From Zanzibar to Oman: A bittersweet exile

More than half a century has passed since a revolution forced them to leave their homeland in East Africa for the hard, desert landscape of Oman, a country which at that time had only one hospital and three primary schools.

Since then, Oman has transformed out of recognition - but for the Omanis of Zanzibar the memories and traumas of that time are difficult to process.

At the Coconut House, traditional food from Zanzibar - including a famous octopus dish - is served up to the residents of Muscat, Oman's capital. A man in his fifties walks in and whispers a greeting in Swahili.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Across the city, a range of cuisine from Zanzibar can be found, all of it popular with Omani families. Specialities like mohogo, kisamvu, maharagi, mandazi, sambusa, chicken and fish curries subtly blend East African, Arab and Indian flavours, ingredients and spices.

This mix of flavours reflects the history of Zanzibar and speaks to the long-standing ties between the Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa and the Gulf sultanate.

Oman has had trade and migration links to the region going back centuries. More than 100,000 Omanis were born in East Africa or have family ties to the region, according to estimates, although a census has yet to be conducted.

Like millions of people across East and Central Africa, Zanzibari Omanis speak Swahili, a Bantu language that has been enriched with vocabulary from Arabic, German, Portuguese, English, Hindustani and French during centuries of colonial presence in the region.

Revolution arrives

This era came to a violent end in 1964 in the Zanzibar revolution when the Sultan of Zanzibar, as well as the mainly Arab government, was overthrown. The sultan fled with his family to London.

Many factors played a part in the revolution. The CIA reported in 1966: “Africans have felt hostility towards the Arabs, who have been the landed aristocracy for whom the Africans have worked as indentured servants.”

Academic research, led by former Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) professor Nafla Soud al Kharusi in The Ethnic Label Zinjibari, estimates that during the Zanzibar Revolution, African revolutionaries killed 5,000 to 15,000 Arabs: the BBC puts the number as many as 17,000 people killed, including Arabs and south Asians, with thousands more imprisoned.

East-African born Omanis interviewed by MEE noted that Arabs were not the only ones targeted: many local people involved in governmental positions were also massacred. “It was indiscriminate killing,” Hareth al-Ghasani, an Omani who was born in Zanzibar, told MEE.

"African revolutionaries killed my father's sister who was pregnant, cut her stomach and removed the baby,” Zanzibar-born Omani artist Madny al-Bakry remembers.

Al-Bakry, who paints Arabic calligraphy and also Zanzibar landscapes, left the island, where his father ran a dairy business, in 1971.

“On the day of the revolution, I woke up and saw guns all over the living room table. ‘What is going on?' I thought. And yet, my father asked me to go to deliver milk to our clients because the regular delivery man did not show up.

“Once in the street, I saw an Indian man on his scooter screaming, ‘They are coming, they are coming,’ so I thought, ‘Who is coming?!’ I did not want to run away and let people think that I was scared but when I saw an Omani guy holding a gun to protect the street, I got into our house."

'African revolutionaries killed my father's sister who was pregnant, cut her stomach and removed the baby'

- Madny al-Bakry, artist

Like many other Arab Zanzibaris at the time, al-Bakry’s father was arrested during the revolution. “My father got detained successively for eight and six months. When he ended up in jail for the third time in a row, I took the decision to escape Zanzibar,” said al-Bakry, who believes a change “had to happen”.

According to the artist, many descendants of Zanzibar-born Omanis believe that the archipelago's Arab elites had been living "in a bubble, which prevented them from understanding a surge in African nationalism among the population.

“We saw it coming. A minority cannot rule a majority,” al-Bakry told MEE.

From 1964 onwards, the crisis pushed thousands of Arab families into exile for a years-long journey towards their ancestral homeland. However, Said bin Taimur, the sultan of Oman at the time, feared outside influences and made it difficult for most Omanis born in East Africa to return.

“I knew I was from a country named Oman but I never thought of returning,” Zanzibar-born Omani, Hareth al-Ghasani, told MEE. “From my young age, I knew I have roots in Oman because on my birth certificate it is written that my father is Arab… and we have letters in Arabic from the time when my father got married.”

Harsh homecoming

Oman during the 1960s was very different from the Omn of today. As described by MEE’s Ian Cobain in The Guardian: “The sultan banned any object that he considered decadent, which meant that Omanis were prevented from possessing radios, from riding bicycles, from playing football, from wearing sunglasses, shoes or trousers, and from using electric pumps in their wells.”

Although al-Ghasani did not live in Oman under bin Taimur, he was aware of the restrictions that the sultan had imposed. “He did not want us to influence a traditional society and would not allow anything, not even a bicycle,” he says.

Al-Ghasani remembers the day in 1978 when he returned to Oman from Egypt where he had lived for two years. “If you live in Cairo and come to Muscat in 1978, it is like coming from rural America and going to New York, those people were slow.”

Al-Ghasani was born in Zanzibar in 1958, where his father was the under-secretary for the Ministry of Agriculture. The family left the island in 1974 (he now holds a PhD from Harvard and is a businessman). “My father was from a large family in Zanzibar and did not leave following the revolution, so we stayed."

He adds: “My mother was working for a local radio station. During the revolution, there were so many harassments by the revolutionaries, so my father told her to stop going to work. My uncle, who was part of the party that was overthrown, was arrested, but not my father who had always been a technocrat who did not like politics."

Following a 1970 palace coup orchestrated by British intelligence to remove Oman’s conservative ruler and replace him with his son, Qaboos, bin Taimur was taken by the British to London, where he lived out his last days in a hotel.

Soon, East Africa-born Omanis started to return to the Gulf as the new sultan invited them to join in nation-building and granted them Omani citizenship.

Madny al-Bakry lived in Tanzania, Kenya, Somalia, Yemen, Kuwait and the UAE, until he finally reached Muscat in 1974. There, he says, he discovered what he calls a “mediaeval-like country", where only five percent of the population could read and services were rudimentary.

The contrast with the flourishing economy that had existed in Zanzibar, where Omani merchants would export products all across the region, was a shock to the new arrivals. As al-Bakry recalls: “There was nothing, no infrastructure, no schools and only one road. This place was not for human beings!”

According to Sultan Qaboos University’s Professor Ibrahim Noor Sharif al-Bakry, East Africa-born Omanis flew back at the right time to “help” Qaboos bin Said to build up the country. It meant the Gulf state experienced the world’s fastest progress in the Human Development Index during the four decades to follow.

As Oman gradually strengthened its economy, so the skills of many East Africa-born Omanis educated in Zanzibar - among them doctors, teachers and engineers - were coveted. Al-Ghasani, who had not even finished high-school at the time, was able to secure a job at Petroleum Development Oman (PDO), the country’s main energy company.

Returnees - commonly referred to as Zinjibaris ("a person from Zanzibar") - started to succeed in business, the arts and gain access to prominent government positions.

But some Omanis born in the Gulf felt challenged by the professional achievements of those born in Zanzibar. The population in Oman felt "unfairly treated, as they perceive themselves to be the true ‘natives’ and therefore deserving of more access to economic success... the discourse of differentiating between ‘us’ and ‘them’ gained momentum,” noted Nafla Soud al-Kharusi in his 2013 study for the Sultan Qaboos University.

“We had to start our life all over again but some Omanis would look down at us,” al-Bakry recalls.

'We had to start our life all over again but some Omanis would look down at us'

- Madny al-Bakry

Furthermore, East Africa-born Omanis, influenced over centuries by a cosmopolitan Zanzibari society, were socially far less conservative than their Oman-born countrymen and were often stereotyped as too Western, “non-traditional” or “unpatriotic”, Nafla Soud al-Kharusi wrote in her study.

For example, Madny al-Bakry, before he returned to Oman, lived in Kuwait and the UAE, where he worked in nightclubs as a singer and formed his own band.

al-Kharusi’s study says that “because of previously living overseas, they [East Africa-born Omanis] have adopted different cultural and social norms often apparent in their marriage and funeral rites, as well as in their women’s less conservative dress."

Following decades of integration into Omani society, the long-standing Zanzibari contribution to the sultanate was officially recognised when Sultan Qaboos appointed a significant number of them as ministers and under-secretaries following protests in 2011.

Back in Zanzibar though, East Africa-born Omanis have largely failed to be accepted. Hareth al-Ghasani - who returns to Zanzibar for visits - says an under-lying anti-Omani sentiment is still evident.

“People in Zanzibar do not feel good, because we got kicked out of Zanzibar from 1964 onwards and come back with a wealthier lifestyle than them. ‘You still have a better life, a better car, how come?’ they say.

“The same country where I was born in 1958, Zanzibar, now tells me that I am not a full human being. I feel dehumanised.”

The legacy of slavery

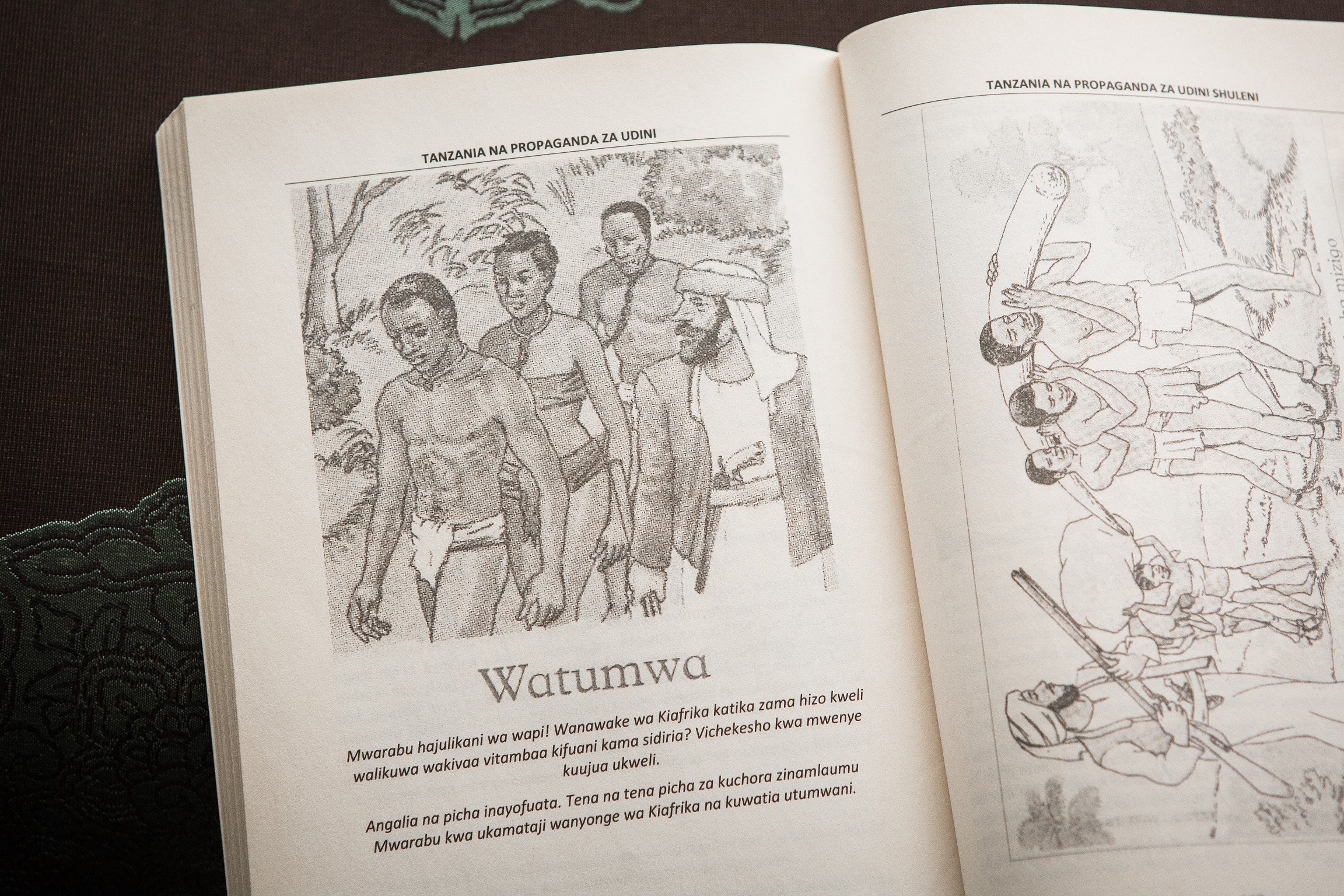

This antagonism can, in part, be traced back to the centuries-old position of Zanzibar as a slave hub in East Africa, with much of the trade controlled by resident Arabs.

Although Sultan Said of Muscat and Oman agreed to end the slave trade in 1847, the export of slaves continued into the 20th century.

According to historian Matthew Hopper’s book, Slaves of One Master: Globalization and Slavery in Arabia in the Age of Empire, of 800,000 Africans transported to the Arab Gulf in the latter half of the 19th century and until the 1930s, the vast majority were abducted from East Africa and shipped to ports in Yemen and Oman.

This version of events is not accepted by many Zanzibari Omanis. Born in 1941 in Zanzibar from Omani ancestors who once ruled the Somali city of Merca, Ibrahim Noor Sharif al-Bakry wrote a book in Swahili on Oman-Zanzibar history. He says that there was “not a single Arab” roaming the vast inland areas of East Africa with the intention of capturing slaves. “Those claims are untrue,” he told MEE.

Others are more balanced Looking at the horizon of the Gulf of Oman from the living room of his bright modern house, al-Ghasani recognises the participation of East Africa-born Omanis in the trade.

“You cannot deny that Omanis and Arabs were involved in slavery,” he says. “You cannot deny it. Omanis were involved, the Indians financed the slavery, the African chiefs provided the slaves, so the blame should not be put only on Arab Omani Muslims. If you deny that Oman contributed, then you become an Arab apologist.”

This controversial area of Omani history is not widely taught in Omani schools. According to a study led by Okawa Mayuko, an associate professor at Japan's Kanagawa University, slavery is “completely absent from Omani textbooks” which, in contrast, put an emphasis on the Oman-led spread of Arab-Islamic civilization to East Africa. Mayuko believes it “reveals an ideology of the Omani government to conceal slavery.”

Forgotten history

Al-Ghasani says that there is a lack of wide understanding in the Gulf and East Africa about what happened during the Zanzibar Revolution.

“Even Omani government members still today do not know what happened in Zanzibar," he says. "The Zanzibar government does not know either. There is so much ignorance that surrounds this part of our history, even about slavery.”

In Oman, the impact of Zanzibar's revolution 1964 and subsequent exile of Omanis born in East Africa continues to resonate.

One former military advisor to Sultan Qaboos, who prefers to remain anonymous on grounds of safety, is still deeply scarred about the killing of his father by African revolutionaries. “It hurts to talk about it," he said "If I had the power, I would go there and kill everyone. My family had been living there for generations, and overnight we had to leave everything.”

Notwithstanding such challenges, al-Ghasani foresees potential in forming prosperous economic relations between Oman and Zanzibar with the Sultanate’s investments in the Tanzanian archipelago reaching $500m.

'I am very hopeful because the era of African nationalism is over and decolonisation is over too-

- Hareth al-Ghasani

He believes in the opportunities relating to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a global transport network of which Oman’s Duqm Port is part. The Tanzania government, however, has suspended the construction of the BRI’s $10bn Bagamoyo Port after rejecting the terms offered by Beijing.

There are also moves to find a consensus over Oman's and Zanzibar's shared history. In 2018, Oman signed an agreement with the island to digitise “documents and manuscripts relating to the historical relations between the two countries”, the Times of Oman reported.

Al-Ghasani says that his children don't know anything about the Zanzibar revolution. He hopes that a new generation of leaders in Tanzania, coupled with Omani willingness to look for convergence in East Africa, could open the way to economic partnerships.

“I am very hopeful because the era of African nationalism is over and decolonisation is over too,” he says.

Editor’s note: Sections of this story were re-edited on 10 December to clarify certain details and comments.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.