Introducing President Biram of Mauritania

There is more to Mauritania’s Presidential election than meets the eye. Mauritanians go to the polls today, 21 June, to elect a new President. Or, at least, some of them do, as not all are on the electoral roll and most of the opposition parties are boycotting what they call an “electoral masquerade”, as they did in the legislative elections last November, and for the same reason: that Mauritania’s elections under President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz are neither free, fair nor transparent. There will be “irregularities”.

The result is therefore a foregone conclusion: incumbent President Abdel Aziz will win, probably overwhelmingly, against four other candidates. The fact that a significant proportion of Mauritania’s population will not have participated will not bother him unduly. He is not a great fan of democracy.

A former army general, Abdel Aziz played a key role in two military coups that toppled elected Presidents Maaouya Ould Sid'Ahmed Taya and Sidi Ould Cheikh Abdallahi in 2005 and 2008 respectively. Then, after seizing power in 2008, he wrapped himself in the blanket of the Union for the Republic (UPR), a political party which he formed, resigned as Army chief and had himself elected President in 2009. Like a number of other military-backed, dictatorial leaders in the MENA region, he is backed by the West, notably France and the US, whose geo-political and “counter-terrorism” interests he serves well.

While the boycott will not affect the election’s outcome, it will affect the turnout figure. Abdel Aziz wants the turnout to be as high as possible to show that the boycott was ineffectual. The boycott will certainly have some impact in the major cities, such as Nouakchott and Nouadhibou, but much less so in the rural areas where tribal values are strong and ties with the government are not easily broken. But the President is clearly worried. He has already come up with an explanation for a low turnout, saying the opposition has been buying identity cards “on a grand scale to influence the participation rate".

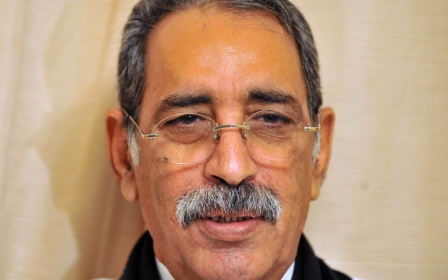

Abdel Aziz’s main challenger, and by far the most interesting, is Biram Dah Abeid. Dah Abeid (or simply Biram as he is often known) is Black and of ex-slave origin. He is the President of the Initiative for the Resurgence of the Abolitionist Movement (IRA), assisting slaves and former slaves in obtaining legal representation, advocacy and survival. In 2013, he won the prestigious UN Human Rights Award.

Mauritania’s demography, especially in terms of both ethnicity and slavery, is highly complex and problematic.

Traditional Mauritanian society was categorised very crudely into “white” Moors (Beidane) of Arab-Berber origin; “black” Moors of slave or ex-slave origin, and various black communities (Toucouleurs/Tukulors, Peuls, Soninke/Sarakole, Wolofs, etc.). “Black” Moors are known as “Harratin”, a term which has different meanings in other Saharan-Sahelian countries. They comprise an estimated 30-40 percent of Mauritanian society; “white” Moors possibly a fraction less, and Black communities around 20-30 percent. In other words, not only are Harratin probably the largest single ethnic group, but, if reduced to racial categories (i.e. "negroid origin” and “white” - Arab-Berber origin), “blacks” outnumber “whites” approximately 60-40.

In a country in which these racist-ethnic categories are socially almost all-determinant and where slavery, although abolished in 1981 and criminalised in 2007, is still a major and very real issue (The US State Department estimates that 20 percent of Mauritanian’s population is enslaved), with “slave practices” still continuing and deeply ingrained in many mind-sets, such racist-ethnic statistics are politically important.

They mean, for instance, that if all Harratin and blacks were registered on the voters roll, which they are not, and if Mauritanian elections were 100 percent free and fair, which they are not, and if all Harratin-blacks voted on racist-ethnic lines, which is conceivable, then Biram Dah Abeid would be President.

Let me introduce President Biram of Mauritania. What an idea! What a future!

What percentage of the vote will Biram get? It could be the election’s most interesting statistic. If he gets around 10 percent, then the polls have certainly been rigged. If above, say, 20 percent, then it is a sign that social and political transformation could be in the offing next time around.

However, there is more to Mauritania’s election than such tantalizingly interesting possibilities. The election is central to Algeria’s latest ploy in the long-running Algerian-Moroccan conflict, which is essentially over the Western Sahara.

Since Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika raised the Human Rights issue last October, the tit-for-tat battle has swung back and forth on an almost weekly basis. In April, Morocco infuriated Algeria by announcing that it was holding a forum in Fez next year, under the auspices of King Mohamed VI, to celebrate the bicentennial anniversary of Sheikh Ahmed Tidjani (1737–1815), the founder of the influential sufi Tidjaniya Brotherhood (zawiya).

This is like hitting Algeria ‘below the belt’, as the Sheikh’s home was Ain Madhi, near Laghouat in Algeria, which is now the effective HQ of the brotherhood and a place of pilgrimage for its members, who are extensive in the Sahel. Holding such a ceremony in Fez is an ingenious move by Morocco. It is an attempt to use King Mohamed VI’s religious prestige to draw Tidjaniya members towards Morocco and so weaken Algeria’s influence in the Sahel.

However, Mauritania’s election has provided Algeria’s Bouteflika with an opportunity to strike back. Algeria’s tactic has been to (co-)finance Abdel Aziz’s election campaign and to deliver him the votes of some 6,000–8,000 Sahrawis of Mauritanian origin living in the Polisario-run Tindouf refugee camps in western Algeria.

In May, Bouteflika’s Foreign minister, Ramtane Lamamra travelled to Mauritania and is accredited by opposition sources in Nouakchott to have handed over US$200 million to fund Ould Abdel Aziz’s presidential campaign. According to other sources, Algeria is notoriously generous in buying the support of other countries in its diplomatic war against Morocco. President Bouteflika is reputed in the last four years to have written off US$902 million owed by 14 African countries.

President Ould Abdel Aziz’s mother-in-law is Moroccan. Algeria’s strategy is to try and prise Mauritania away from the Moroccan sphere of influence. If a couple of hundred million dollars enables it to succeed in doing so, it will more than compensate for whatever loss of influence Algeria suffers from Morocco’s Tidjaniya games.

- Jeremy Keenan is a Professorial Research Associate at the School of Oriental and Africa Studies. He has written many books including The Dark Sahara (2009) and The Dying Sahara (2012). He acts as consultant on the Sahara and the Sahel to numerous international organisations, including the United Nations, the European Commission and many others.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo credit: Mauritania presidential candidate Biram Dah Abeid in Nouackchott, on June 19, 2014 (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].