The Mummy returns: How Egypt is waging war against the smugglers

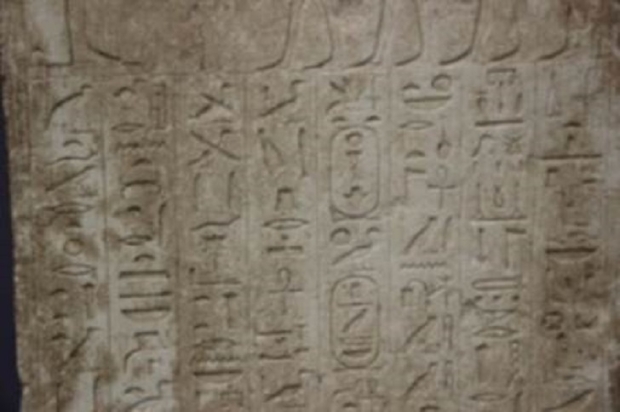

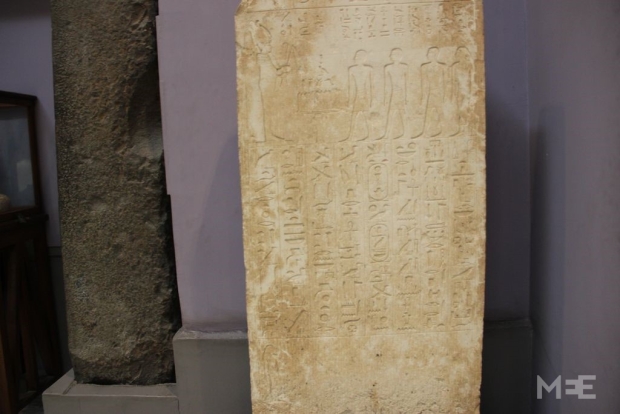

CAIRO - In July, Egypt managed to recover, from an auction hall in Paris, the relief of King Nectanebo II of the 30th dynasty, which was stolen from the Saqqara necropolis in the 1990s.

In September, a Pharaonic ushabti funerary figurine dating back to the 19th dynasty was retrieved from Mexico. The statuette, smuggled out of Egypt after an illegal excavation, was discovered by a Mexican citizen at his newly purchased house.

These are just two examples of the ongoing battle to retrieve a huge quantity of treasures, which have been plundered over many years, that is being waged by the Egyptian antiquities department and its allies abroad.

Since the security chaos that broke out after the 2011 revolution, an estimated $3 billion worth of antiquities have been trafficked abroad, making the job of preserving and protecting Egypt's cultural and archaeological heritage hugely challenging.

"Look, this is a mummy mask from the Greco-Roman period. A French art gallery sent it to me today," said Shabab Abdel Gawad, head of Egypt's antiquities repatriation department, which was founded in 2002, holding up a picture on his mobile phone. He hinted at the fact that it is just one of the many pieces of the past that have been stolen, smuggled out of Egypt, and sold around the world.

The stealing of antiquities is a practice as old as the pharaohs. From early gangs of looters pillaging tombs; to invading armies taking entire obelisks back home, or international delegations sending artefacts abroad by means of gift or trade; to foreign archaeologists receiving part of the objects found in their excavation via "partage" arrangement; to travellers buying antiquities from dealers with no record of transactions ever having been made.

Three years after the Malawi National Museum in the Upper Egypt city of Minya was plundered during the violence that followed the overthrow of president Mohamed Morsi, the museum reopened on 22 September this year.

Minya has been the site of some of the worst acts of robbery and vandalism toward Egypt's heritage sites. In August 2013, more than 1,000 ancient objects were stolen and 48 were destroyed. In time, the Egyptian authorities were reportedly able to retrieve 950 out of the 1,089 objects recorded in the museum's inventory. As recently as February, two Antiquities Ministry security guards at the Deir al-Barsha archaeological site in Minya Governorate, were shot dead by armed robbers attempting to loot the site.

It was not until 1983 that Egypt enacted law number 117 on the protection of antiquities, which states that all monuments and artefacts discovered or found in the country are the undisputed property of the Egyptian state, prohibiting possession and trade of antiquities.

Under this law, people caught smuggling antiquities can face prison terms of hard labour and fines ranging from 5,000 to 50,000 Egyptian pounds ($565 - $5,635). Anyone found removing or detaching an antiquity from its place can also be sentenced to one to two years in prison and/or handed a fine of 100 to 500 pounds ($12 - $57).

Despite this, countless objects continue to be carried off or traded illegally from Egypt, finding their way into museums and private collections worldwide.

Poor security

The trafficking of stolen cultural goods has become a serious concern since the 25 January 2011 revolution amid an absence of security and lack of control by authorities.

Images of vandals breaking through the ceiling of Cairo’s Egyptian Museum in January 2011, looting and damaging artefacts like mummies and statues, are alive and well in the minds of Egyptians. And three years later, Cairo’s Museum of Islamic Art was hit by a bomb blast, destroying hundreds of items.

After the uprising, poor security and a lack of supervision at historical sites left a void that was allegedly filled by jobless individuals who turned to an illegal means of survival. This is still the case today as Egypt has been struggling to revive its battered economy.

"Behind Egypt’s antiquities black market trade are mainly organised gangs, specialised in the trafficking of ancient relics, and poor residents making illegal excavations at archaeological sites," asserted French internal security attaché Jean-Charles La Monica.

Although security has been largely restored in museums and archaeological sites across Egypt in the last three years, it still remains hard to control the unchecked flow of objects going out of the country.

La Monica explained that criminal networks of diggers and traffickers manage to get stolen artefacts out of the country by issuing deeds of sale that cover the tracks of their origins. Without a solid provenance, dealers, collectors and museum curators cannot know whether an item is fair or foul. Objects whose documentation seems to be in order may be put up for sale by auction houses.

Looted antiquities effectively start their journey being tainted in illegality and end up being clean, making an inviting source of profit for organised groups of thieves.

"We are talking about objects with an extremely high fraudulent financial value going from 300 to 1 million euros," the French attache, a chief superintendent, estimated.

Recovery mission

Although it is impossible to assign an exact value on the artefacts stolen from Egypt, according to the US-based Antiquities Coalition, some $3bn worth of antiquities have been smuggled abroad following the 2011 revolution.

The Egyptian Ministry of State for Antiquities’ Repatriation Department strives to find and bring back stolen cultural heritage in coordination with police, other ministries, and with the cooperation of international partners.

Abdel Gawad outlined the working methods adopted by the department. With the help of the Foreign Ministry, diplomatic channels are first used with the auction house where the missing object is located. If that fails, negotiations are attempted with the auction house. If this fails, legal measures are taken to stop the sale of the object on display and withdraw it from the auction hall or websites like eBay. After proving its ownership and verifying the export certificate is not legitimate, the Antiquities Ministry takes steps to have the artefact returned to Egypt.

The ministry is currently updating its database of missing objects to monitor the circulation of looted items and trace where they are found in order to have them repatriated. This is done with the help of the Egyptian police and Interpol.

Through the Ministry of International Cooperation, bilateral protocols with other countries also help retrieve antiquities and bring them back.

As part of the agreement between Egypt and France to halt illegal trafficking of artefacts, the security attaché at the French embassy in Cairo works in liaison with The Central Office for the Fight against Trafficking of Cultural Property (OCBC). La Monica identifies and shares critical information between Egyptian and French sides to facilitate judiciary procedures, and enable the relevant authorities to investigate and deal with the theft and/or receipt of stolen cultural property.

A vital tool used is the OCBC’s Treima database (an electronic search and fine-art images thesaurus). It stores photographs of art objects reported missing, or stolen in France as well as abroad.

"Our job is to ensure that stolen antiquities are found and returned to the country to which they naturally belong. It’s a right for Egyptians to get back what is part of their cultural heritage," La Monica noted.

With the support of international authorities and concerned partners, Egypt has successfully repatriated more than 7,000 artefacts from abroad since the Repatriation Department’s establishment; and over 1,065 since 2011 according to the supervisor-general of the department.

There are many examples of ancient pieces that have been recovered from a number of countries including the US, France, Germany, Jordan, UK, Belgium, Australia, Mexico and Israel.

Among recent recovery missions, Egyptian and US authorities agreed on the return of four stolen Pharaonic artefacts consisting of two coffins, a linen shroud from a mummy, and the hand of a mummy.

However there are major obstacles to retrieving many of the stolen items.

An antiquities inspector spoken to by MEE spoke of his frustration at the limited role inspectors play in rooting out crime in the field. Should an inspector come upon someone digging illegally for Pharaonic artifacts, for example, he cannot give a ticket or a citation. He is only supposed to call the police. But once they are involved, there is no arrest and the law is so “full of loopholes,” the inspector said, that even an average lawyer can get a client off.

Sally Soliman, a cultural and heritage activist, told MEE’s Amr Khalifa that using satellite data, scientists at the University of Alabama found that looting more than doubled between 2009 and 2010 and then doubled again after the revolution. "Tens of monuments were being looted," Soliman said.

Some of the stolen items went to Europe and the US, but much of the Islamic art has found its way to the neighbouring Gulf region. A lion’s share winds up in private collections in Saudia Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. But without hard facts on this, Egypt cannot hope to retrieve the treasure trafficked under radar to their new private owners.

Sabah Abdel Razek, director-general of the Egyptian Museum, is still determined to raise awareness of the illicit trade. "We hold annual ceremonies to temporarily exhibit objects either confiscated in Egypt or repatriated from abroad. We want to show these antiquities, explain how they were seized and then returned, to encourage the public to share the importance of preserving our heritage," he said.

The Egyptian Museum is also hosting a temporary exhibition from the end of October that will display a portion of objects that have been confiscated at Egypt’s border crossings and so saved from transnational smuggling.

"We will display more than 200 objects such as statues, coins, coffins and others traced back to Pharaonic, Islamic, Coptic and Greek-Roman periods,” said Razek proudly.

The battle continues.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.