The phone call that says we made it to Europe alive

Ghias Aljundi fled Syria in 1998 after four years of imprisonment and torture at the hands of the Assad government. In October 2015, he travelled to Greece to help some of the thousands of refugees arriving on the shores of Lesbos. One day, he discovered a mobile phone ringing on the beach.

I had only planned to spend a week on the Greek island of Lesbos. I ended up staying three times as long, spending most of my time out in the water, welcoming boats to shore and helping unload packed dinghies. I couldn’t continue seeing the images that were being broadcast on TV without wanting to act.

After a tiring and nerve-wracking journey, the new arrivals needed a warm welcome and reassurance that the Greek authorities would not return them to Turkey. But no matter how terrifying the journey had been, most refugees spent their first moments searching for a way to tell loved ones at the other end that they had arrived safely.

Families travelling together would gather around one phone on the beach to Skype relatives back home. We heard them laughing, cheering and crying with happiness. We could hear both sides: mothers praying for their children to arrive safely and children asking their parents to pray for them.

Many people have no phones or reception when they arrive, and they ask to borrow a mobile from one of the volunteers. One day, a refugee woman with two small children made a call from my mobile but got no answer. Before the young family was transported to the camp, I took a few photos of them. Later I received a call from the woman’s father and explained that they were safe. I sent him the pictures and he wrote back, saying: “Now I feel happy seeing that my smiling grandchildren have arrived”.

There were many such occasions where being able to communicate made a huge difference. Most of the camps in Greece and many sympathetic local cafe owners offer free Wi-Fi so refugees can contact their families and friends. They understand how vital it is for refugees to communicate with their families. I would sometimes stay with family members minute by minute via phone or Facebook while their loved ones arrived by boat.

I could see how important it was to try and help them stay calm. For me, the feeling of anxiety was the same - when the boats arrived safely, I would have the same feelings of relief.

On the other end was a woman. She didn’t have time to find out that I wasn’t the person she was trying to reach.

“Where are you, my heart?” I heard her say. “Have you arrived safely?”

When I told her who I was, she started to cry, thinking something terrible had happened to her son. The family, I learned, were from Darayya, a suburb of Damascus that was a stronghold of opposition to President Assad in the early days of the revolution and has since been flattened by government forces.

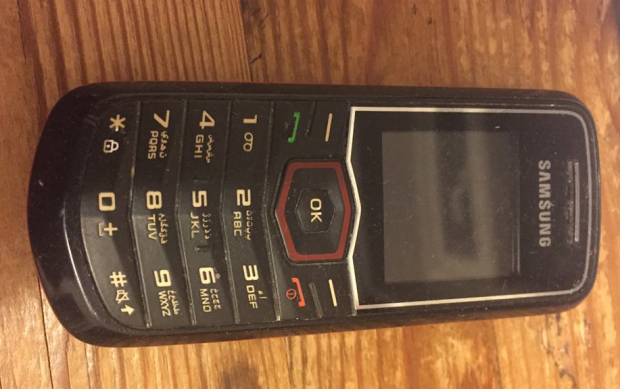

Then she gave me her son's name, but it was impossible to find him at the busy camp. After two days of searching, I found him on Facebook and gave him the numbers he needed from his mobile. I called the mother again – she was happy, reassured her son was safe. I still have that phone in my house, and her voice still sticks in my mind.

These incidents and countless other similar ones show that the families of refugees deserve attention too. The dinghy journey is always accompanied by a journey of anxiety and waiting for the families on the other side of the sea. Refugees wait desperately to arrive on the land and their families wait to hear their voices to know they have arrived safely. The boat journey is longer than the several miles crossed in the dinghy; it’s a journey from the heart of their families to their final destination.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.