The two faces of western cinema: Righteous anger on Ukraine, silence on the Middle East

In September 2019, Egypt was rocked by the biggest wave of mass protests since incumbent President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi took office in 2014.

Around 4,300 civilians were arrested during the unrest, according to a European Parliament resolution on Egypt.

Citizens, including teenagers and Coptic Christians, were randomly stopped in the streets by plain-clothed officers, had their phones vetted for anti-state material and detained.

At the same time, Egypt’s Gouna Film Fest in the beach resort of Hurghada was nonchalantly rolling out its red carpet for its closing ceremony.

A privately funded luxury festival designed to promote the artificially constructed resort, the event has garnered enormous media attention regionally since it started in 2017, drawing top film industry names from around the globe.

With the dismantling of the Dubai and Abu Dhabi film festivals, Gouna was a chance for film executives to discover regional talents while enjoying a free vacation by the Red Sea.

Politics was clearly not a concern for most of the international guests, who turned a blind eye to Egypt’s abysmal record on human rights and freedom of speech.

By then, Egypt’s reputation as a brutal authoritarian regime was no secret, yet that did not seem to trouble the western filmmakers descending on Gouna to scrutinise an indie scene devastated by state censorship.

Their silence at the festival’s tone-deaf closing was nothing short of disgraceful.

That same evening, the fest's billionaire founder Naguib Sawiris took aim at the Hollywood stars who had turned down invitations for buying into “malicious reports” about Egypt’s security situation.

“You can’t cave in to the fear of terrorism,” he said as people were detained across the country.

The 2019 protests made headlines globally but even after returning home, the western guests – producers, film journalists and others- chose not to speak on the subject.

Many returned to Gouna for future iterations of the festival; those who did not had reasons other than politics.

Double standards

Taking shelter at home from the bedlam that ruled Cairo that weekend, for this author, the Gouna closing felt like an empty spectacle ironically celebrating films that tackled an Arab reality that the festival itself was disconnected and detached from.

I didn’t just feel abandoned by my own community; I was disillusioned with the entire listless enterprise.

I couldn’t help but recall the episode, which went unreported by the foreign film press, amid calls to boycott films funded by the Russian state in the aftermath of the invasion of Ukraine, calls that have resonated strongly within European and American film communities.

Western cinema’s stance against Russia has been resolute from the get-go.

'One cannot help but see the hypocrisy in Western cinema's reaction to the conflict in Ukraine'

Top studios, including Disney, Warner Bros, Universal, Sony Pictures and Paramount, have suspended film releases in the country. Netflix stopped streaming in March and the European Film Academy excluded Russian films from its prizes after deducing that all Russian films are state-funded.

Western film festivals have followed suit: Vilnius, Glasgow and Cleveland have all dropped Russian titles from their lineups, while top festivals, such Cannes, Venice and Berlin, among others have stated they will not accept films associated with the state or Putin.

The stance is far from trivial or symbolic. Russia is a global cinema powerhouse and an important film market. Cultural pressure is an important tool in countering Putin’s authoritarian expansionism. This is an imperative ethical standpoint western cinema is expected to abide by – a standpoint that defines what artists and curators regard as the beating heart of art.

Yet, observing this wave of righteous support with a Middle Eastern eye, one cannot help but see the hypocrisy in western cinema's reaction to the conflict in Ukraine in contrast to its indifference to human rights abuses in the rest of the world.

Time and time again, the film industry has turned a blind eye to thorny politics in the Middle East, and time and time again western cinema has used its geographical and cultural distance from the region to justify its ignorance towards it.

And like the 2019 Gouna delegates, who chose to remain silent as a nation loses another fight for democracy, western cinema has proven its double standards when dealing with cultural enterprises outside of its borders.

Over the past decade, I have heard every argument imaginable from journalists and programmers working with authoritarian regimes, such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

“If we boycott one country on the basis of its human rights abuses, we’re not going to go anywhere,” several journalists told me.

“We want to discover new artistic voices from the region; that’s our main objective. Art trumps politics,” programmers have said.

Others meanwhile have been ringing the hollow platitude that “arts and culture should be separated from politics” – a motto not a single western cultural worker can utter again in light of what Russia is doing in Ukraine.

The myth of the apolitical

Art and politics have never and could never be separated – maintaining an apolitical position towards art is in itself a political choice.

Questions of authorship, state funding, and covert political ideologies are contentious issues that are hard to detect and decipher without the help of those who know a region.

The problem is especially pronounced when these issues are not considered to begin with.

Only pro-Assad Syrian films have been unwelcome in western venues; but issues with productions from the rest of the region have been treated with apathy and sloppiness.

It doesn’t matter that feminist filmmakers embrace the ideologies of their governments in their work; it doesn’t matter that prestige pictures are produced by companies run by military intelligence; and it doesn’t matter that an upcoming director is supported by a murderous ruler.

These issues are more complicated for western film industry figures to grasp, or so they say; but are they less morally reprehensible than what is happening in Ukraine?

It is undoubtedly important for the western film industry to nurture and back budding independent filmmakers in the Middle East, but there’s a big difference between constructive support and idle participation in the face-lifting parades set up by authoritarian regimes.

To pretend that festivals are not a tool of soft power used by governments to acquire legitimacy is naive. Local celebrities at every major fair patriotically emphasise the importance of festivals in promoting their respective countries. It is what many of the region’s events were fundamentally designed for.

Given the abuses and wars associated with these authoritarian states, why is participation in such events more acceptable than accepting pro-state Russian films?

State censorship and film festivals

In 2016, Tamer El-Said’s debut feature, In the Last Days of the City, was removed from the lineup at the Cairo Film Festival competition for “violating" the festival’s policies.

It was clear from the get-go that the film – which includes footage of police protests in a pre-2011 revolution Cairo – was pushed out due to censorship, yet the festival directors claimed otherwise at the time.

Condemnation by foreign filmmakers and a boycott by their independent Egyptian counterparts did not stop the festival from continuing as normal the following year with western participants ignoring the blatant censorship.

In 2019, former festival director Magda Wassef finally revealed that an undisclosed “body” instructed the fest to withdraw the film, hiding the real motives for the withdrawal. The revelation never made the news, as is the case with other small films banned from Egypt for political reasons in recent years.

Contrast that episode with what happened at the Antalya Film Festival in 2014. There a similar exclusion of Reyan Tuvi’s Gezi Park protests documentary Love Will Change the Earth sparked a boycott involving 150 filmmakers and critics.

European film industry figures rightfully followed suit, leading to a major shakeup in the festival’s hierarchy and a more transparent approach in dealing with censorship.

That was not the case with Cairo, whose profile was boosted with the arrival of Mohamed Hefzy, the patron of Egyptian indie cinema, who admittedly transformed the festival into a major regional event thanks to solid programming and a robust industry arm.

Censorship never disappeared, however, and the fest continued to struggle in vain for independence from a government that continues to have a tight grip on every aspect of culture.

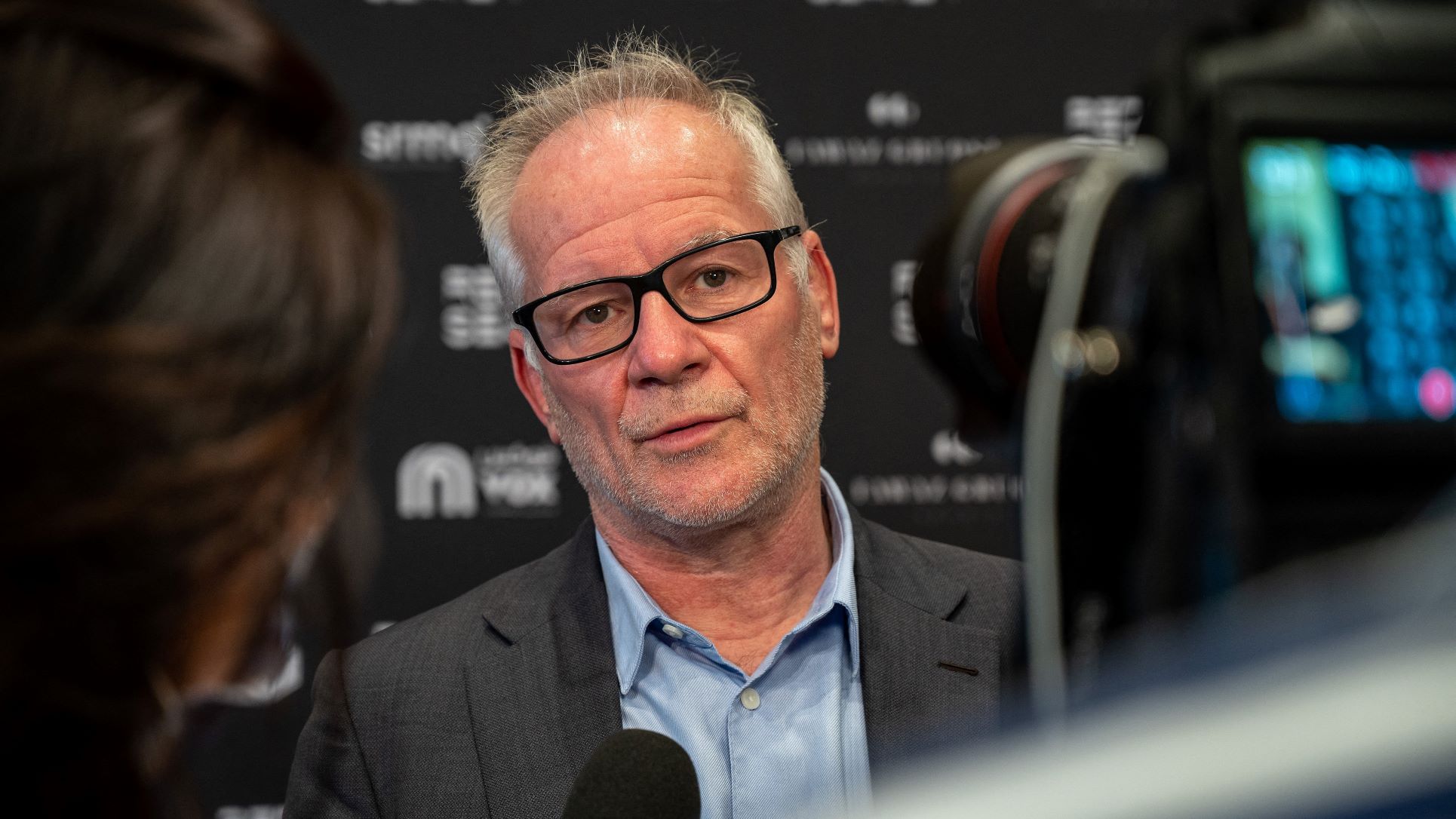

Underlining this dual standard, it was strange to see Thierry Fremaux, the artistic director of Cannes and one of the most powerful figures in the film business, making an official visit to Cairo – where he received the lifetime achievement award – and, more bafflingly, to the inaugural edition of Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Film Festival last December.

The sudden mushrooming of Saudi Arabia’s film market has been the talk of the region lately. An international film festival in a country ruled by a man involved in the murder and persecution of critics was always going to be accused of whitewashing.

With unclear funding and long-term objectives - we still don’t know if aides to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) are involved or have a say in the festival's organisation - a visit to the event could inevitably be seen as an endorsement for the Saudi government’s rebranding efforts.

While some figures in the industry demurely opted to avoid attending, at least till the independence and seriousness of the fest is proven, Fremaux was joined by Hollywood stars such as Clive Owen, Hillary Swank and Vincent Cassel, without much dissent from their peers.

Given that the festival came amid the Saudi war in Yemen, which has killed tens of thousands of Yemeni civilians according to the UN, why is participation considered more permissible than in Russia?

Is Egypt’s gross human rights violations against its own citizens more tolerable than similar abuses in Russia?

What bigger tragedies need to occur for western cinema to start taking the situation in these countries seriously?

Another Giulio Regeni? Another Khashoggi? Another crackdown on the press? More war?

Dissent as a western privilege

The situation in Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Turkey is arguably more clear-cut to judge, for the western eye at least, than the eternally prickly subject of Israel and Palestine. But given Israel’s abuses against Palestinians living under its rule, shouldn’t there be at least an open discussion on the funding and politics of Israeli films?

Speaking out is a western privilege most Middle Eastern film workers do not enjoy. Many of the programmers and organisers in festivals like Cairo or Gouna or Red Sea are passionate, forthright professionals fighting for limited space to express themselves under the watchful eye of their respective governments and risk having their careers terminated if they decide to go against their rulers.

It should be stressed that the demand is not for a total boycott of state-funded and state-sympathetic festivals.

The industry arm of Cairo in particular has flowered into a robust co-production hub in the region, although any politically probing local projects, such as El Said’s new film, understandably find it a perilous terrain. The Red Sea Festival is also lending its young Saudi talents the international exposure they thoroughly need.

Nor is there a call for a total boycott of films from Egypt, Saudi Arabia or Israel. But discarding the issues of funding and politics from this part of the world is as unscrupulous as the blind acceptance of Russian films.

Official representation by the western film industry in state-sponsored and state-sympathetic festivals should also be approached with the same moral seriousness. Several producers, distributors and programmers I spoke to prior to the Red Sea Festival informed me that Fremaux’s presence at the festival encouraged them to toss aside their ethical qualms and join the party.

“We don’t stand on a moral high ground,” several producers told me. “If he’s going, then I guess it’s ok for us to go.”

The presence of Fremaux and other respected figures in the region is undeniably important to Middle Eastern filmmakers, but not in this context or setup.

Official representation of influential and respected figures gives legitimacy to the hosting institutions and their backers, leaving in the dust smaller independent organisations, festivals and initiatives striving for change.

The power to bring about change

The association of major film industry figures with any institution is dictated by personal relations, common benefits, and different power dynamics. Contrary to what we would like to believe, ethical considerations play a minor role in these structures.

Legitimacy should be earned, not bought, but that’s rarely the case in the film world.

But with Russia and Ukraine, western cinema has adopted a lofty moralistic position it now needs to generalise in its relations with the rest of the world, or else stand accused of being two-faced.

Every industry figure from now on must ask themselves this question: is the suffering Sisi or MBS have subjected their people to, or the crimes that Israeli leaders have committed against Palestinians, more morally acceptable than Putin’s? Is it more ethically imperative to vet the profiles of Russian filmmakers but not the Egyptian, Saudis, Turkish or Israeli ones?

The deafening silence of the international film delegates in the 2019 Gouna festival stand in contrast to the unified front of solidarity with Ukraine.

We need a transparent and democratic industry for all; we need to provide havens for critical voices and shun fascistic views; we need to embolden independent spaces and question state-sponsored and state-sympathetic institutions everywhere, with or without participating in them.

Supporting local and regional talents should not come at the expense of legitimising tyranny, and if western cinema desires to be “woke”, it must be woke for all.

The few independent regional reporters have to contend with mounting risks if they criticise the propaganda mechanisms partially informing some regional film events; privileged foreign critics and curators, on the other hand, will go back to their countries unharmed.

Their silence normalises a situation that cannot be normalised, and is a betrayal of a cause artists and activists have sacrificed their lives for.

Last week, one film announced in the official Cannes competition caused a considerable stir: Boy from Heaven by Swedish-Egyptian filmmaker Tarik Saleh.

Described as “a political thriller unfolding in a prestigious religious university in Cairo,” Saleh’s hotly anticipated new creation is the soul cousin of 2017’s global smash hit The Nile Hilton Incident, another political thriller touching upon police corruption in pre-2011 revolution Egypt.

The Cairo production of that film was shut down by the authorities, forcing the production to move to Morocco. Following its release, the film was prohibited from screening in Egypt, with one venue raided by the police for showing the film.

Fremaux casually referred to Boy From Heaven as an Egyptian film despite it having no Egyptian producers, no Egyptian cast and crew, and having been shot outside Egypt.

The film is expected to be banned in Egypt by the same authorities that co-hosted and feted the Cannes chief last November in Cairo.

The moral ambiguity of Saleh’s picture pales in comparison to the film business; a world where moral ambiguity is the modus operandi.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.