Turkish Aegean island grapples with threats to its wine industry

BOZCAADA, Turkey - A group of young artists in stained coveralls stand in a stone-walled square. They are splattering a three-by-three-metre canvas with paint from overflowing wine glasses, then smearing it with their hands across the cloth. “Don’t feel bad; The grapes are still growing in the vineyards, Despite the wine ban,” reads an elegantly bespectacled gentleman standing to one side.

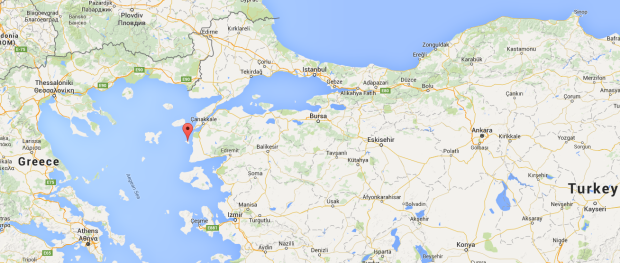

The grapes are those of the Turkish island of Bozcaada, or Tenedos by its Greek name. On the map it seems an unassumingly small landmass plopped in the northeastern corner of the Aegean Sea that laps both Turkey and Greece, with the island of Lesbos to the south and the visible ruins of Homer’s ancient Troy on the eastern shore.

It is a 40sq km windswept piece of land with stunning shores, fertile soil, and aromatic breezes laced with wild thyme and salt, and a three-millennia history that levitates between myth and truth. Also an attractive enclave and retreat, Istanbul’s and Ankara’s middle-upper echelons, generally of a liberal tilt, gravitate to its compact village, unspoiled shores, outstanding food and selection of wines particular to Bozcaada.

Now these grapes and wines that power much of this small island’s economy have also become local protagonists in the country’s larger struggle to stave off a conservative march on the progressive and secular swathes of society.

Author and journalist Haluk Sahin, who organises many of the island’s cultural events such as an annual Homer reading in 22 languages at his wife's art gallery, first went to Bozcaada in 1988 on assignment for a commissioned article.

“When we came to the island it was not well-known at all. It was one of the two Aegean islands that belonged to Turkey, and few people knew the difference between Bozcaada (Tenedos) and nearby Gokceada (Imroz)”, he told MEE.

Today there are regular connections to the mainland and even a smattering of international tourism, but up until 1992 “foreigners could visit Bozcaada only after obtaining a permit from the Canakkale provincial governor (Vali),” said Sahin.

“Two retired military landing-crafts, used in Normandy and given to the Turkish navy, were converted to ferry boats and served as the lifeline to the Anatolian mainland. It was quite distant,” he added.

Though never an even split between Turks and Greeks, the island’s population throughout history was made up of both ethnicities in varying numbers and it still has a distinguishable Greek flair unique to that part of Anatolia. By the time Sahin began frequenting the island, “the number of Greeks had declined to maybe 100 or so,” he reflects.

“The big exodus had started in 1955 after the attack on the Greek neighbourhoods in Istanbul. It continued until the end of the 1990s due to the crosswinds of nationalism on both shores. Many emigrated to Australia after selling their property here.”

Yet the island’s Greek inhabitants were spared from the forced population exchange that began in accordance with the Lausanne Treaty in 1923. The population exchange lasted four gruelling years as the Ottoman Empire was replaced by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s republic.

“The Turks of Crete, Rhodes and Lesbos came to Turkey, but the Rum of the two islands (Tenedos and Imroz) stayed behind. The Greek-speaking people of Anatolia and the Aegean were called Rum, or Romans, as they were the remnants of the Eastern Roman Empire. We still call them Rum,” Sahin said.

Island of wine

Today, many of the island's inhabitants think it represents a keyhole into Turkey’s liberal thinkers and dissident voices from all fields and practices.

“Turks living on the Aegean and Mediterranean shores have been voting for the liberal parties on the left for some time, particularly the CHP (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi - Republican People Party), a party defending Ataturk's secularist ideas and Western lifestyle,” said Sahin, who once risked jail time for articles considered "anti-government".

“Canakkale, the provincial capital, has had a CHP mayor for the past several elections. But of course the Istanbul escapees also tend to be leftist, lifestyle liberals. In the last election, the AKP (governing Justice and Development Party) was outvoted 2 to 1 by the CHP."

The island’s viticulture-based economy is gradually shifting to a tourism-based economy. “When we came to the island about a quarter of a century ago the annual calendar was a reflection of what was happening in the vineyards. Now it is mostly about summer holidays, along with national and religious festivals. The grape and wine production figures are down substantially compared to 90, 50, even 25 years ago,” added Sahin.

This small island’s preeminent wine-producing tradition still has enormous potential for future growth. With its four native varietals - Kuntra, Karalahna, Cavus and Vasilaki - it is home to four important vineyards, including one of the longest standing wine-producing families in Turkey, Camlibag, run by Hasim Yunatci, the founder’s great-great grandson.

Wine export blocked

But another effect of regulations put in place by the current government also means that centuries-famous Bozcaada wines are no longer readily available throughout Turkey.

“Now the cargo firms cannot accept alcoholic drinks. Before all the vineyards were sending all over Turkey,” another of the island’s residents, Umit Hamlacibasi, told MEE.

“And whereas three years ago, until the summer of 2012, visitors could be given samples, now they have to either buy blindly or purchase a glass at an authorised tasting room,” added Hamlacibasi, who also authored a cookbook celebrating the Greek-Turkish tradition on the island.

“The good thing now is that all the vineyards found a loophole for the tasting. Now finally they all have their little cafes that are certified by the local offices (municipality, governor, health and agriculture offices),” she said. "So it looks like the problem is solved, at least until another restriction comes up.”

One of the islands most modern wine producers, Resit Soley, designed an amusing, and provocative, label for his Housewine blended from indigenous island grapes. The founder of Corvus Vineyards, named after the island’s small, blue-eyed and raucous crow, slapped a yellow measuring tape on the front of the bottle as a way of poking fun, asking if the government wants to count every drop imbibed.

“Alcohol publicity and advertising restrictions have definitely had an effect. The wine companies cannot sponsor cultural events, offer wine-tasting visits, organise fairs. Turkey never had such restrictions ever since it became a secular republic in 1923. Furthermore, taxes on alcoholic beverages are extremely high, as are prices,” said Sahin.

As a veteran journalist, TV and newspaper columnist, Sahin has spent over 40 years covering the complexities of Turkish society, along with the past and present events that continue to shape the country. Now an emeritus professor at Istanbul's Bilgi University, Sahin is working on his 27th book, this one on Turkish-Armenian relations. “My toughest,” he said.

Bozcaada as metaphor

Sahin’s adoration for the island is infectious as he wipes the dust off the pages of its history and brings it to life through his poetry and eloquent presentations. Often Bozcaada becomes a metaphor.

Just as diversified groups from all walks of Turkish society joined arms and marched down Istanbul’s Taksim over the threatened destruction of Gezi Park in 2013, the long arm of the country’s conservative government has united islanders and adopted residents, disdainful of interference.

“Over the last decades, the island has always been very pro-Republican, i.e. lovers of Ataturk, and his progressive Turkey. Not nationalist, however,” says Sahin. “The recently-elected mayor is from the party of Turkey’s modern founding father, Ataturk, the Republican People's Party CHP, a Kemalist and social-democratic political coalition.”

Bozcaada is inextricably linked to the ancient history of Troy that looms on the opposite shore. In his 2004 book Were The Trojans Turks?, written when the blockbuster film by the same name was released, Sahin said he “developed the argument that even though the Turks may not be Trojans in an ethnic sense they find themselves on the dividing line of Europe and Asia, East and West just like Trojans of yore”. A situation that he said was fraught with opportunities and dangers.

Just as the island’s ancient history pulsates continuously through the veins of time, one of the island’s perpetual visitors, the wind known as Poyraz, continues to hold symbolic meaning. “Poyraz, the north-eastern wind, was the source of the gold of Troy, and hence of the island. Ships sailing upwards toward Istanbul and the Black Sea waited, sometimes for weeks, for a change in the wind. They didn’t have the technology to move upstream otherwise,” Sahin explains. “I have called it the ‘effendi’ or lord of the island.”

“Poyraz constantly reminds one that they are alive,” he said. “And that if something is wrong, this too shall pass, blown by the winds of time.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.