Listening to Istanbul: Preserving its past and present through sound

ISTANBUL, Turkey - On a recent, muggy evening in the Galata neighbourhood of Istanbul, crowds piled into an old, disused factory, and visitors slowly began noticing unusual sounds.

They were coming from the outdated industrial machinery in the centre of the room: a simit (Turkish sesame-encrusted bagel) vendor selling his wares, the blare of a ferry horn, and from somewhere in a corner, the ringing bells of the city’s now-defunct nostalgic tramway.

It was opening night of Protocinema’s Kiralık, Satılık (For Rent, For Sale), a group art exhibition where sound plays a subtle but important role in the examination of Istanbul’s rapidly changing urban landscape. It was also the first time Pinar Cevikayak Yelmi witnessed her work in a contemporary art context.

Usually her research is accessible via computer screen and headphones, but here, her Soundscape of Istanbul project audibly illuminates a room filled with sculpture, photography, and drawings.

The many sounds of Istanbul

For the past five years, 32-year-old Yelmi has immersed herself in the cultural sounds of Istanbul’s present, paying close attention to how they represent the city where she was born.

Originally an industrial design student, her interest in sound developed during her masters’ studies in visual communications, examining how sound and experience, united with design, can illustrate a broader picture of heritage.

“This is basically a cultural heritage project,” Yelmi told Middle East Eye. “The first motivation is to preserve representative examples of these sounds because they are really important for cultural heritage, cultural memory and for cultural identity, and they are all changing.”

In the field

Istanbul is a big city; spanning both sides of the Bosphorus, it is home to over 14 million people and it is growing. An array of sounds, both old and new, contribute to the everyday soundscape of the city, and in recent years many areas, like the ports, have undergone massive renovation efforts. In a city that is so large, it wasn’t easy for Yelmi to decide where to begin recording her project.

The first motivation is to preserve representative examples of these sounds because they are really important for cultural heritage

- Pınar Cevikayak Yelmi, urban sound researcher

“When I first started this project, I was trying to capture my favourite sounds,” Yelmi told Middle East Eye. “But then I thought: okay, this is my life in Istanbul, but there are so many other lives in Istanbul, so other people are not necessarily hearing or listening to similar sounds as me.”

She began distributing an online survey to around 400 participants, asking questions about the sounds people associate with the city, their neighbourhoods, and particular times of year.

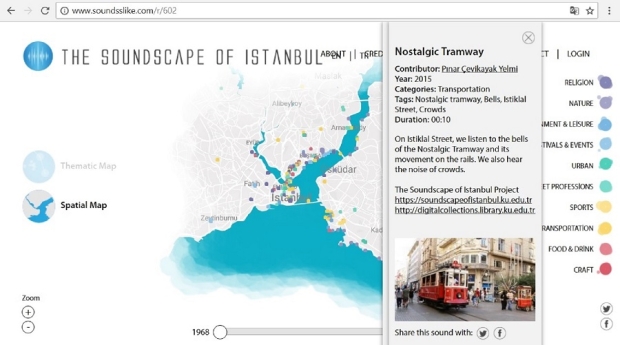

The results were surprising: sounds that she thought of as iconic, such as the nostalgic tramway, which has been uprooted from the centre of Istiklal Street in the months since recording for renovations, or the portside seagulls, were low on the list.

“I analysed all of these results, and made up a detailed sound list, as well as a timeline of the sounds, and categorisation, such as food and drink sounds, transportation sounds, religious sounds,” Yelmi said, noting that people may personally value sounds they hear rarely, rather than in day-to-day life.

There is not much work being done on these issues, preserving sound, even around the world

- Emre Yucelen, Turkish musician

“There are sounds that we hear daily – like the Turkish bagel vendors and the tea sellers, but there are some sounds that we hear only once a year, like national or religious festivals, and commemorations, and this actually determines their value and their place in society,” she added.

Armed with a sound recording plan that resembled a calendar, Yelmi and various assistants headed out into the city, prioritising sounds that were at risk, like the fishermen at the ports.

One of these was a popular street for nargile (shisha) in Tophane that was bulldozed to make way for the Galat Port project and she couldn’t quite track down a wandering boza (a low-alcohol drink) drink seller.

By the end of the year, however, she had amassed around 300 individual examples of Istanbul’s iconic cultural sounds, which were then made public on the Koc University archive website.

Making a map

“I always had this idea to encourage people to contribute to the archive,” Yelmi said, describing her decision to take her research one step further, after the recordings had been archived online.

“We wanted people to create their own soundscapes and to play with the sounds, so that we purposefully allowed them to play three sounds at the same time.”

Through this website, Yelmi opened up her archive to others and allowed them to contribute. Anyone with an Mp3 recording they want to share can upload it to this crowdsourced map and enter the details of the sound. Much to Yelmi’s delight, someone was able to track down an elusive boza seller and upload a recording of his voice.

When Emre Yucelen, a Turkish musician who has been compiling his own Istanbul sound recordings since 2006, met her last year, the two joined forces.

My recordings were primarily for relaxation and meditation, because living in a huge city like Istanbul, it is just totally noise

- Emre Yucelen, Turkish musician

“My recordings were primarily for relaxation and meditation, because living in a huge city like Istanbul, it is just totally noise,” Yucelen told MEE, who focuses many of his recordings on quieter aspects of the city; the sounds of nature in the parks, or muezzins calling for prayer outside the centre of the city.

Yucelen contributed 129 recordings to the map, happy to unite his personal project with one that is growing.

“Everything about sound is precious to me,” he said. “There is not much work being done on these issues, preserving sound, even around the world, but I think it is a very valuable work. Istanbul is completely changed, and now the only thing left in Istanbul is noise.”

For rent, for sale

The interactive website is also reaching far and wide – with Yelmi teaming up with international sound archives, like Europeana, and continuing her research by bringing the Soundsslike platform to institutions like the British Library. It can also be applied to other cultural endeavours.

The exhibition is about the city and how it’s changing

- Pınar Yelmi, urban sound researcher

When curator İbrahim Cansızoglu began putting together Kiralık, Satılık, he wanted to show how Beyoglu's urban landscape was changing by using the neighbourhood’s many recent “for rent, for sale” signs as his starting point. He knew that sound could be a valuable addition to the visual elements he was uniting in this abandoned factory space – it was just a matter of finding the right sounds.

“It shapes society, and people’s conceptions about how they live and how they understand society,” Cansızoglu said.

Within the Soundscape’s hundreds of sounds, Cansızoglu was able to unite four separate recordings to complement the multimedia installation of Antonio Cosentino, an Italian-Armenian artist who was born in Turkey. The installation explores a fictional account of Istanbul, sliced in half by a giant wall that separates a modern, paved over, redesigned part of town with the older, historical area.

“In a way, everybody is attracted to the sound element of the exhibition,” Cansızoglu said.

“Other exhibitions using The Soundscape of Istanbul were much more focused on presenting the archive, and we wanted to do that also, but we didn’t want to separate or carve out a space in the exhibition just for them. We wanted them to be mounted within the idea of this group show, so it was in a way, both new for Pınar and me, but it was an enriching experience for both of us and the audience," he added.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.