Death of a dream: New York's Yemenis caught between war and Trump's ban

Ali did everything he was supposed to.

For two decades he endured gruelling hours working in New York bodegas – the small 24/7 convenience stores-cum-delis found across the city – and earned enough money to build a four-storey house in his native Yemen.

During a 2015 visit, he got married, planning to move his wife from their village outside Ibb to their new home in Sanaa.

Ali’s dreams were shattered later that year when an air strike by the Saudi Arabia-led coalition involved in Yemen’s bloody conflict destroyed his empty house. It changed his future in an instant.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“Now I have to work 20 more years to rebuild it," he jokes sarcastically.

Ali didn’t give up. He tried to rebuild his life and reclaim his future. He again returned briefly to Yemen and became a father in 2017.

But Ali has only met his son through a mobile screen, as his family cannot join him in the US due to Washington’s current immigration policy. Given the ongoing war in Yemen, he fears that they will be dead within 10 years. (Like the other workers interviewed, he did not give his full name amid concerns for family safety).

Ali’s story, though tragic, is not unique.

Yemeni in the US: Parallel lives

New York and other American cities are full of stories like Ali’s, of Yemeni-Americans who made a life for themselves in the US, only to see their imagined futures transformed for the worse, facing insurmountable obstacles to reunite with their families and unable to enjoy the fruits of their hard work.

Yemenis have owned and operated delis across the United States for more than half a century. The Yemeni American Merchants Association (YAMA) estimates that there are as many as 5,000 Yemeni-run bodegas in New York City alone.

Youssef Mubarez, YAMA’s public relations director, points to Yemenis’ “work ethic, entrepreneurial impulse, business acumen and family and community relationships” as the primary drivers of their success.

The majority of these Yemenis hail from Ibb, one of Yemen’s most populous and beautiful provinces. Colloquially known as “Ibb the Green,” Ibb is famous for its fertile land and terraced landscape, dotted with dozens of mini-palaces, many of which are owned by Yemeni-Americans.

Mubarez’s grandfather, Abdullah Mubarez, came to the US during the 1960s and opened a bodega in Brooklyn. His wife and children remained in Yemen, where Abdullah would return for several months at a time. Youssef’s father joined Abdullah when he was 10, working at the family-owned stores before eventually opening his own at 14.

Like so many Yemenis in the New York City bodega business, the Mubarez family established roots in the US while maintaining deep ties back home.

These new American citizens kept one foot firmly planted in both worlds, largely by keeping their immediate families in Yemen and returning periodically for long visits. They split their adult years between a work life in the US and a family life in Yemen, before ultimately retiring back home.

Mubarez explains, “When they are here, they’re American. When they are in Yemen, they’re Yemeni. By going back and forth, they retain both cultures.”

Twin punch of war and travel ban

But this distinctly Yemeni version of the American Dream has taken a catastrophic turn in recent years.

The patterns of migration and visitation that allowed Yemeni-American bodega workers to maintain their composite identities – and in many cases, split lives – have been severely disrupted by two factors.

First, the conflict that has engulfed Yemen since early 2015 has created the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. In April 2019, a United Nations report predicted that by the end of the year, the conflict will have claimed the lives of more than 230,000 Yemenis, the majority due to severe disease and famine.

Second, in January 2017, US President Donald Trump introduced a travel ban on the citizens of several Muslim-majority countries, including Yemen, from entering the US.

According to the State Department’s annual reports on visa issuances, Yemeni nationals received nearly 80 percent less immigrant visas to the US in fiscal year 2018 compared to 2017. This includes a more than 75 percent decrease in visas issued to Yemeni nationals with US citizen relatives.

Fuad, a 35-year old, came to New York City as a teenager to work at his cousin’s deli. He always dreamed of an “American life” with his family living together, rather than dividing his time between Yemen and the US.

In 2016, he married in Ibb at the urging of his relatives. But three years later, he continues to wait for his wife’s visa. His life has been beset by tragedy from afar, including the death of their infant daughter.

Fuad is left asking when – and if – his own American dream will be realised.

'I wake up in the morning, praying that nothing happened to them'

- Fuad, Yemeni deli worker

After he visited Yemen for six months in 2018, his wife delivered their second child in February of this year. Like Ali, Fuad has never met their son, named Abdel-Fattah after Fuad’s brother, who was killed during the war and left behind nine children.

Fuad plans to visit again next year, despite the dangers. Until then, the anxiety for his family’s safety never relents. “I wake up in the morning, praying that nothing happened to them.”

Suleiman, who is now in his early 40s, arrived in New York City in 1997. He began staffing delis for more than a decade until he was able to purchase his own with his brother.

With his wife and two daughters remaining in Yemen, Suleiman lived the dual existence that defined this community for so long.

But after a bomb shattered the windows of their Ibb home in 2015, his younger daughter – who was four at the time – begged him to get them out. Suleiman was fortunate: he was able to secure their US visas prior to the travel ban. He then returned to Yemen to retrieve his family, taking them on an arduous journey to the US via Aden, the Red Sea and Djibouti.

Suleiman’s eldest daughter, now 14, insists that she wants to return to Yemen someday – a choice he plans to give his children.

His future and that of his family, including two sons born in the US, is in America. The war has forced him to live in New York City, where he hasn't taken a day off in three years.

But Suleiman’s fears for his extended family in Yemen remain. “You work all day, but you’re also thinking about your family,” he says. “Are they okay? Are they alive?”

Diaspora asserts itself

Once commonplace, a life split between Yemen and New York City is inconceivable in 2019. And the dream that many still hold of retiring to Yemen is rapidly fading.

This stark reality, combined with their existential fear for their families, has led many bodega workers with US citizenship, like Suleiman, to bring their dependents to the US. But for countless others, like Ali and Fuad, the travel ban has proven an insurmountable barrier.

Yet despite the practical and emotional toll that they bear, thousands of Yemenis employed at New York City’s ubiquitous delis continue to find ways to remain connected to Yemen.

They spend hours behind their counters, working and speaking with friends and family back home. They pull longer shifts to send money to family impacted by the war and desperate for money.

Some even brave trips to Yemen, despite the obvious danger.

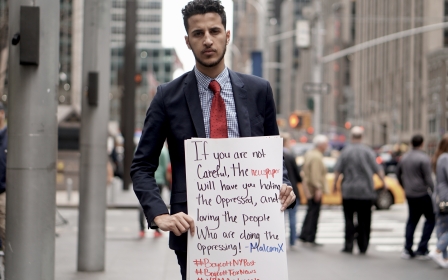

Many have found an outlet in activism, demonstrating their agency and influence through political and economic action. In 2017, for example, thousands of bodega owners shut up shop and protested on the streets of New York City against the travel ban.

'God is good. Nothing stays the same forever'

- Ali, Yemeni deli worker

According to Youssef Mubarez of YAMA, Yemeni-Americans were always politically engaged. “Once we realised our influence – not merely as American citizens, but also as merchants and businesspeople – we stepped up to strengthen our community.”

This assertiveness has continued to grow. In April, hundreds of Yemeni-owned delis began a boycott of the New York Post due to its front page that targeted Muslim-American congresswoman Ilhan Omar.

The bodegas of New York City are full of stories of heartache, their tellers palpable with anxiety. But they also exhibit extraordinary resilience, courage and even hope.

“God is good,” says Ali. “Nothing stays the same forever.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.