Omar: The opera that tells the story of an enslaved Islamic scholar

The year is 1807, and Britain has passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, outlawing the British Atlantic slave trade. A year later, the United States follows suit with legislation outlawing the importation of slaves - but still, the domestic slave trade continues at its ports.

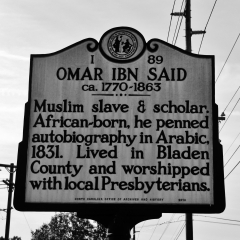

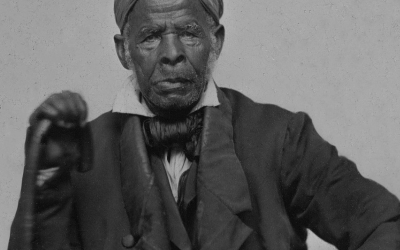

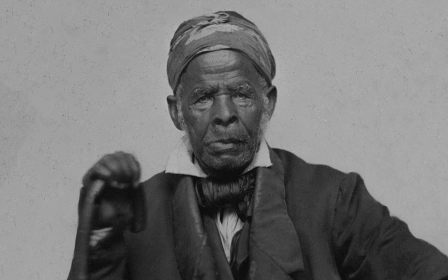

Charleston, South Carolina, was one such port, with over 100,000 West Africans being shipped there. On one of those ships was Omar Ibn Said, a 37-year-old Islamic scholar of Fulani descent.

His story is less well-known than that of abolitionists and former slaves, such as Olaudah Equiano and Frederick Douglass. However, a new opera attempts to rectify this and bring his narrative to light.

Named Omar, it follows Ibn Said's spiritual journey from Futa Toro, a desert region between present-day Mauritania and Senegal, through his enslavement in North Carolina under a man called ‘Johnson’ and later by General James Owen of Bladen county.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Ibn Said died in 1864, one year before the end of the American Civil War that led to the abolition of chattel slavery. He was buried at the Owen plantation, and never gained his freedom.

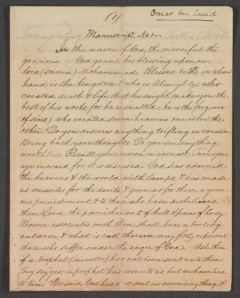

The production is based on Ibn Said's autobiography, which was written in 1831 under General Owen’s instruction.

In it, Ibn Said talks about his life in West Africa, his enslavement, he carefully critiques chattel slavery and touches on the ‘kinder’ treatment he experienced under Owen when compared to his former slave owner.

Owen, who does not “beat” Ibn Said or call him “bad names”, excused Omar from manual labour on the plantation.

Ibn Said’s writings were not edited by Owen - as was the custom for other slave narratives - and so it is therefore regarded as a more authentic account. It is also considered the only surviving autobiography of an enslaved person in the United States written in Arabic.

Omar is one of two opera productions to premiere at the Spoleto Festival USA in Charleston, South Carolina, alongside Karim Sulayman’s Unholy Wars.

The festival’s general director Mena Mark Hanna says Omar serves as a “reclamation of history.”

“It’s a story of the foundation of this country and one that platforms the marginalised at centre stage,” he said. “For these reasons, it’s all the more important that it receives its world premiere here in Charleston, a city that served as one of the main harbours of the Transatlantic slave trade.”

Produced mostly in English, with songs in Arabic and West African languages, Omar’s director, Kaneza Schaal, told Middle East Eye that language was a key aspect of the eponymous character’s life.

"The ferocious clarity of the power of language was such that one of the most sacrosanct laws was that you could not teach a slave to read and write,” Schaal said.

“And here you have this text of Omar, he was literate and wrote in Maghrebi Arabic. Even if it was generated under duress, it is holy. So, I am interested in the contest of languages of Omar’s life, the spiritual, the cultural, the spoken, the written, so we can enjoy his journey.”

As an enslaved intellectual

While Ibn Said's intellect is impressive, it is far from unique. According to historian Sylviane A. Diouf in American Slaves Who Were Readers and Writers, Islam had been present in West Africa for 500 years by the time the Transatlantic slave trade began in 1501, providing the backdrop for a flourishing intellectual culture.

Many continental African Muslim students went on to become theologians, magistrates, scribes, and lawyers in places like Senegal's Kokki and Pire, Mali's Timbuktu, and Djenne, the Ivory Coast's Kong, and Ghana's Bouna.

Baron Roger, a French nobleman who was governor of Senegal, said in 1828 that "there are villages in which we find more Negroes who can read and write the Arabic, which for them is a dead and scholarly language, than we would find peasants in our French countryside who can read and write French.”

On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, the literacy of such enslaved Muslims set them apart from their enslaved non-Muslim peers; US-born slaves were mostly illiterate because it was illegal for them to read and write.

Composer Michael Abels, who co-produced the score for Omar alongside Rhiannon Giddens, said that Ibn Said’s intellectual gifts marked him out from fellow slaves.

“Omar had two masters, one of them was concerned with his physical enslavement (Johnson), the other (James Owen) was concerned with his intellectual enslavement or spiritual colonisation,” said Abels, whose previous credits include scoring Jordan Peele’s 2017 film Get Out.

“Omar was not made to do hard labour,” he added. “Omar’s writings are fascinating for historians to analyse because he is doing what he needs to do in a world that is not friendly.”

As an enslaved Muslim

There are two aspects of Ibn Said’s enslavement that are important because of the period in which he lived.

One was being a slave during a time of increasing abolitionist sentiment, and the second was being a Muslim during a time of increasing Christian evangelical fervour.

His experiences provide an interesting perspective on life for enslaved African Muslims and shed light on the disappearance of Islam among African-Americans during the slavery period until its reemergence in the 20th century.

Historians say that up to 30 percent of enslaved Africans who arrived in the colonies, and subsequently the United States, were Muslim.

“As a scholar of Muslim communities in the West, I know African slaves were forced to abandon their Islamic faith and practices by their owners, both to separate them from their culture and religious roots and also to 'civilise' them to Christianity,” wrote historian Saeed Ahmed Khan in a 2019 article.

Indeed, Ibn Said’s autobiography seems to allude to the possibility that he converted to Christianity.

"When I was a Mohammedan I prayed thus . . . But now I pray 'Our Father,' etc., in the words of our Lord Jesus the Messiah,” he writes in one passage.

Nevertheless, a subtle antipathy towards his Christian slaveholders runs throughout the text and contemporary reports about his life.

University of North Carolina historian Patrick E. Horn cites one 1825 article about Said, which appears in The Christian Advocate.

After receiving a Bible translated into Arabic, it is reported that Said "now reads the scriptures in his native language, and blesses Him who causes good to come out of evil by making him a slave".

Said's autobiography stops short of explicitly professing faith in a Christian God or explaining the reason for his conversion. Instead, he limits his comments to the linguistic distinctions between his old and new prayers.

Consequently, the sincerity of any conversion to Christianity under slavery remains a subject of doubt for those interested in Ibn Said’s life.

The Muslim musical

Omar is not the only musical or opera to delve into the lives of historic Muslim personalities.

Last year, the life of 13th-century Sufi mystic, Jalal ad-Din Rumi, was the subject of Rumi: The Musical.

Its creators delved into the poet’s personal life, including his relationship with his friend and mentor Shams Tabrizi, and produced a score, which combined both Middle Eastern instrumentals and classical European influences.

Rumi’s own poetry helped inspire sets within the musical, touching upon themes of love, gender equality, and the price of fame on personal relationships.

Its release comes amid a separate trend, which Abels calls a “Black opera renaissance”, marked most notably by the 2021 showing of the first production by a Black writer to play at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House in more than a century, Fire Shut Up in My Bones.

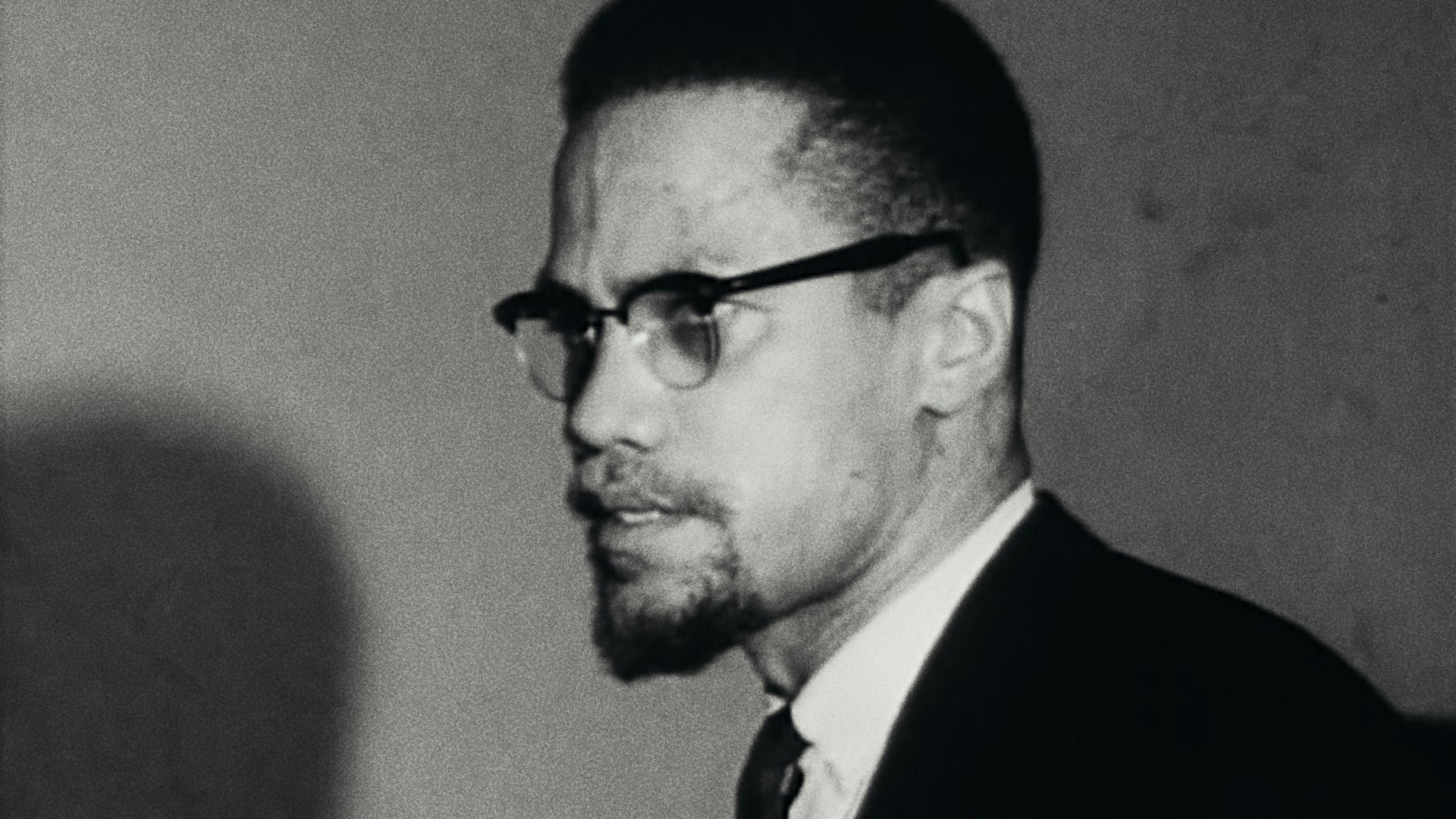

Alongside Omar at the intersection of Black and Muslim-inspired productions, is a planned Autumn 2023 musical based on the life and legacy of the Muslim and pan-African nationalist, Malcolm X.

First reported by the New York Times, the opera will be a reversion of Anthony Davis’s X which premiered in 1985 and played at the New York City Opera in 1986. The newer version, also produced by Davis, will play at the Metropolitan Opera House and will become the second work by a Black composer to appear at the institution.

The focus on Ibn Said, Malcolm X, and Rumi reflects an increasing interest in history to address the spiritual and moral yearnings of modern societies. In the case of Ibn Said, in particular, the renewed interest in his life perhaps exposes a fresh and uncomfortable detail about the enslavement of Africans.

Long seen justifiably as a horror rooted in racism, there was also a religious dimension to slavery evidenced by the pressure on the enslaved to accept the religion of the slaveholder.

Opera is well suited to portray such nuances, say Omar’s producers.

“The West has a fancy of its singularity, it imagines itself as consistent and fixed, and the opera lost itself to that lie, but we know that forms like opera have roots in all cultural exchanges and migrations over hundreds of years,” says Schaal.

“What excites me about Omar is an opportunity to return opera to itself. Opera is big enough for Said’s journey - for the contradictions, the violence, the holiness, the multiplicity, and terror.”

Following its world premiere in Charleston on 27 May, Omar is scheduled to play at LA Opera, Boston Lyric Opera, San Francisco Opera, and Lyric Opera of Chicago.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.