How the 1931 World Islamic Congress in Jerusalem made Palestine an international cause

Drawing Muslim thinkers and politicians from across the world, the 1931 World Islamic Congress in Jerusalem was a watershed moment in Islamic politics.

It marked the establishment of the Palestinian struggle as a pan-Arab and pan-Islamic cause, laying the groundwork for the eventual emergence of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation.

The story of how the gathering came about provides a window into a world of largely forgotten international Muslim alliances and political experiments in the interwar period, which operated across imperial and state borders.

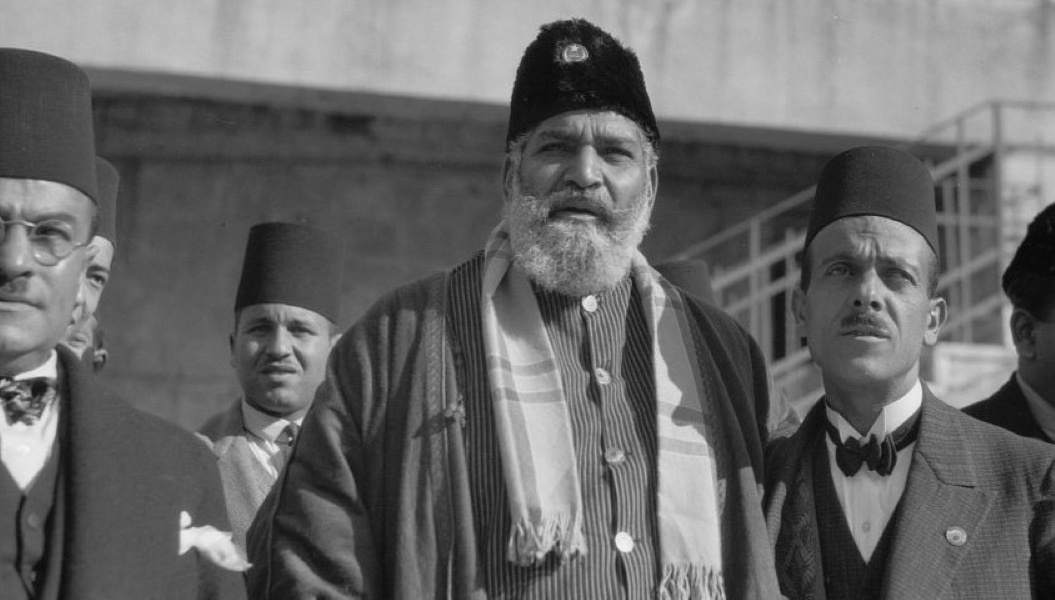

One of its main organisers was Mufti Haj Amin al-Hussaini, then mufti of Jerusalem and a leading opponent of Zionist settlement in the British Mandate of Palestine.

Famous today for his stridently anti-British politics in the late 1930s and 1940s, a period in which he sought alliances with fascist Germany and Italy against the British, Hussaini had previously worked pragmatically under the British Mandate.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

So pragmatically, that in 1929 he agreed to a parliament with proportional representation for Jews and Palestinian Arabs under British authority.

The idea was blocked by Zionist leaders, including future Israeli Prime Minister David Ben Gurion.

Indian Muslims, during their struggle against the British, were another major contingent involved in organising the conference.

As the subcontinent's Muslims sought to carve out their own identity they increasingly attached themselves to global Islamic causes.

A key player in the burgeoning pro-Palestinian movement was the writer Mohammed Ali, who in the early 1920s, participated in Indian politics, negotiated with the British Raj and helped lead the movement to defend the Ottoman caliphate.

Ali also made contact with Hussaini, becoming intensely interested in the Palestinian anti-colonial struggle. He saw it as a cause for Muslims to rally behind, in support of Islamic unity and opposition to European colonialism.

Ali died in London on 4 January 1931 before the event was organised. But his death proved to be pivotal in bringing about the congress later held in Jerusalem.

Upon hearing of Mohammed Ali's death, the mufti sent a telegram to his brother Shaukat, also a significant political figure, requesting that Ali be buried in the precinct of Jerusalem's Al-Aqsa Mosque, the world's third holiest Muslim site.

And so it was that Mohammed Ali’s coffin arrived in Jerusalem on Friday 23 January 1931, to be escorted by a heavily-publicised funeral procession of thousands of Palestinian Muslims to the Dome of the Rock.

The mufti gave a eulogy; so did renowned Egyptian thinker Ahmed Zaki Pasha and Tunisian nationalist Abdelaziz Thaalbi. An Arab Christian poet even read out a poem he had composed in Ali’s honour.

For the mufti, it was an important political moment in establishing Jerusalem as a sort of capital for Islamic politics.

He was naturally delighted when, after the funeral, Shaukat Ali suggested that a conference of Muslim notables from across the world be held in Jerusalem.

A World Islamic Congress was swiftly scheduled for December, almost immediately triggering rumours of a grand plot to restore the Ottoman caliphate.

Restoring the caliphate

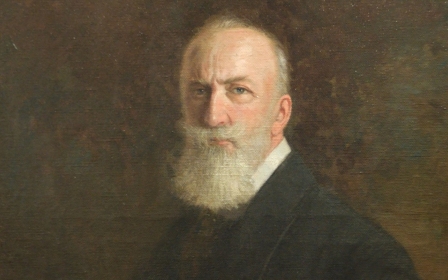

It was certainly Shaukat Ali’s aim: he headed for the French Riviera to meet Abdulmecid II, the former Ottoman caliph, a title which claimed succession to the Prophet Muhammad and leadership of the Islamic world.

After the caliphate was abolished in 1924, the fabulously wealthy nizam of Hyderabad, ruler of India’s largest princely state, supported the former caliph financially, letting him take up residence with his family in a villa on the French Riviera.

By 1931, Abdulmecid aimed to revive the caliphate with the support of Muslim notables from across the world. The former caliph's ambition was to establish a new home for the Ottoman legacy in the Indian subcontinent.

Shaukat Ali brokered a marriage between Abdulmecid’s daughter and the nizam of Hyderabad’s son a month before the World Islamic Congress. The firstborn son of the marriage would be caliph and ruler of Hyderabad.

Abdulmecid, Shaukat Ali and Hussaini aimed to use the World Islamic Congress to muster support for the revival of the caliphate. But for Hussaini, the goal was also to make Palestine a key player in the forging of a new Islamic political union.

As the congress approached, the Turkish republican government raised the alarm that a plot to restore the caliphate was afoot.

Ankara urged the French government to stop the former caliph from leaving for Jerusalem to no avail.

The controversy escalated, with the kings of both Egypt and what would become Saudi Arabia declining to attend.

In the run-up to the event and under pressure from Britain, the mufti declared in Jerusalem that “no caliph will be elected by the congress”, but then cryptically added that “we will deal with the question abstractly”.

In France, meanwhile, the former caliph’s monocled secretary Hussein Nakib Bey briefed American journalists that Abdulmecid “constantly corresponds with the Grand Mufti of Palestine” - before refusing to say any more.

By this point, Britain’s Foreign Office was desperate to ban the congress, but had to stand down after officials in Palestine warned that doing so would trigger an “Arab rebellion”.

As a compromise, Britain decided to refuse Abdulmecid entry to Palestine.

Resisting Zionism

When the World Islamic Congress eventually began on 7 December, it hosted 130 delegates from 22 countries. Notables included Riad al-Solh, the future prime minister of Lebanon, and Shukri al-Quwatli, who would become president of Syria.

The famous Egyptian reformist thinker Rashid Rida was also present, and Indian Muslim philosopher Muhammad Iqbal arrived in Jerusalem to great media fanfare.

The congress proceeded under the watchful and increasingly concerned eye of the British Mandate.

Mohammed Hussein Kashif al-Ghita, a prominent Shia sheikh from Iraq, led the delegates in prayer at the Al-Aqsa Mosque.

Mufti Hussaini gave a presidential address afterwards, describing the delegates as “friends of all and enemy of none".

The congress's goal, he declared, was “to provide a common platform for the Muslims of the world so that united they may fulfil the mission of Islam".

The delegates took an oath to “defend the holy places with every bit of strength” and called for a boycott of “Zionist goods”.

They also resolved to create an Islamic university in Jerusalem to attract Muslims from across the world and establish Palestine as a global hub of Muslim intellectual activity.

Most significantly, the congress resolved to form an Islamic company to buy up Palestinian land, as a counterweight to the Zionist settlement project.

British officials had been assured by Hussaini that the congress would not discuss controversial topics.

They were horrified therefore when delegates not only started discussing controversial political matters in great detail, but also carried a general resolution condemning colonialism and decreed that Zionism “directly or indirectly alienates Muslims from control over Islamic lands and Muslim holy places”.

When British High Commissioner Arthur Grenfell Wauchope asked the mufti for an explanation, Hussaini simply replied that he was unable to control what the delegates said.

For the British, the last straw was a particularly fiery and popular speech delivered by Abd al-Rahman Azzam, later to become the first Secretary General of the League of Arab States, condemning Italian atrocities in Libya.

The High Commission quickly ordered his deportation and Azzam was taken to the Egyptian border with a police escort. Palestinians in Gaza gathered to honour him as he passed through.

In 1931, Palestinian leaders presented a Palestinian Flag w/ a drawing of al-Aqsa to Shaukat Ali, the Indian leader, during the World Islamic Congress

— Zachary Foster (@_ZachFoster) August 29, 2023

Little has been written on the history of the Palestinian flag (c.1930-1964) Someone should change that! https://t.co/cedK3ns001 pic.twitter.com/2AQM26gSNE

Palestinian nationalist Awni Abd al-Hadi gave one of the most popular speeches, outlining what he described as the Zionist plan to take over Palestine.

He proposed a rejection of the British Mandate, to great enthusiasm from most delegates - although the mufti, anxious not to be arrested by the British, kept it out of the official list of resolutions.

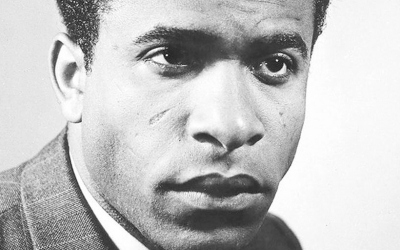

Another notable speech was delivered by Muhammad Iqbal, a strong supporter of the Palestinian cause on 14 December.

He warned against excessive nationalism and urged delegates to “inculcate the spirit of Muslim brotherhood in all parts of the world".

Iqbal declared: "The World Islamic Congress has great responsibilities.”

He warned of two “great dangers”, materialism and excessive nationalism: “I am not afraid of the enemies of Islam. My fear is from the Muslims themselves. Whenever I ponder, I bow my head in shame over the thought that we are not worthy of the great Prophet of Islam.”

Today, Iqbal is considered among the most influential Muslim philosophers of the twentieth century.

In an Urdu poem, The Trap of Civilisation, Iqbal made his views on British colonialism quite clear, saying of the Palestinians:

"Having been rescued from the 'tyranny' of the Turk,

These poor men have been caught in the clutches of 'civilisation'!"

Legacy

Although there were points of consensus, the Congress was wracked by internal disagreement. Voting blocs formed almost immediately and Egyptian delegates from rival parties heckled each other during speeches.

At one point editor Sulaiman Fawzi even had to be protected from a physical attack by the Jordanian delegate, Hamid Pasha bin Jazi.

On the face of it, the congress was a failure. The mufti followed up with an Indian tour in 1933, during which the nizam of Hyderabad donated money towards the proposed Islamic university in Jerusalem.

The nizam had previously donated to the upkeep of the Al-Aqsa compound, including paying for its chandeliers, and he funded an endowed hospice in Jerusalem dedicated to the revered twelfth-century Indian saint Baba Farid Gangshakar, who had once visited the city.

However, the university project eventually shuddered to a halt due to a lack of funds in 1935. And after the Arab Revolt began in 1936, the mufti left Palestine under threat of arrest.

Most controversially, the mufti became so anti-British that he ended up in Italy during the early years of the Second World War, making connections with the Nazis to try and secure a commitment to the independence of Arab states by the Axis powers.

Despite the congress's apparent failure, it was immensely significant. After the event, several Arab delegates stayed in Jerusalem to draft an Arab National Charter. The Congress established the Palestinian struggle as a pan-Arab and global Islamic cause.

It was the first time that an international body of Muslim notables had gathered to declare Zionism a colonial threat and the Palestinian struggle a cause for Islam.

Delegates were photographed displaying an early version of the Palestinian flag, which had the Al-Aqsa mosque drawn in the middle, dedicated to Shaukat Ali.

Over the decades, links between Indian Muslims and Palestine remained strong. Hyderabad's aristocratic Imam ul-Mulk family, custodians of Abdulmecid II's 1931 deed transferring the Ottoman caliphate to the princely state, established ties with the Palestinian Liberation Organisation after 1967.

Syed Vicaruddin, the family's head, hosted Yasser Arafat in Hyderabad twice and in 1998 the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Shaykh Ekrama Sabri, laid the foundation stone of a mosque in Hyderabad's Banara Hills.

The State of Palestine awarded Vicaruddin the Star of Jerusalem, one of the highest Palestinian honours given to a foreign national, in 2015.

The geopolitical legacy of the World Islamic Congress was also significant. In 1949, Hussaini convened an international conference in Karachi, in recently established Pakistan, as a sequel to the 1931 congress.

In 1951, also in Karachi, he chaired the World Muslim Congress, attended by representatives of 32 Muslim countries.

Its findings provided the foundation for the eventual establishment of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference in 1969, eventually renamed the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, which exists to this day.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.