Uzbek embroidery: Meet the women reviving the craft of suzani

As she begins to embroider flowers inside a vine leaf border, Uzbek artisan Mukhabbat Kuchkarova pulls the naturally dyed green silk thread through the cotton sheet.

“I go to another world when I sew,” says the 55-year-old, pointing to a floral design she inherited from her grandmother. “I focus my attention on the petals of the flower, and I think of its beauty.”

Female Uzbek artisans like Kuchkarova are keeping alive a centuries-old technique in a country that has only recently opened its borders to international tourists.

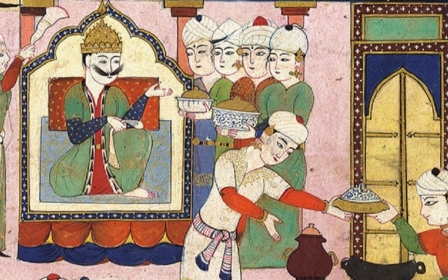

Suzani, which takes its name from the Persian word for needle (suzan), was among many embroidery styles that spread from the silk houses of Central Asia, built during the age of the ancient Silk Road - the 4,000-mile trading route that connected China with Europe until the 15th century

Once sewn only by hand, Uzbekistan’s traditional embroideries had been in decline for the past century.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The slump began during the years of Soviet rule from the 1920s onwards, as Uzbek industry was mechanised and mass production methods were adopted for embroidery.

Rule from Moscow ended in 1991, only to be replaced by that of dictator Islam Karimov, who closed the country off to most foreign travellers.

But visa entry was relaxed a year after his death in 2016 to encourage tourism and economic growth - and with it has come the revival of traditional crafts.

Traditional styles

Suzani was once embroidered only on the furnishings and wall hangings of a bride’s wedding dowry.

Now it has become an economic lifeline for Uzbek women like Kuchkarova, a former government accountant, who left her job after she gave birth to her five daughters.

Her family home is in Talija, a village near Shofirkon city, 50km north of Bukhara. There, Kuchkarova has been running an embroidery business for more than 25 years, an Aladdin’s cave of suzani ornamented with natural motifs including pomegranate, a symbol of fertility; almonds, which symbolise long life; and pepper vines, to ward off the evil eye known as nazar.

Widowed three years ago, Kuchkarova now runs a shop and sells suzani via Instagram and Etsy - mostly to international customers - with help from her daughters.

“For 50 years or so, Uzbek women didn’t sew for themselves,” says Kuchkarova. “Then tourists came to our country. They were interested in our suzani, and they started to buy handmade embroidery.”

Like the country’s non flatbreads, which are identified with unique stamps according to their town or city of origin, Uzbekistan has several centuries-old traditional embroidery styles and variations of clothing.

Doppi hats, for instance, are embroidered with symbolic designs, and stacked in bazaars across the country.

Artist Kamila Erkaboyeva, a colleague to the ambassador of tourism for Uzbekistan in the UK, explains: “Doppis used to indicate social status, marriage status and the region you’re from, based on the colours and the design of the doppi hat. It was a lot like Tinder for my ancestors.”

In the caravan city of Bukhara, a major commercial hub where goods and culture were exchanged by merchants and travellers, pure gold embroidery - known as zardozi - was used to embellish the sweeping chappan robes of the emir and his court when Bukhara became an emirate in 1785.

When the emirate was eventually defeated by Russian imperial forces in 1920, and Bukhara’s final emir - Mohammad Alim Khan - sought refuge in Afghanistan, Bukhara’s zardozi embroidery almost vanished.

But the craft, once taught only to men, is now being preserved by female artisans.

At a zardozi factory in Bukhara city, seven retired female artisans needle away at hand-embroidered pieces of zardozi like a hive of worker bees subdued by smoke.

Sipping at tea, a chitter-chatter of Uzbek rises and falls as thimble thumbs and forefingers thread gold metal thread in and out of rich velvet canvases.

The designs include a replica of the hizam, the gold Arabic inscription that threads its way around the uppermost part of the Kaaba, the holiest site in Islam; and silver leaves interspersing the edges of a lime velvet canvas.

These regal designs, cut by modern lasers but then threaded by hand, can now be ordered by anyone.

“I’m proud of what I’m doing,” says Munira, who began learning zardozi from a master at the age of 16 in 1968.

Tradition battles modernity

For more than 1,500 years, the Silk Road was a cultural conveyor belt of religion, language, philosophy, culture and precious commodities - most notably Chinese silk.

But contact with Europe was lost after the Ottoman Empire closed off trade with the West in 1453.

Today, Uzbekistan remains the world’s third largest producer of silk after China and India, and the revival is booming thanks to the work of largely female artisans.

In October 2023, Bukhara was added to the Unesco Creative Cities Network of almost 300 cities globally, which identifies cities prioritising creativity and cultural industries as part of their development plans.

I am very proud that Bukhara has been added to the prestigious UNESCO Creative Cities Network. It is remarkable that the historical and cultural heritage of this ancient city has received a worthy assessment from the world community.

— Saida Mirziyoyeva (@SMirziyoyeva) November 1, 2023

⠀

In 2025, Uzbekistan Art and Culture… pic.twitter.com/lYlBhszhfB

Beyond Uzbekistan, the threads of its embroidery have been embraced by a diaspora keen to reconnect with their identity and heritage.

In London, Erkaboyeva, who lived in Uzbekistan until she was 11, launched her own Uzbek-influenced artisanal business Arty Numpty.

She was inspired after watching “The Doppi Project”, a YouTube documentary by British filmmaker Nadir Nahdi, which follows an Uzbek-Uyghur woman’s search for a traditional doppa hat.

The video also looked at Uzbek embroidery and silk textiles manufactured in the Fergana Valley, the birthplace of Erkaboyeva’s father.

“I once had an argument with a friend, an Uzbek native, who was born and raised in Uzbekistan in regards to the craftsmanship on the traditional doppis and suzanis. A friend insisted on buying a cheap, fabricated and mass manufactured suzani and doppa at the bazaar rather than from a local craftswoman simply because it’s easier and the fraction of the price doesn’t justify the product,” Erkaboyeva said.

“It led me to realise that there is a misconception and disconnection between the craftsmanship, the process, and my generation.

“For instance, suzani used to be considered to be as precious as gold in each Uzbek household. One generation starts the stitch, another finishes. The suzani is passed on from a grandmother to start, mother to continue and daughter to finish,” she added.

“What is passed on through a thread is more than just the beauty of the fabric.”

The town of Margilan, nestled in the Fergana Valley and six and a half hours by train east of the capital Tashkent, has been a major producer of Uzbek silk for around 1,500 years.

'What is passed on through a thread is more than just the beauty of the fabric'

- Kamila Erkaboyeva, founder Arty Numpty

Every year from the end of April to late May, silk weavers painstakingly harvest moonlight-coloured silk threads, one at a time, from silk cocoons spun by silkworms that have feasted on mulberry tree leaves during the spring.

Established in 1972, the factory, previously a mosque, is renowned for its vivid hand-dyed Khan-atlas royal silk, and adras and ikat textiles, all of which begin with a single thread of raw silk.

Weaver Aina Khan, 66, who learned the trade from her father, explains: “It was the men who used to work in this factory.”

As time passed, the men took on the more laborious task of producing natural dyes from dried pomegranate husks, saffron, onion skin and acacia flowers, and other ingredients.

But now cheap, mass-produced silk from China has eroded Uzbekistan’s silk market, according to Khan, who started work at the factory in 1983 after the birth of her twins.

“In those days, the cocoons were larger,” says Khan, as dozens of white silk cocoons pop inside a boiling vat and she deftly scoops a handful of web-like filaments slowly unravelled by a spinning wheel into a sturdy spindle of raw silk.

“The Russian caterpillar ate more mulberry leaves. Nowadays, we have Chinese cocoons which are smaller.”

Back in Bukhara, Kuchkarova employs some 500 Uzbek women and young girls to produce suzani textiles using only naturally dyed raw silk threads.

In a country of 36m, where 17 percent of Uzbeks live below the poverty line, it is no surprise that some businesses and consumers are turning to cheaper, machine-embroidered designs and fluorescent-coloured artificial dyes.

“But not us,” says Aziza Tojiyeva, 24, the youngest of Kuchkarova’s daughters. Pointing to a small pillowcase with a floral motif, she explains how the art of suzani “requires so much patience. We need 15 days for one person to complete it.”

Meanwhile Kuchkarova watches her granddaughter, Gulasal, assemble a petal one stitch at a time with lightning speed. The 11-year-old is part of the fifth generation of suzani embroiderers in her family.

“I was 13 years old when I first watched my grandmother sew suzani on a napkin, and tried it myself,” says Kuchkarova. “My granddaughter sews suzani just as I did.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.