Visa denied: Sudanese author’s literary journey blocked by UK Home Office

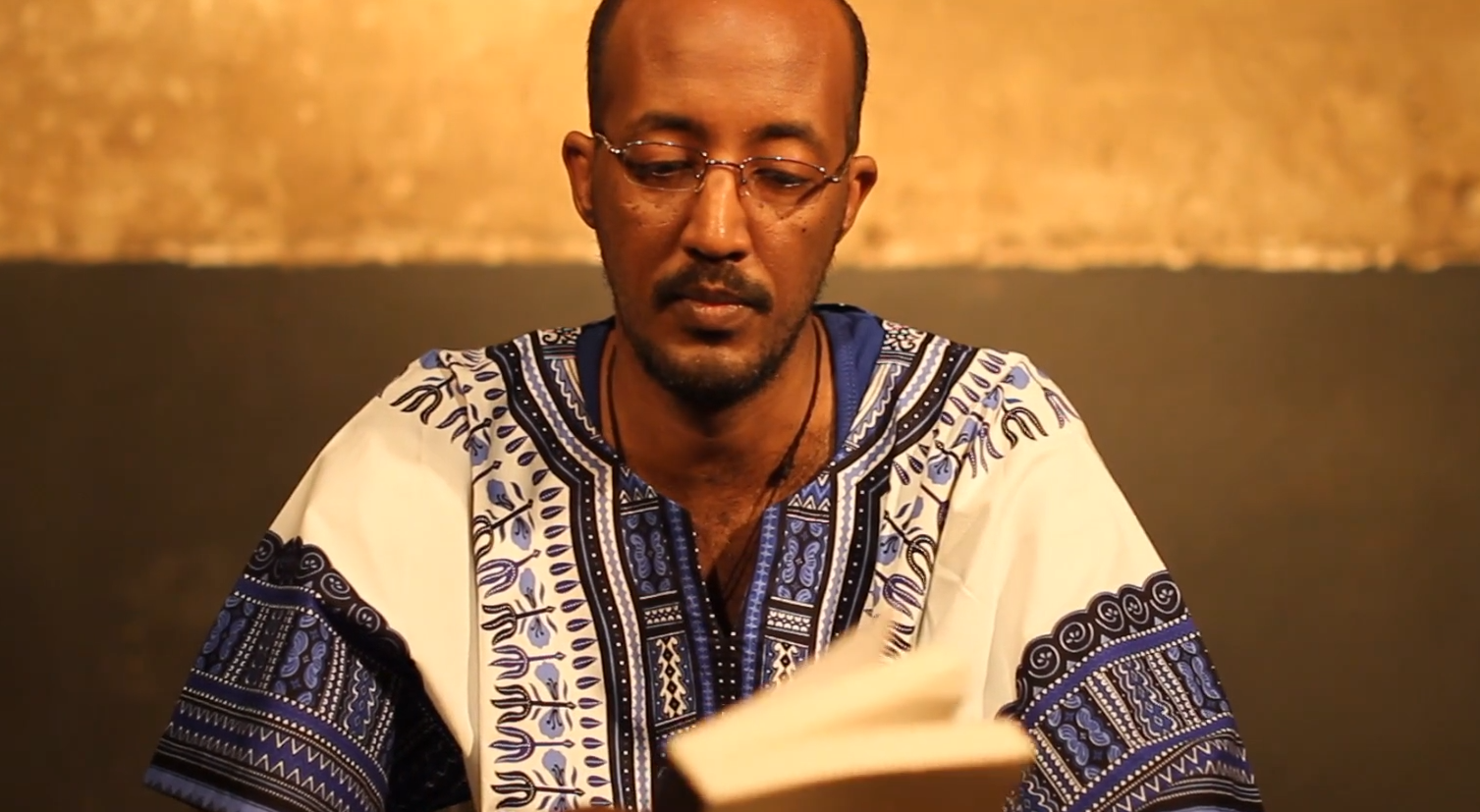

Hammour Ziada, an award-winning Sudanese writer, was due to come to Durham University as a guest of its faculty for a fellowship programme.

Instead, the UK Home Office refused him a short-term visa.

'I have always dreamed of seeing the archive on Sudan at the University of Durham'

- Hammour Ziada

The author had been officially invited as the 2019 Fellow of the Banipal Visiting Writer Fellowship, an initiative set up by St Aidan’s College of the University of Durham and Banipal Magazine of Modern Arab Literature, with the support of the British Council. Banipal Magazine is a well-known name in the field of Arabic literature in translation.

As well as an award-winning author, Ziada is a journalist and left-wing activist of Sudanese origin now living with his family in Cairo. He moved to Egypt at the end of 2009 after his house in Sudan was set on fire as the political situation in Sudan worsened.

He explains to Middle East Eye from Cairo that his house was attacked because of an article he wrote against a radical Islamic group. "The leader of the group wrote a fatwa that communists are not Muslims.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"Around the same time I was accused of publishing a story… that encouraged people to [commit acts considered] haram," he explains, using the term for acts forbidden by Islam.

Ziada was declared an infidel. His safety threatened, he left Sudan for Cairo, where his writing career blossomed.

Accolades and love of country

Ziada received the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 2014 and was short-listed at the 2015 International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF), and his work has been translated and published into English and French.

His published works of fiction include A Life Story from Omdurman (short stories, 2008), Al-Kunj (a novel, 2010), Sleeping at the Foot of the Mountain (short stories, 2014) and The Longing of the Dervish (a novel, 2014).

Ziada has declared his disapproval of the Sudanese political leadership and in 2015, he said he writes about his country not just for the sake of storytelling, but also “for my deep longing for the country, which I hope to return to one day”.

Denied entry

When Middle East Eye requested comment on Ziada’s visa case, a Home Office spokesperson responded: “All cases are decided on their individual merits, on the basis of the evidence available and in line with UK immigration rules.”

The Fellowship was told the Home Office was not satisfied that the author is “genuinely seeking entry as a visitor or intends to leave the UK at the end of [his] visit”.

Ziada says he believes his culture should be known to the rest of the world and, as he explained to Middle East Eye, expected to further this goal with his fellowship at St Aidan’s.

“I have always dreamed of seeing the archive on Sudan at the University of Durham. I also have a historical narrative project that takes place in some parts of Britain.

“I was very interested in seeing the places I want to write about.”

Sadly, this is not possible, but the author has found a way of resisting: “The rejection did not hurt me on the economic level,” he commented, “but it certainly spoiled some of my literary plans. But I will not make the position of the visa issuer destroy what I intend to write.”

No bridges to Sudan

The visa refusal also came as a shock to the Banipal Visiting Writer Fellowship. Now running for its third year, the grant was previously awarded to Arab authors who were already EU residents. This was the first time, from its inception in 2016, that the fellowship was offered to a writer living outside the EU.

'Hopefully, we will welcome Mr Ziada at Durham University in 2020'

- Fadia Faqir, Writing Fellow

“The Fellowship’s purpose,” Banipal explains, “is to encourage dialogue between the UK and the Arab world through literature.”

“Part of St Aidan’s College ethos,” said Writing Fellow Fadia Faqir, “is building bridges between cultures, countries, and communities. The Banipal Visiting Writer Fellowship is an integral part of our project.”

She said the issue of Ziada would not stop the programme from continuing. “Not giving Hammour Ziada a UK visa is a setback, but we are determined to continue creating dialogues between civilisations wherever and whenever we can. Hopefully, we will welcome Mr Ziada at Durham University in 2020.”

St Aidan’s college and Banipal co-signed a letter, published on the Facebook page of the Banipal Visiting Writer Fellowship, where they explained that this decision was a massive obstruction for them and could “jeopardise the future of the Fellowship”.

Outrage and shock

Margaret Obank, publisher of Banipal Magazine and a Fellowship trustee, said: “We were devastated and shocked that such a talented author as Hammour Ziada could be refused his visa, so are holding the Fellowship open for him to take up next year, and in the meantime working to challenge the illogical and unjust decision.”

She added: “I am at a complete loss to understand how his application could have been rejected.”

Ziada’s visa refusal comes less than a year after the UK-Sudan Strategic Dialogue meeting, held in Khartoum in April 2018, in which the two governments declared their commitment to cultural and educational exchange between the two countries.

The statement from the meeting read: “Both sides were pleased with progress to deliver the current celebrations of the 70th Anniversary of the British Council in Sudan and agreed to continue exchanges on cultural and educational issues, including primary and higher education, digitisation of archives and co-operation on youth strategies.”

But whilst travel impediments are nothing new to artists coming from the Arab World, the negative stance towards cultural exchange from the Home Office has caused an uproar in the arts community, according to dozens of UK arts festival organisers who wrote to the Guardian last summer.

Hostile environment

“The UK has a rich history of hosting the best artists from across the world, and these refusals directly reduce UK audiences’ opportunities to see and engage with international artists. We request that the UK government considers these changes to ensure the free flow of arts and ideas into the country,” they wrote.

The “hostile environment” applied to former Commonwealth citizens has caused a scandal for the Home Office over the last year, but for artists and writers coming to the UK, it seems the policy of suspicion is still very much in place.

'I am a Sudanese citizen and I want to stay in the Middle East, in an Arab country because I have something to do here'

- Hammour Ziada

Banipal publisher Obank expressed the anger of many in the academic community when she says: “The continuing hostile environment towards international visitors is a source of utter frustration and shame as well as outrage.

“The mounting number of refusals of visas to bona fide authors, speakers, researchers, and scientific, cultural and literary figures, invited to the UK for specific purposes and short visits, is looking like a list of distinguished guests rather than as they are portrayed by the visa office.”

Thinking back to his decision to move to Egypt, rather than apply for asylum in the West ten years ago, Ziada has no regrets. He refutes the Home Office claims about his reasons for coming to the UK.

“If I wanted to have asylum and be a refugee in the West I had a case. I could have done it ten years ago. I don’t want to do that. I am a Sudanese citizen and I want to stay in the Middle East, in an Arab country because I have something to do here.

"I have a project, I am a writer, I have my audience here, the publishers are here. I can’t imagine my life out of these Arabic speaking countries. Living in Egypt makes me feel [at] home.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.