Tunisia: When your home turns into a prison

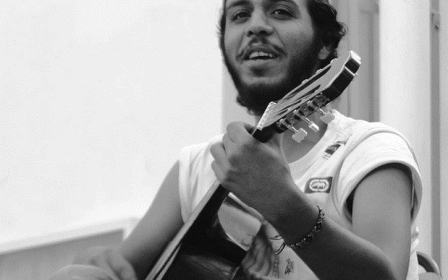

TUNIS - Nizar Dabbachi, 38, lives in an upscale neighbourhood of Tunis, where newly built houses and marble details distinguish it from the average Tunisian district. Yet for Dabbachi, his home has become his prison, and the only thing keeping him connected to life outside his walls is his big flat-screen TV.

In November 2015, Dabbachi was placed under house arrest and his world shrank to a 2km radius from the police station that he must report to every fortnight and the nearby mosque, where he goes to pray. Before his ordeal began, Nizar earned a living selling mobile phones and later body-building supplements. But since his detention, he has not been able to work and his home has gone from a place of comfort to a prison cell.

Illegal detentions

“I left the mosque and the police said, come with us, and asked me about my residential status and gave me a paper and asked for a signature,” Dabbachi said, explaining how he was put under house arrest.

“I asked for a copy and they said ‘no it is forbidden’. They haven't given me any document, they explained nothing,” he added, stressing that he had no idea why they arrested him.

Mouna Elkekhia, North Africa researcher for Amnesty International and author of the recent report on human rights abuses in Tunisia, “We Want to End the Fear,” said that those that are detained do not usually get legal documents stating why they are under house arrest.

“Without that it is very hard to take it to court and challenge its legality,” Elkekhia said.

“They don’t know how long house arrest will go on for; the police will tell them until the state of emergency ends,” she added.

Maitre Rafik Ghak, a lawyer working for the Observatory of Rights and Freedoms of Tunisia (ODL) agreed, saying that it is illegal to put people under house arrest indefinitely. Legally, someone can be placed under house arrest for one month. Then it can be extended for four months but beyond that it is illegal, according to a presidential decree of 1978.

However, many complain that they have been under house arrest for much longer than four months.

Unseen 'evidence'

Dabbachi was arrested before and placed in prison for six months in April 2013. He said that police beat him and he was never properly advised on why he was arrested.

According to Dabbachi, when his house was searched at the time, the security official said that “they [had] found a book about self-defence on my computer and a religious book from my mosque in my house".

When the case was presented in court later on, a judge dismissed the case stating no reason for the initial arrest.

'Once a person is inscribed on a list of suspected terrorists, the police will always regard them as a terrorist, even if judge says this person is innocent'

- Maitre Rafik Ghak, rights lawyer with ODL

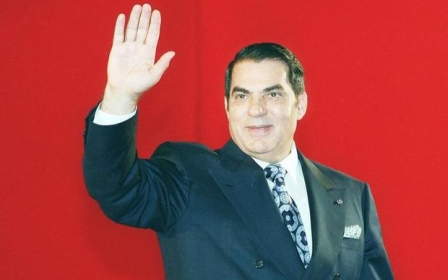

Elkekhia said that Dabbachi had told her that he was previously imprisoned under ousted President Ben Ali after attending the wedding of a man who security officers later claimed was a “terrorist” suspect.

Dabbachi is unable to afford legal representation and believes that the dossier which is still being held at his local police station is still haunting him.

“That could very well be the reason he’s under assigned residence order now,” Ghak said. “Once a person is inscribed on a list of suspected terrorists, the police will always regard them as a terrorist, even if a judge says this person is innocent,” she explained.

Denied surgery

Adding to his problems is the fact that Dabbachi needs surgery to remove a metal plate from his knee - a result of a previous motorbike accident. Yet the hospital where he should receive treatment is 30km away and he is not permitted to travel. And without work, he is unable to afford the surgery or the legal representation that could help him gain permission to get medical help.

The young man is in constant pain and feels older than his years. “I’m 38 years old, but I’m like an old man,” Dabbachi said.

'I’m 38 years old, but I’m like an old man'

- Nizar Dabbachi, under house arrest

For people in similar predicaments, restrictions on movement to access medical care is a common problem, according to Ghak. He cited the case of a 34-year-old disabled man with multiple health issues that he is representing. “He has to apply for permission every time he needs to visit the hospital,” he said.

According to the law, authorities must provide "for the livelihood of the person [placed under house arrest] and his family.” But Dabbachi, who lives with his parents, said that he was surprised to hear that he was entitled to any payment from the government.

“I have not received any payment from the government - not one cent," he said,

State of emergency

In 2015, the Tunisian national dialogue quartet won the Nobel Prize for Peace for transforming Tunisia into a widely proclaimed beacon of democracy in the Arab world. Yet just six years after the revolution, Tunisia is now coming under scrutiny for its failures to respect human rights and its wide abuse of using house arrest as a means of control.

Tunisia has been under a state of emergency for the past six years with only an 18 month break starting in 2014. In July 2015, it was reinstated following the much publicised attack in Sousse by a lone gun-man which resulted in the deaths of 38 tourists.

House arrest is just one of several blunt tools used by security forces to allegedly deal with home-grown terrorism. Governed by article five of the presidential decree of 1978, a state of emergency gives the government wide-ranging powers that include imposing curfews and house arrest.

Marwen Jedda, executive director of the ODL said that the government prefers this type of procedure in order to monitor suspects closely.

The 1978 decree states that house arrest may be used for anyone whose “activities are deemed to endanger security or public order”.

On 28 November 2015, the Interior Ministry said in a statement that those placed under house arrest were either people who returned from conflict zones or are suspected of having links to militant groups such as Ansar al-Sharia.

Under review

The effects of house arrest go beyond having consequences for the arrestee: entire families are subject to extremely stressful interrogations. Amnesty International's report is filled with disturbing stories of night raids and questioning of families and wives of the detained. Reports indicate that expecting mothers who were interrogated have even miscarried due to the emotional duress.

Elkekhia said that many of the people she interviewed for the Amnesty report described human rights abuses similar to those reported under Ben Ali.

“We interviewed people who had been subject to these nighttime home raids with security officers who were fully armed in masks and were terrorising people in the houses,” she said.

Human Rights Minister Mehdi Ben Gharbia responded to the report saying that "All violations mentioned in the report [of] Amnesty are individual violations [and] are being investigated. We cannot accept these kind of violations in the new Tunisia,” Reuters reported in February.

This contradicts an earlier statement given to Amna Guellali, Tunisia director of Human Rights Watch, which justifies the use of house arrest. “The minister said that ‘these measures are warranted by the state of emergency, that they are of exceptional nature, taken against people who represent a threat to security’," she said.

Human rights experts say that they law is being reviewed, but there are no details on what kind of amendments will take place. UN special rapporteur on human rights and counterterrorism, Ben Emmerson, said in February during a visit to Tunisia that he was sure that the House arrest law would be reviewed, as Tunisia undergoes the UN Universal Periodic Review.

“I think the review is still at a preliminary stage. I have not seen any draft,” Guellali confirmed.

Haunted by the past

Like other house arrestees, Dabbachi's family and friends are also under threat of intimidation and are being questioned or have been arrested by the police for their links to Dabbachi.

“I get the impression that my friends are afraid of the police. They took one of my friends because he had a drink of coffee with me,” he said.

He now feels that people are avoiding him as friends make excuses not to have coffee with him and people at the mosque “just say 'hello' and that’s it”.

There are also larger fears about the safety of his parents looming in the back of his mind. “They are frightened all day; they are frightened of being taken to the police,” he added.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.