War on Gaza: Why is Israel insisting on controlling the Philadelphi and Netzarim corridors?

Negotiations for an end to the ten-month-long war in Gaza have recently centred around two buffer zones controlled by Israel’s military.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has declared that under a truce agreement, there would be no Israeli withdrawal from the Philadelphi and Netzarim corridors.

The Philadelphi Corridor, a buffer zone between Egypt and Gaza, has existed for more than four decades, and has been maintained on the basis of two bilateral agreements between Cairo and Israel.

The Netzarim Corridor, meanwhile, cuts through central Gaza, and was created in recent months by Israeli forces to monitor Palestinians.

Palestinian groups have firmly rejected Israeli demands on maintaining a military presence in the two corridors, and believe that Netanyahu added these demands to derail negotiations.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye breaks down what you need to know about the two zones.

What is the Philadelphi Corridor?

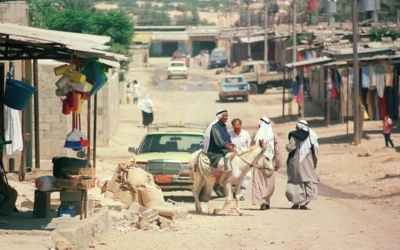

The Philadelphi Corridor is a 14km-long, 100 metre-wide demilitarised buffer zone that runs along the entirety of the boundary between Egypt and Gaza.

It runs from the Mediterranean Sea to the Kerem Shalom crossing at the meeting point of Gaza, Egypt, and Israel.

It was first set up under a 1979 peace treaty between Egypt and Israel and is named after the Israeli military’s codename for the demilitarised zone.

At the time, Israel had agreed to end its 12-year occupation of Egypt’s Sinai peninsula but continued to occupy the Gaza Strip in Palestine.

Egyptians refer to the area as the Salah al-Din corridor, named after the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty who defeated the Crusaders in Jerusalem in 1187.

The corridor includes the Rafah crossing, the only transit point between Egypt and Gaza.

Under the 1979 agreement, Israel was allowed to deploy limited armed forces in the corridor, consisting of four infantry battalions, their military installations, and field fortifications, along with UN observers.

It was not allowed to deploy tanks, artillery, or anti-aircraft missiles, except individual surface-to-air missiles.

The stated aim of these Israeli forces was to stop weapons from entering Gaza via Egypt.

When did Israel leave the buffer zone?

In 2005, Israel withdrew its armed forces from Gaza as part of a "disengagement plan," including from the Philadelphi Corridor.

It also withdrew 9,000 Israeli settlers living in 25 illegal settlements.

The corridor then came under the control of Egypt and the Palestinian Authority (PA). The latter controlled the Gaza side of the buffer zone.

Under a 2005 agreement signed between Egypt and Israel, known as the Philadelphi Accord, Egypt would be allowed to deploy 750 border guards to patrol the corridor for counterterrorism and non-military purposes.

That included prevention of smuggling and infiltration.

Two years later, Hamas took full control of the Gaza Strip, ending the PA’s joint administration of the buffer zone.

Since then, Israel has enacted a land, air, and sea blockade of the Gaza Strip.

The Rafah crossing - part of the Philadelphi Corridor - has been opened intermittently by Egyptian forces during that time.

As such, there was a proliferation after 2007 of tunnels built between Gaza and Egypt’s Sinai, both for smuggling goods and arms, but also for family reunions.

Egyptian authorities destroyed more than 2,000 of these tunnels linking Sinai and Gaza between 2011 and 2015, citing security concerns.

What happened to the corridor during the current war?

The Rafah crossing was the only entry and exit point into the besieged enclave not controlled by Israel - but that changed earlier this year.

In January, three months into Israel’s war on Gaza, Netanyahu declared Israel’s aim of re-occupying the buffer zone.

"The Philadelphi Corridor - or to put it more correctly, the southern stoppage point [of Gaza] - must be in our hands," he said at the time.

"It must be shut. It is clear that any other arrangement would not ensure the demilitarisation that we seek."

Egypt responded by stating that such an action would violate the 1979 treaty between the two countries.

After months of threatening a ground operation in southern Gaza’s Rafah, Israel seized control of the Palestinian side of the Rafah crossing on 7 May.

Days later, it seized the Palestinian side of the Philadelphi Corridor too, marking the first Israeli troop presence in the buffer zone since 2005.

Israeli officials said in late May that it had found 20 tunnels, and 82 access points to tunnels, upon taking over the corridor.

What is the Netzarim corridor?

The Netzarim Corridor is a 6km stretch of land that divides northern and southern Gaza.

It was established by Israel’s military during the current war and stretches from the Israeli boundary with Gaza City to the Mediterranean Sea.

The arbitrary line is named after Netzarim, one of the illegal Israeli settlements that existed in the Gaza Strip before the Israeli withdrawal in 2005.

That name could be a nod at re-establishing illegal settlements in the Strip - something far-right Israeli ministers have frequently called for since 7 October.

The Netzarim route consists of military bases and is used by Israeli forces to monitor and control the movement of Palestinians between northern and southern Gaza. It has also been used to launch military operations.

Analysts say that Israeli control of the newly-created corridor is an attempt to permanently dictate life in Gaza beyond the war, without necessarily occupying the entire territory.

What has Israel said about the corridors during talks?

Netanyahu has vowed that Israel will retain military control of both corridors, as well as the Rafah crossing, and has added those demands into ceasefire negotiations.

“Israel will not, under any circumstances, leave the Philadelphi corridor and the Netzarim axis despite the enormous pressure it is under to do so,” the prime minister said.

This week, Israeli negotiators reportedly informed Netanyahu that his insistence on maintaining a presence in the Philadelphi Corridor was the main obstacle to a truce deal.

'Israel will not, under any circumstances, leave the Philadelphi corridor and the Netzarim axis'

- Benjamin Netanyahu

These conditions did not feature in a ceasefire proposal endorsed by US President Joe Biden in a speech on 31 May, and a subsequent UN Security Council resolution on 10 June.

Both the Security Council resolution and the Biden-approved plan referred to negotiations that would lead to the complete withdrawal of Israeli forces from Gaza.

Israel has referred to its new demands on the Philadelphi and Netzarim corridors as “clarifications” to the earlier Biden-endorsed proposal.

How did Hamas and Egypt respond?

Basem Naim, a member of Hamas’s political bureau, told MEE that Hamas had already welcomed the Security Council Resolution and “confirmed its readiness for immediate implementation” in early July.

He said that Netanyahu responded with “more massacres and killings” and “new conditions” including not withdrawing from the two corridors and the Rafah crossing, inspecting displaced Palestinians returning to northern Gaza, and changing the terms of an agreed prisoner exchange deal, among other alterations.

“The US administration and the international community must put an end to this recklessness and pressure Netanyahu and his fascist government to halt the aggression and sign the ceasefire agreement,” Naim said.

Earlier this week, three senior Egyptian sources told MEE that Egypt and Israel had reached an understanding that would allow for an Israeli security presence along the Philadelphi Corridor.

According to the sources, one option is for Israel to maintain boots on the ground. The alternative is to replace the troops with an underground barrier, electronic monitoring equipment, and occasional patrols.

The officials told MEE that Egypt would agree to these options if Palestinian factions, particularly Hamas, supported them.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.