IN PICTURES: Armenian silversmith heritage survives in Turkey's Van

VAN, Turkey - Metin Bicini's father, Ismail, opened a small silver store on Marasht Street in the city of Van in eastern Turkey 41 years ago.

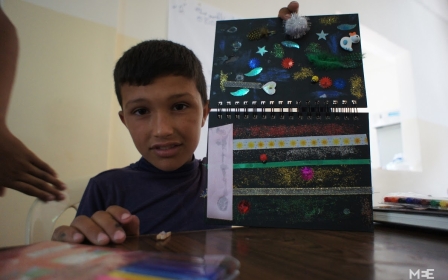

In a small room above the shop, Ismail teaches his young sons a craft that was secretly handed down to him by a small Armenian community that continued to live in the city despite mass expulsions of Christian Armenians from Turkey during World War I. Acts that many believe amounted to genocide.

“It's important to teach silversmiths when they are young, so they can develop an eye and touch for the delicate work,” Bicini said.

Today, the original store is run by Bicini and his family, who also have two other shops in Van and a workshop outside the city that employs 12 local staff. The techniques haves been transferred to the younger generation through years of training and practice.

Bicini says his father was a Turk who had many Armenian friends, but people’s roots in this part of Turkey are hard to trace. Some are Turks, but there are also many Kurds. If any are Armenian, they tend to be private about their identity.

“We watch our workers and develop their skills. Not everyone can do it; we only select the best,” Bicini told Middle East Eye.

The workshop produces pieces that are sold in local stores. The delicate silver jewellery is inspired by the Urartu period – a kingdom that existed in parts of what is modern-day east Turkey during Biblical times. However, they also include traditional techniques used by the Armenian silver makers in the region before the expulsions.

Bicini says that his most popular pieces are Urartu necklaces, made out of granule silver, of the style which were worn by ancient kings. To construct these pieces, silver is melted into tiny balls and delicately inlayed and composed into Urartu symbols and motifs. The work is incredibly intricate and requires a lot of attention and time, which is why this jewellery was reserved for royalty.

Other popular pieces are from designs worn by non-royals, known as hammered silver. The store also sells traditional rings, bracelets, trinkets and cuffs.

“You can't find these pieces anywhere else, they're so local to Van and the Armenians who lived here,” Bicini said.

The family still keeps a secret recipe for making Armenian Sawat (black), which is a complex mix of copper, silver, tin and sulphur.

Traditionally, the Armenians would engrave silver pieces (vases, dishes, jewellery, cups, dagger holders, belts) and coat them in sawat. The sawat would seep into the engravings and set. The piece was then polished to expose the design.

Before the mass expulsion of Armenians from Turkey in 1915, there were more than 120 Armenian gold and silver workshops and a 70-strong association of silver and goldmakers in the old city of Van. They were concentrated in the Shahestan Bazaar and locals admired and respected their great craftsmanship.

However, as the Ottoman Empire began to suffer setbacks during WWI, the authorities started to blame the Armenians, forcibly pushing them into what is now modern-day Syria. According to Armenian historians, 1.5 million people died, although Turkey says the numbers are much smaller and strongly denies that a genocide took place. Homes, shops and whole towns and village were abandoned. Many did not even have time to close their shops in Van’s bazaar.

Bicini says that over the years he has found many antiquities that Armenians buried before evacuating the city. Local farmers sometimes uncover them while ploughing their fields, and give them to Bicini and his family for safe keeping.

“Many of these pieces inspire us to create new designs,” explained Metin.

While ideally these would be placed in a museum in Van, ongoing sensitivities over the events of 1915 makes this unlikely in the near future.

Bicini and his family hope to open a new shop in Istanbul soon, but he remains committed to supporting local artisans in Van and the wider community. He also hopes that one day a museum will be built to honour the local Armenian heritage, although he doubts the authorities would agree to such a plan.

“The political situation is not easy, there is a lot of meddling of news to keep people from visiting us. When there are no tourists, it's hard to make a profit,” he said. “Most Kurdish people like to buy gold, not silver.”

Instead, buyers from other Turkish regions, Armenia, Iran and the West are their main customers.

“People who understand and know Armenian art and culture like to buy our pieces,” he added.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.