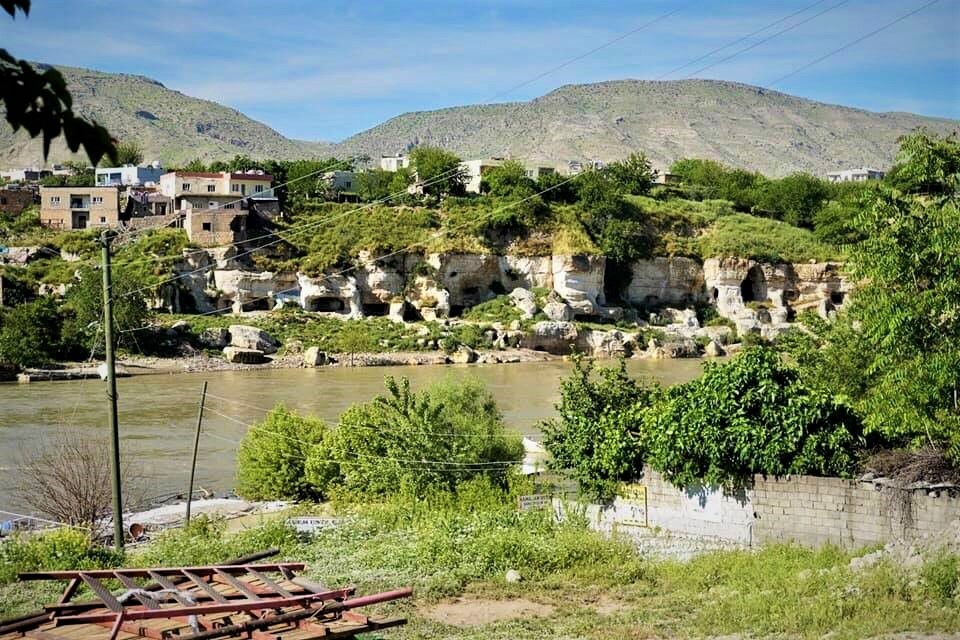

Abdurrahman Gundogdu looks out from his gift shop across the street and towards the slow-moving river Tigris, which has flowed through Hasankeyf throughout its 12,000 years of human habitation.

But not for much longer.

If the flooding of this ancient town goes ahead as planned, as the controversial Ilisu dam is filled, lifelong resident Gundogdu will be gone, along with 3,000 other inhabitants.

Nearly 200 villages will be completely or partially flooded, impacting around 100,000 people, according to local campaign group Initiative To Keep Hasankeyf Alive.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

They will be the last generation of the hundreds who have lived and died here in the world’s oldest continuously inhabited town, known to have been settled for 12 millennia.

“Allah gave this space to us like this; the Tigris is mentioned in the Quran,” Gundogdu said, his hand sweeping out to indicate the place he loves.

Even though he dreads the day he will have to move to the new town built for residents by the government, he says he has given up the fight to save Hasankeyf, or the river. “I have no more hope, unfortunately. I tried but couldn’t make it happen.”

The floodgates were shut in late July so that the waters behind the dam began to rise, giving residents and campaigners a few more precious weeks and months to try to halt the inevitable.

Despite numerous public demonstrations and a number of police arrests of protesters, activists continue to try to convince Ankara to suspend the project.

Ilisu dam - energy, jobs

The Ilisu project aims to produce 3,800 gigawatt hours of electricity annually to the Batman region in southeast Turkey, and is expected to generate 1.3 billion Turkish liras ($227m) annually.

Sitting 140 kilometres away from Iraq, Ilisu is a key dam among 22 built as part of the Southeastern Anatolian Project, or GAP - a national development policy that includes regional irrigation, employment and energy needs.

It’s the country’s second largest in volume and fourth in energy generation according to the Turkish government.

It will also significantly impact Turkey’s neighbours since the Tigris flows into Syria, enters Iraq, and reaches the Gulf after merging with the Euphrates.

But since construction began in late 2000s, Ilisu has been dogged by controversy.

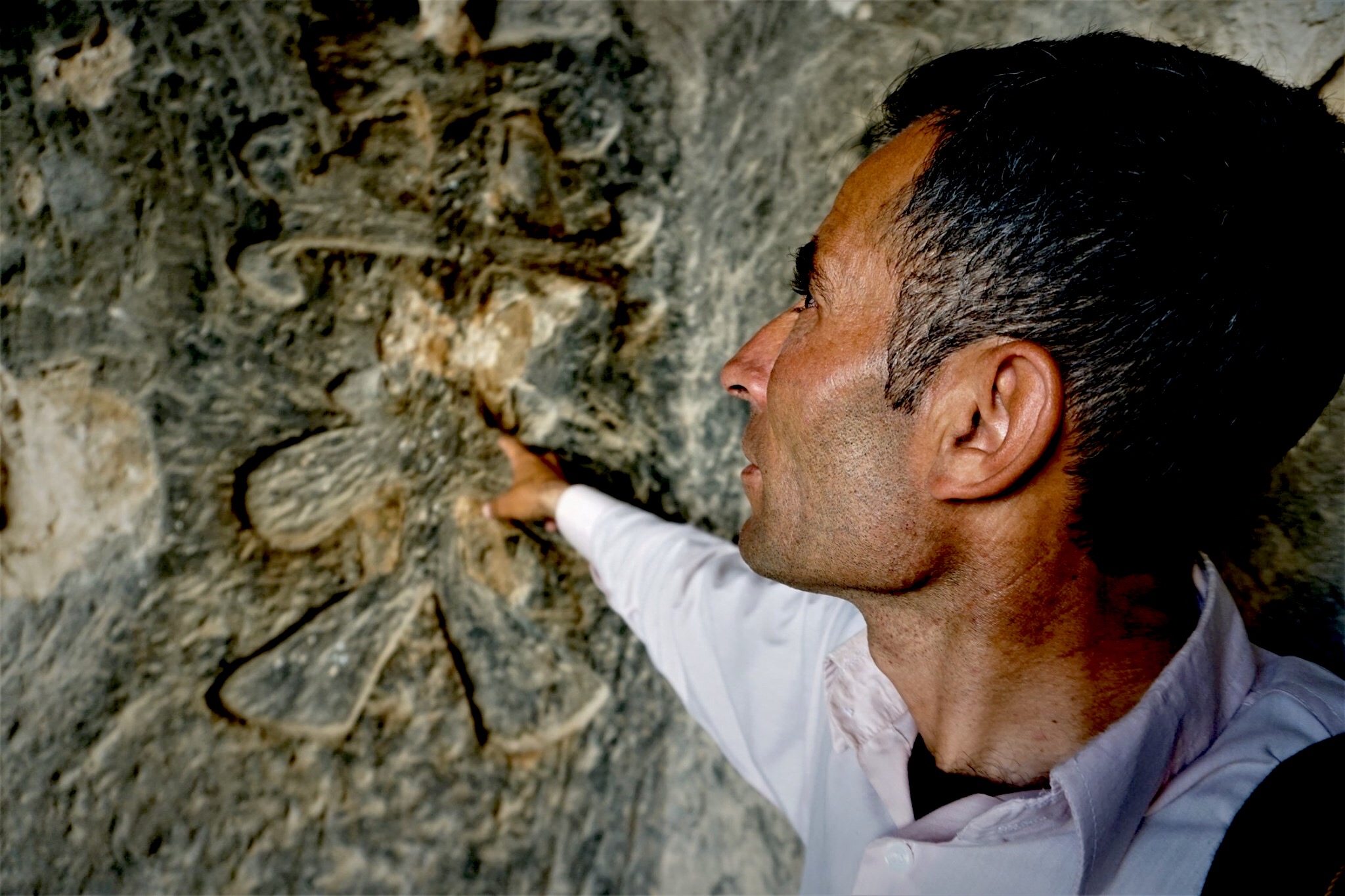

Over the years international NGOs, environmental groups, and European politicians warned that it would submerge a unique site of human heritage, destroying hundreds of archaeological treasures, including more than 5,000 archaic caves built along the river, and submerging the birthplace of several major civilisations.

Despite vocal opposition and major protests, the project eventually went ahead with strong support from Turkey’s AKP government.

Back in 2003, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, then a newly elected prime minister, vowed to embark on a number of mega projects to solve an economic crisis and bring prosperity to Turkey’s poorer regions.

In 2006, he held a ceremonial groundbreaking in Hasankeyf and said there was no time to lose on the construction of the dam. “With Ilisu, a cornerstone will be placed among the civilisation stones of the southeast," he said, addressing crowds.

In 2008, the first spade was dug. Finally, it was this very site that was blown up using dynamite in August 2017, to help erect Ilisu’s 64-metre-high concrete walls over the fertile river basin.

Unique structures

In Hasankeyf, local tour guide Ali, known as Shepherd Ali, has noticed how the turmoil of the construction and removal of so many historic edifices has not just had an impact on local people.

For centuries, the town’s tallest structure, standing at 30 metres, was the iconic minaret that topped the early 15th-century El-Rizk Mosque overlooking the Tigris.

Often the background image for tourist pictures, it was dismantled over the winter.

“The regular stork was offended,” said Ali. The stork would go to find its old perch on the minaret, he explained, as he walked through New Hasankeyf amid dust from ongoing construction. But the minaret was gone - taken to be relocated in the new town.

“It came a few times after it was taken down, then it gave up.”

Hasankeyf is home to some 500 structures of historical significance, built by the various empires and civilisations that ruled this part of Mesopotamia, including Hittites, Romans, Persians and Ottomans.

To preserve some of the most significant, the authorities have dismantled, transported and rebuilt them in New Hasankeyf, around three kilometres from the old town.

The minaret is one of seven big artefacts that were removed from the old town, alongside 785 out of 1150 graves from the old cemetery.

The 1,100-tonne Zeynel Bey Shrine, the only remaining structure from the 15th century Akkoyun state, was also relocated, carried on wheels for three hours to the newly built archeopark, placed right in front of the new housing complex.

Ali said he defines the uprooting of these iconic structures as “plucking the flower”, adding that he thinks “a rose is best on its branch”.

He also does not want to move to the bland, concrete town built for Hasankeyf residents, despite Ankara’s offers to include a museum, a mosque and parked boats on the water.

“But I have to leave when the time comes,” he said.

Poor construction

The government has promoted the dam and the new town as critical for a region that has been long neglected and hit by the conflict with the Kurdish separatist PKK, which raged here for decades.

The Batman region where it sits has the highest unemployment rate in the country, according to official figures. At least a quarter of its locals are jobless.

Hasankeyf resident Ahmet Akdeniz was once a big supporter of the project - but not anymore. “I really supported this project to help our people get better living conditions. Some of us were living in caves,” he explained.

He used to be one of its best known advocates from Hasankeyf, travelling to Europe to defend it from its many critics. He once asked German MP Claudia Roth “why she was so worried about dislocating history here and not when it comes to pieces in [Berlin’s] Pergamon Museum.”

“If the project was installed properly, it could have been really beneficial,” he said.

But Akdeniz became disillusioned with the new housing project for relocated residents. “The walls leak water.”

Middle East Eye saw the leaks from the walls in the new homes, 850 of which were built by Gunestekin Construction in partnership with Sertka, another builder.

A project manager from one of the companies told MEE that the leaks are the result of the dynamite explosions nearby.

“We told authorities repeatedly, but they say that there’s not much they can do. The explosions every other day are causing us big losses because we keep repairing,” Yuksel Durak from Gunestekin said.

Yet at this point, residents don’t have other options. They have to leave their homes and buy one of the new ones if they wish to stay in the area, across the Tigris. The new houses cost 170,000 Turkish liras, around $30,000.

Locals can start paying the government in five years - but some say they can’t afford that amount.

“We are poor people. We’ve always been poor,” Mehmet Basak, a Hasankeyf native, said.

New homes for some

Others say they have not been offered homes in New Hasankeyf because they do not qualify under the government scheme.

Basak said neither he nor any of his four siblings were given houses as they are registered as living in central Batman, even though he has a house in old Hasankeyf and was born there.

This is because of the Settlement Law, according to Abdulvahap Kusen, mayor of Hasankeyf for 20 years.

According to the mayor, under law 5543, only families who were registered as living in Hasankeyf on 1 April 2013 are eligible for housing. Basak's family and others like him will instead have to move to new homes in central Batman.

“They left Hasankeyf natives homeless by giving the deeds to foreigners, people in their close circles,” Basak claimed. He said he has 12 children and 10 grandchildren who do not know why they were not included in the new settlement.

Basak said he did not blame President Erdogan “because he doesn’t know what’s happening here”. Still, he noted that Erdogan’s party, the AKP, lost his vote.

Kusen, from the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), told MEE by phone that the displacement is not forced, but “they will have to leave when the flooding begins anyway”. He then hung up.

The psychological toll of abandoning Hasankeyf comes up again and again in conversations along the Tigris.

Shepherd Ali said he has lost significant weight over the years campaigning against the dam project, while shopkeeper Gundogdu says he has been using antidepressants for years to help with moodiness, crushed by the idea that he is losing his hometown.

They both said they wish they were asked about the fate of their towns, and not forced to leave.

The culture minister

One person who should know whether all the environmental and heritage costs of the project were properly assessed in the planning of Ilisu is Ertugrul Gunay.

Turkey’s culture minister between 2007 and late 2012, he told MEE his ministry held many meetings with the Forestry and Water Affairs Ministry, offering to save Hasankeyf during that period, but to no avail.

“[The ministry] told us that these demands are impossible to meet, that things had gone too far out by now,” Gunay told MEE, adding his teams carried out scientific excavations in a bid to preserve ancient Hasankeyf.

The right to grant Environmental Impact Assessments (CED) was taken from his ministry in 2011, he said, and was given to the Environment, Forestry and Urbanisation Ministry, which at that time oversaw state hydraulic works.

CEDs are mandatory state-approved permits for major projects like dams, now granted by the Ministry of Environment and Urbanisation after the restructuring of the ministries since 2011.

Ilisu was greenlighted by the Ministry of Environment and Urbanisation in 2011, and granted an exemption. Linked construction involving roads and bridges were exempted from CED in 2012.

In 2013, the Council of State overturned the exemption decision on Ilisu, but the construction continued, NGOs said and local media reported.

“Dams, water and energy have been seen as the country’s top priorities by almost all its governments,” said Gunay. “That’s why, as investment projects were developed, settlements, natural and historic assets always came second.”

He said he doesn’t have regrets because things were out of his hands. But he said pointedly that former prime ministers should be regretful about the haste with which the project was realised.

Gunay also conveyed his observations that Erdogan was hasty to realise the project.

‘We saved Hasankeyf’

Yunus Bayraktar has no doubts about Ilisu - he has been here from the start of the development, and said the dam project and transformation of Hasankeyf was his master plan.

As a key Ilisu project coordinator for Nurol Construction, the Ilisu development consortium, he vows Ilisu is here to improve life for local people.

'We came to offer employment to the region and improve the lives of Hasankeyf’s locals, some of who were living in caves, but it was the world’s NGOs against us'

- Yunus Bayraktar, Nurol Construction

He said he went there and stayed in a tent for a week in 2003 with a comprehensive team and mapped it out. The locals were living in extreme poverty, he said.

Now, “they will get to live where hotels will cost $500-$700 nightly”.

According to Bayraktar, the consortium wanted to bring development and prosperity to Hasankeyf but faced a battle with the international NGO community that opposed the project.

“We came to offer employment to the region and improve the lives of Hasankeyf’s locals, some of who were living in caves, but it was the world’s NGOs against us,” he told MEE.

Many protests were organised around the world and in Turkey to save Hasankeyf by groups opposed to the development, including one that saw him and other members of the construction team surrounded in 2005.

“Guards set up a human wall and that’s how we escaped (demonstrators),” Bayraktar said, referring to the incident in Turkey’s southeastern Diyarbakir province. “We fought against the world for this project for years.”

He noted he spent half of his four years in his post between 2003-07 in Europe, trying to make his case globally.

“We saved Hasankeyf,” he added.

Habitats at risk

But that is not the view of environmentalists. They see the dam and construction project as threatening an entire ecosystem in Hasankeyf.

Advocate group Hasankeyf Matters said that endemic species, as well as much of the town’s undiscovered biodiversity, faces urgent threat with the planned flooding.

According to John Crofoot, the NGO’s co-founder from the US and a part-time Hasankeyf resident since 2006, there’s much to lose. “The ecosystem is so extraordinary, it prompts newcomers to feel the magic instantly,” he said.

There are rare medieval gardens in Hasankeyf that have been critical to Islamic architecture and are now endangered, he added. “Even Konya doesn’t have such gardens. I can’t believe they want to lose that,” Crofoot told MEE.

But it’s more than the gardens that are at stake with the dam.

“Of the approximately 470 bird species known in Turkey, more than 130 have been observed in Hasankeyf. Twenty-five of these are threatened,” according to a statement by cultural and natural heritage conservation group Europa Nostra.

It continued: “The Ilisu reservoir would eliminate the steep soil slopes next to the river, which are used for nesting by the pied kingfisher (Ceryle rudis), one of the most endangered riparian bird species in Turkey.”

Previous mega constructions have caused major loss of habitats for rare species.

Environmental groups point to the activation of the Birecik Dam in Sanliurfa and the resultant problems the Euphrates River suffers from today as a clear warning of what is likely to happen to the Tigris once Ilisu is fully operational.

The endangered Bonelli’s eagle lost its breeding ground in Halfeti after the Birecik dam was built.

Now the Euphrates softshell turtle, the Mesopotamian barbel and the Diyarbakir spined loach face similar danger because of Ilisu.

The ecological warnings also come at an alarming period, as the Tigris-Euphrates Basin registers the second fastest rate of lost regional groundwater storage, according to Chatham House.

“We come down by the water to drink from it,” a Turkish song played on the bus to the town goes, one of many dedicated this region’s fresh water.

The rivers matter greatly for the local culture, which is mainly Kurdish, and was once widely shared by Syriacs, Armenians and Chaldeans in earlier times. Dicle, meaning Tigris, is a common name across Turkey.

Lack of Unesco protection

Despite its unique cultural and ecological heritage, Hasankeyf does not enjoy Unesco protection, points out environmental engineer Ercan Ayboga.

This is all the more remarkable given that it qualifies for nine out of 10 of the international heritage body’s criteria, explains Ayboga, the spokesperson for the Initiative to Initiative To Keep Hasankeyf Alive.

“There are sites that meet only one and get admitted,” he adds.

Unesco has stated it needs the Turkish government to apply to get Hasankeyf admitted to the heritage list, and said Turkey has not made an application in this regard.

Meanwhile, the European Court of Human Rights dismissed the appeal defending the town in February - an objection brought by five advocates; three professors, one lawyer and a journalist. After 12 years of evaluation, the ECHR said the matter exceeds its jurisdiction.

Ayboga said ECHR was “hiding out” with that decision while Unesco had failed to act.

“Turkey’s presence on the heritage committee seems to pressure Unesco, but that doesn’t mean Unesco can’t do more than just watch,” he said. “They can campaign.”

However there is only so much the world heritage body can do without official support from Turkey. “Unesco doesn't have a legal basis to take sides in this debate,” a Unesco official told MEE.

For a site to be considered for the World Heritage List, the member state would have to submit a nomination application, its website says.

Corporate power

While many locals are now resigned to moving out of Hasankeyf before it is submerged, in Istanbul campaigners against the dam have not given up. They still believe the town and the Tigris that flows through it can be saved, even at this late stage.

In Istanbul’s Taksim district on 25 June, more than 20 artists got on stage to amplify this message.

Neslihan Aksunger, a Hasankeyf advocate originally from the eastern Erzincan province, doesn’t believe the project aims to bring sustainable wealth to the people of the region as the official texts state, promising jobs, prosperity, gondola rides for tourists and pond fishing.

“Of course energy is important, but the government should seek and find other ways to provide that service to the public,” she said. “We know who wins here.”

“Was that the case in eastern Black Sea?” Aksunger said, criticising the hydroelectric power plants that have damaged natural habitats in the evergreen mountainous north.

Since 2010, at least 203 hydroelectric power plants similar to Ilisu were built in Turkey’s Black Sea region. Many sparked a backlash from locals and environmentalists, who defied the projects endangering the country’s rare green zones. Some of those fights were won.

Dogu Eroglu, an investigative journalist who closely follows the environment beat in Turkey, said Ankara supports mega projects in energy and urbanisation that irreversibly change the local lifestyle and culture – and the reason is, he said, to cultivate state-corporate links.

“Mega projects enable the state’s capital transfers to take government-company relationships beyond the projects at hand. And in the future, the companies who hold the bids may be asked to take on certain roles in the government's favour,” Eroglu said.

“Which means that the central government is not buying electricity, but hopes to find itself new partners.” That is why, he said, finding alternatives to these mega projects does not fit the government’s goals. “They’re not really interested.”

The Ilisu consortium, which previously included German and Swiss companies, fell apart in 2009 after worldwide protests over environmental and cultural concerns and worries over the locals’ human rights. Then, private Turkish banks Garanti and Akbank, and state-owned Halkbank took over the financial burden.

Cengiz Holding - one of the three major Turkish groups involved in Ilisu alongside Nurol and Temelsu - was handed 7.9 billion Turkish liras ($1.38bn) worth of tenders in 2017.

Known to be close to the government, Mehmet Cengiz’s conglomerate saw the sum of tenders it won between 2011 and 2017 increase ten fold.

According to data provided by the World Bank Group, five out of ten companies that got the highest infrastructure bids from governments between 1990 and 2018 come from Turkey. Cengiz is one of them.

What’s the alternative?

But apart from stopping the dam through protests or legal action, could something else be built in its place that would benefit local people?

At the concert for Hasankeyf in Taksim, as eclectic music is played with songs sung in several of Turkey’s minority languages, videographer Omer Kara said a different kind of energy project could save the site.

“Hasankeyf is a great place to lay solar panels thanks to the sun there. They don’t have to destroy the environment or an ancient site to generate electricity.”

And it’s not just activists who are saying this.

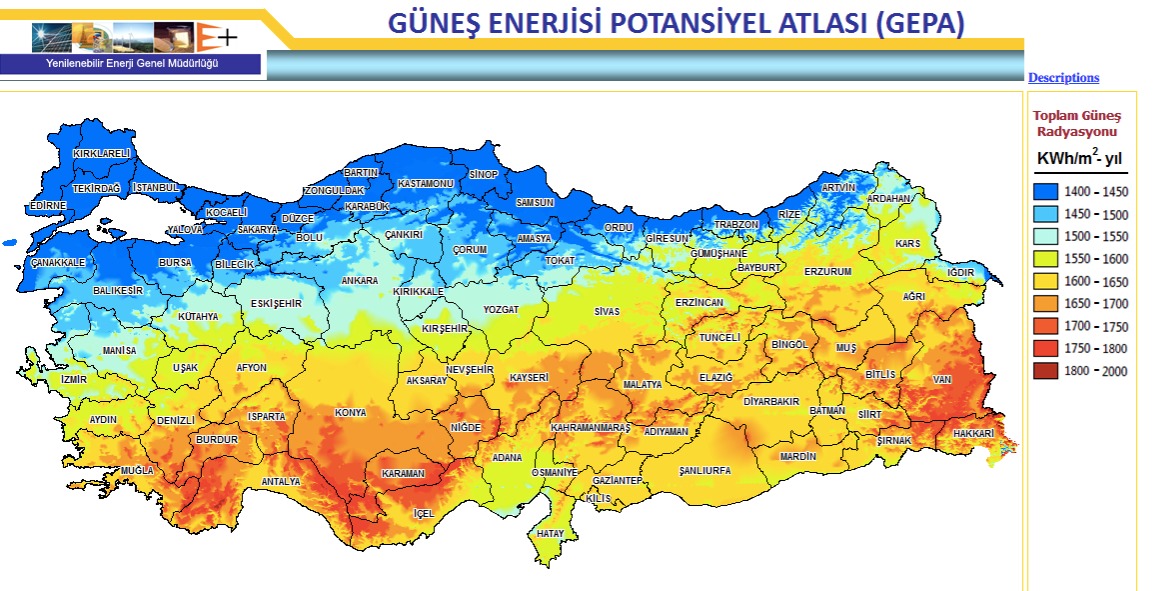

The Energy and Natural Resources Ministry’s Solar Energy Potential Map (GEPA) shows Turkey’s solar energy generating potential across all 81 regions, with hotspots near the dam zone.

Could a comprehensive solar energy project provide energy on the scale that the dam aims to in Hasankeyf? The Turkish Mechanical Engineers Chamber’s Energy Study Group examined the question and came up with a startling answer.

Their results show that with solar panels in Hasankeyf, it is possible to generate the same amount of energy as Ilisu, using one-ninth of the dam’s area, and with minor if any historic or ecological destruction. Plus, solar is cheaper than the dam, which has cost 12 billion Turkish liras, according to officials.

'Hasankeyf is a great place to lay solar panels thanks to the sun there. They don’t have to destroy the environment or an ancient site to generate electricity'

- Omer Kara, videographer

The chamber released an analysis with the calculation exclusively for MEE and explained such infrastructure projects are basically pointless – that Turkey already has more than enough energy.

“While power consumption was 303 GWh in 2018, the Energy and Natural Resources Ministry states that 450 GWh of power can be produced using current systems,” the statement said.

Adding that there are plants still in the early phases of construction, by 2024, Turkey is set to massively exceed its needs in power production, the chamber added, and said the supply is 45 percent overcapacity.

“All these numbers show us is that neither the Ilisu plant that is destroying Hasankeyf nor the nuclear plant projects are out of necessity. The ruling government transferred 32.4 billion Turkish liras to the private sector by using energy policies in 2018.”

In Hasankeyf, Mehmet Basak lamented the fact that he is losing his ancient home and is not getting a new home to replace it. “We spent our entire lives here. This is basically torturing people. Isn’t it a shame?”

Only the next few critical months will tell if Hasankeyf, its residents, hundreds of ancient sites, and the river Tigris, will get a last-minute reprieve.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.