Uzbekistan: Fabled non flatbread endures along the old Silk Road

With a torch strapped to his head to pierce the darkness of his bakery, Hasanboy Karimov, from Uzbekistan’s eastern city of Margilan, swoops gracefully into a blazing tandoor.

With a firm smack of his right hand, 57-year-old Karimov, a "nonvoy" or "non" flatbread baker, sticks a swirl of raw dough into a domed clay ceiling encrusted with nons browning under the excruciating heat.

An immaculately round flatbread usually made of white flour, water, salt and yeast, non is a Persian word and a cognate of the “naan” found in South Asia.

A staple of Uzbek culture for centuries, although non is also prepared in a tandoor (or tanoor), it is nevertheless distinct from “naan” found in India and Pakistan.

What distinguishes Uzbek non from those of its neighbours in nearby Afghanistan and Tajikistan are its many regional variations.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"Each region is famous for its own distinct flatbreads and each one has their own lovers," says Bahriddin Chustiy, one of Uzbekistan’s most prominent chefs and author of several cookbooks including one simply titled “Non”.

"As they say, taste and colour have no comrade," Chustiy adds, citing a Russian proverb.

Marked in the middle with a chekich, a stamp made of walnut wood with steel needles forming decorative shapes that prevent the flatbread from rising, each region of Uzbekistan has its own signature for non.

What unites these many variations is an underlying culinary philosophy rooted in the country's ancient past.

“The process of making non emulates the warmth and energy of the sun. Both non and the sun are sources of energy in our culture,” says 45-year-old Sanober Majidova, who runs Samarkand Palav, an Uzbek food pop-up that runs once a week in London.

For thousands of years, wheat, a staple ingredient used to make non, was religiously significant in Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest known living religions, which first took root in Central Asia.

“[Non’s] round shape harks back to the significance of the sun in Mithraism, where Mithra was the Iranian god of the sun,” says Majidova.

For many Uzbeks, non is the foundation of Uzbek cuisine and day-to-day life.

On trains and planes, Uzbeks can be seen cautiously stowing stacks of tenderly wrapped non in overhead compartments meant for luggage. The flatbread is a communal food meant to be torn by hand and shared.

“At weddings, the bride and groom both take a bite of a non at the ceremony, and then finish it the next day as part of their first meal as man and wife,” says Caroline Eden, who spent a decade in the region and is the author of two books on Central Asia, Samarkand and Red Sands. “If a soldier goes off to war, he takes a bite of non as he departs, and his family will hang the bread up and only take it down once he is safely home.”

'An emblem'

Under the azure carapace of the capital Tashkent’s Chorsu bazaar, the largest market in the country’s capital, a group of Russians marvel at rows of light and crispy Tashkent non.

Since the start of Russia’s military campaign in Ukraine, tens of thousands of Russians have fled to former Soviet republics in Central Asia to evade conscription, including Uzbekistan where Soviet rule collapsed in 1991 after eight decades.

“Shukhrat Abbasov, the father of Uzbek cinema, used bread as an emblem for Tashkent's ability to shelter the needy in his popular 1968 film, Tashkent: City of Bread,” says Eden.

Under Soviet-Russian rule, the Central Asian states were essentially bread baskets for the empire. Today, Tashkent’s non has the potential to feed their neighbours to the north, but on more equitable terms.

Traditional non making practices have also changed.

For decades, Uzbekistan was largely closed off to most foreign travellers until the death of the country’s first post-Soviet president and veteran dictator, Islam Karimov, in 2016.

To entice tourists amid a political and economic overhaul called the Uzbek Spring, visa liberalisation in 2017 allowed travellers from dozens of countries to enter Uzbekistan without a visa for up to 30 days.

Tashkent, the country’s capital, has a booming restaurant culture of modern restaurants and hipster coffee shops, one named after the Muslim philosopher, Ibn Sina or Avicenna. Matriarchs of Uzbek families are no longer the sole bakers of non. But it remains ubiquitous, albeit with new traditions.

Bahriddin Chustiy was 10 years old when he cooked his first non at a local bakery in his home-town of Chust in the north of the Ferghana Valley. "On weekends and during vacations, I occasionally went to this bakery and helped,” says Chustiy, 39. “I laid out the finished nons, spread milk on the flatbreads, sprinkled sesame seeds and other small jobs that a 10-year-old boy could do."

"Because we have our own restaurants and bakeries, the flatbreads are prepared mainly by professional bakers," he adds.

According to Eden: “Traditionally, non bread was never cut with a knife and was always torn by hand by the head of the table, though this is becoming less common now, especially in restaurants. She adds that as more people travel to Uzbekistan, lighter breads such as the Armenian lavash bread or Turkish flatbreads are being served.

“One other tradition that has almost disappeared is the use of a traditional parak, an old-school bread-stamping tool made of 50 or so sharp-tipped rooster feather quill,” Eden says.

With one foot still submerged in its Soviet past, the pressure to mechanise from Moscow which resulted in Russian sandwich-style loaves that were never consumed with the same fervour as non, has been eclipsed by the ovens of modernity.

“In the past, our people used sourdough, unbleached organic flour, and firewood for baking. Nowadays, it’s more common to use baking powder, white flour, and ovens, affecting the texture of the bread,” says Majidova.

That said, some traditions associated with non remain firmly rooted. The division of labour when it comes to non culture, for instance, is generally split according to genders, with the more laborious tasks being designated to men.

While elderly women or “babuskhas” sell their wares on streets and markets early in the morning, young men transport fresh non on crates balanced precariously on the rear of their bikes, and men like Karimov take on the laborious and somewhat precarious work as nonvoys.

For more than three decades, Karimov has baked Margilan’s non flatbreads, a trade he learnt from his brother.

In summer when temperatures soar to over 45 degrees, Karimov continues to bake.

“If I don’t work hard, I won’t be able to earn,” he says. Karimov has miraculously never sustained a serious burn swooping in and out of the tandoor. “God saves me every time!” he adds.

Variations

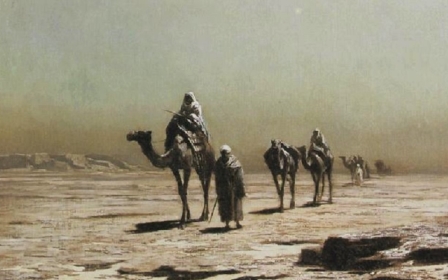

Each city in Uzbekistan has its own variation of non. In the ancient city of Bukhara, situated along the 4,000-mile-long Silk Road trading route that connected China and Europe, non bears a flower-shaped stamp in the centre.

“Samarkand non, which looks like Iranian non, is said to be the best,” Karimov says diplomatically, not revealing what his own palette leans towards.

The southeastern city of Samarkand is legendary for its doughy, chewy non with a smooth golden crust, weighing around one and a half a kilos.

'Arab people called Margilan the city of meat and non'

- Hasanboy Karimov, nonvoy

Among Samarkand’s flatbread admirers was the 14th century emperor, Timur, known in the West as Tamerlane.

On one of his many bloody campaigns, Eden recounts, Tamerlane is said to have killed a group of bakers from Samarkand he had brought with him on his travels, after they failed to replicate the fabled Samarkand non.

Since then, non folklore concluded that the air of Samarkand is what gives its non an inimitable flavour.

Despite Samarkand’s reputation as the country’s non capital, regional non pride is a fact of life for Uzbeks. “Samarkand non is a bit sour,” says Shahzad, a silk factory employee from Margilan. “It has got a lot of salt.”

Located in Fergana valley where the founder of the Mughal dynasty, Babur, was born in the 15th century, Margilan is the centre of silk production in the country.

“Arab people called Margilan the city of meat and non,” Karimov says, referring to Arab chronicles of the city dating back to the 10th century.

Its non boasts a unique flower-shaped patir. It also has a traditional round variation with sesame seeds encrusting the rim, and a dash of kalonji seeds in its centre.

“Margilan’s non is best,” Shahzad says, his bias beaming through the gloriously brown non in his hands, still steaming from the tandoor.

Holding a freshly baked Margilan non, it is clear there is something almost sacred about this humble flatbread. “Take one,” Karimov says jubilantly. Non is, after all, something to be shared.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.