'Only the voice remains': Long-censored Iranian poet takes flight online

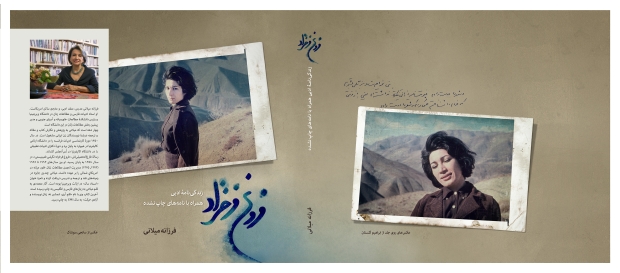

In a new biography, Professor Farzaneh Milani tells the untold story of the short but prolific life of legendary Iranian poet Forugh Farrokhzad (1934-1967). Since her death half a century ago her status has since risen to what the author calls “the Iranian equivalent of a rock star,” in a country with one of the richest poetic traditions in the world.

The book, originally in Persian and to be translated into English later this year, will be released online for free in Iran in order to ensure that everyone who wishes to read about the life of the poet will be able to do so, uncensored.

Milani, who migrated to the United States in December 1967, first dreamed of writing about the poet 40 years ago when she was working towards her PhD at the University of California Los Angeles.

Shortly before the 1979 revolution, she went to Iran, but her interview requests were met with silence and even disdain, as some wondered why anyone would want to write about a woman who had not even obtained her high-school diploma.

After the revolution, Farrokhzad's poetry was strictly forbidden and continued to be banned by the government for more than 10 years.

Later, some of her poems would be allowed publication, but many extracts remain censored, thus mutilating the art of this pioneering woman's life.

The PhD student ultimately abandoned the project and instead wrote her dissertation on a feminist analysis of Farrokhzad’s poetry. However, she never gave up hope of one day completing the biography of a poet whose focus on the intimacy and passion of a woman's life were considered to be too scandalous to be shared.

In addition to being a renowned poet, Farrokhzad was a documentary filmmaker whose 1963 film, The House Is Black, won awards at the Oberhausen Film Festival for its powerful work on a leper colony - a haunting, beautiful and humanising story told in just under 22 minutes.

40-year-old dream come true

Milani remembers a summer day in Iran at her parents’ home, filled with the scent of jasmine, when suddenly, across the garden she saw images from Farrokhzad’s film on the television screen. The young teenager at the time was stunned.

“I saw that Farrokhzad had done something unique, that she had endowed these people with amazing humanity, focusing on their resilience, their will to live and survive their medical conundrum while creating a work of art,” reflects Milani.

As a young woman, Milani always loved words and poetry, but attended dental school before switching to literature once her family arrived in the United States. “Any dentist can be a poet,” her father always said, “but a poet cannot necessarily be a doctor or a dentist.”

She recalled that as an immigrant, Farrokhzad’s poetry “became my portable home, my surrogate homeland, my evergreen garden”.

Farrokhzad’s poetry 'became my portable home, my surrogate homeland, my evergreen garden'

To Milani, Farrokhzad’s poetry is enduring not only because of its beauty, but also because she believed in risky ideals and bold dreams, knowing but not fearing consequences. She was an unyielding rebel, relentlessly exploring new domains and refusing erasure and exclusion. Perhaps this is part of the reason why Professor Milani has been able to conduct more than 70 interviews that made her 40-year-old dream a reality.

The interviews include conversations with friends, family and neighbours who knew Farrokhzad, as well as some of Iran’s foremost writers, cinematographers and painters who were close to or acquainted with the poet.

'Iranian Icarus'

Perhaps none is more revealing than the author’s interview with Ebrahim Golestan, one of Iran’s most acclaimed writers and the father of Iranian New Wave cinema who had a passionate love affair with Farrokhzad during the last eight years of her life. Golestan, who until now has been silent about the affair, granted Milani several days’ worth of interviews.

Milani is certain that Golestan was the inspiration for many of Farrokhzad’s love poems, including Conquest of the Garden, which gives voice to the woman in a story of two lovers who overcome a wall to be together.

Milani is also publishing some 30 hitherto unpublished letters, to be made available fully uncensored. In the past, letters to and from Farrokhzad have not been allowed to be published within Iran without censorship. Of the 80 letters that have been made available to the public, significant sections have been struck out.

According to Milani, the letters provide new insight into the forces driving Farrokhzad’s poetry. “This was a woman who believed it was her duty to tell the truth. What I love and admire in her, however, is that she went further - she always fought for the right to hear the truth. That same candour, that same desire to tell the truth as she saw it, can be witnessed in the letters,” Milani explained.

The author has referred to the poet as the “Iranian Icarus,” because Farrokhzad was a risk taker, always seeking freedom: “freedom of expression, freedom to own her body, her desires, her voice. Like Icarus, she wanted to meet with the sun, and she did that.” Imagery of the sun appears 77 times in Farrokhzad’s poetry. One of her most frequently quoted lines reads: “Remember flight, the bird is mortal.”

Avoiding censorship and free online access

The literary biography will be published in the United States in order to avoid censorship of any of Milani’s interviews or the poet’s letters. It will, however, be made available online for free so that readers in Iran may visit the website and access a copy.

Without adequate copyright laws between the United States and Iran, there is a risk that some publishers and bookstores will take advantage of the book’s online edition and make a profit.

However, Milani emphasised that the importance of the story must be prioritised and made accessible to the Persian-speaking world.

More than half of Iran’s population of 80 million people is under 30-years-old, and about 65 percent of homes have broadband access. The country has the highest rate of mobile use in the region, with 83.2 million mobile subscriptions. Milani is confident that readers in Iran who are interested in Farrokhzad’s life will find access to the text once it is shared online, despite censorship laws.

It would seem that once again, Farrokhzad is challenging a wall. Like her poem, Conquest of the Garden, this new literary biography will subvert censorship and a story that until now was cloaked for the most part in silence. The author explains that Farrokhzad recognised a total lack of walls was an impossibility, and that full transparency is an illusion.

Still, she continued to believe in the futility of building ever higher walls. History proves her right. Indeed, she managed to trespass walls of the visible and invisible variety.

“She gave voice to those who were silenced, she sang women’s desires, she put the female body at the centre of her poems, she took the hands of her mesmerised readers and led them into a space that was, for the most part, inaccessible - the inner sanctum of a house, the inner space of a woman’s mind and heart,” the author observed.

Transcending barriers

Walls do not only keep people and ideas out, but also in. They lead to stereotypes and misunderstandings of cultures and the people who live them. When the book is released in English later this year, it will offer a narrative of an Iranian woman that is quite different from the one that Western politicians and some media outlets tend to espouse.

Farrokhzad’s life and poetry radically challenge assumptions about how Iranian women - and indeed, all women - interact with the public and private spheres. Her words and perceptive approach to humanity transcend the barriers that audiences in both the Middle East and the West tend to apply to women of any culture.

As Milani notes, “Forugh Farrokhzad’s life and poetry frees us from the perils of a single story,” the dangers of which Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, author of Half of a Yellow Sun and Americanah, discussed in a 2009 TED Talk which now has more than 11 million views.

Women from all countries have, for centuries, been providing counter-narratives and diverse stories through the power of art, rendering dominant discourse but one story in a world of diverse experiences.

Farrokhzad was a poet who sought freedom - without fear of its responsibility. She, as the late Iranian poet Simin Behbahani reflected to Milani in an interview, “was running all the time. And the interesting thing is that she continues to run even after her death".

Farzaneh Milani is hopeful that she will one day publish in Iran without fear of censorship. For now, technology is helping to bring down the wall that separated Forugh Farrokhzad: A Literary Biography with Unpublished Letters from her readers.

The author, whose last book was called Words, Not Swords: Iranian Women Writers and the Freedom of Movement, states that while politicians come and go, literature endures. To quote Forugh Farrokhzad, “It’s only the voice that remains.”

Forugh Farrokhzad: A Literary Biography With Unpublished Letters is due to be published online in Persian later this year.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.