UK legal ruling over a Bahraini prince opens the floodgates for prosecutions

The anger felt by the despots of the Middle East over what is said and written about them in London could stem for the need to protect their international image and their investments. The British based media are out of their reach and the only way they can vent their frustrations is to threaten to cancel lucrative military contracts.

But there could also be an element of fear at work. The challenge to them is a personal one and it comes not from an oppositional media or an unruly diaspora, but from an altogether different source -- the British legal system.

Those who were part of an administration with command responsibility for mass killings, who arrested and tortured their political opponents, who ordered airstrikes which wiped out whole families in Gaza have something real to think about the next time they land at Heathrow Airport. They could face arrest -- not just from private legal moves but from the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) itself.

For decades, the British government has tried to limit the risk of arrest, by offering serving members of foreign governments immunity from prosecution. It can and has been argued that legal immunity is needed to oil the wheels of diplomacy. Governments exchange intelligence. They also need to talk to each other. Little will change there.

But it is also true that this loophole has been exploited by governments for political reasons. The immunity shield can be switched off as easily as it is switched on. Look how suddenly it disappeared for Gaddafi and his sons, who had much private business to conduct in Britain and France. It has also been abused by offering members of a foreign government "special mission" status, whether they are on a special mission or not.

The law about who should benefit from this immunity, when and why, is being challenged, especially when immunity comes into conflict with larger international obligations. The UK is signatory, along with 160 other countries to the UN Convention against Torture. This includes an obligation to investigate and prosecute torture suspects if they come into your jurisdiction. Immunity violates the convention, and makes the immunity provision subject to legal challenge.

So what happens in the British courts effects not just the reputation of foreign governments, but could materially limit the freedom of movement of their ministers and officials.

As the world's attention was focused this week on the Turkish border with Syria, a significant legal development took place in London.

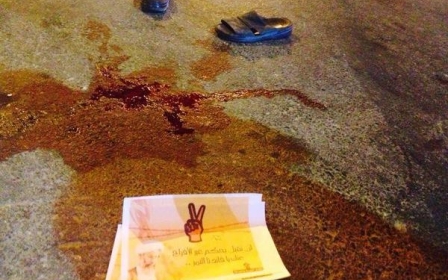

A Bahraini prince and regular visitor to Britain lost his immunity from prosecution, which the CPS claimed he had. The High Court ruled that Prince Nasser bin Hamad al-Khalifa did not have immunity against arrest and prosecution in the UK over allegations he tortured detained leaders of a pro-democracy movement.

A horseman who represented Bahrain at the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in London, Prince Nasser has been a regular visitor. Having gone through the officer training course at Sandhurst, he no doubt felt he owned the place. He probably does. But the son of the king is also accused by an anonymous appellant who was himself tortured in Bahrain, of "flogging, beating and kicking" two pro-democracy protest leaders at Manama Fort prison clinic al-Qala'a in 2011.

The Bahraini government "categorically denied" any involvement in torture by the prince, and a spokesperson called the court action "an ill-targeted, politically motivated and opportunistic attempt to misuse the British legal system". Bahrain refused to take any part in the proceedings in the High Court. That, in retrospect, may have been a mistake, which they will likely not repeat.

Whether or not the allegations against the prince stand up in a court is not, for the moment, the issue. As the prosecution said in a statement to the court “in the light of the Claimant’s intention to submit further evidence to the police (who are responsible for investigating the allegations), the Crown Prosecution Service has agreed to state to the police its view that immunity should not be a bar to any such investigation on the evidence currently available.”

The ruling does not spell the end of the immunity system, but it curtails it. The government can still offer immunity to diplomats posted to embassies or to those on a "special mission" who come for official meetings.

But it does mean that people who are alleged to have committed crimes grave enough to be prosecuted under universal jurisdiction and who travel to Britain as private individuals, now face arrest either as a result of a private petition to the courts or from the CPS themselves.

The ripples of this ruling spread well beyond Bahrain. The ruling strengthens other cases going through the British courts. Some 30 members of the Egyptian interim government and security personnel are implicated for their part in organising the Rabaa massacres in Cairo in August last year. A hearing is to be held applying for permission for a judicial review against a CPS decision that members of the Egyptian cabinet had some form of immunity. In May this year, there was sufficient doubt on this issue to force Egyptian Ministry for Industry and Trade Mounir Fakhry Abdel Nour to cancel a visit to the UK, reportedly out of fear that he might be arrested, after a hotel booking had already been made in his name.

The ruling is about the present misdeeds as much as it is about past ones. Some 82 detainees have died in custody since the crackdown was launched against all political protest in Egypt last July. According to a report by the Arab Organisation for Human Rights in the UK , 37 of these were killed when they were transferred in a van. Others died of torture or after being denied access to medical treatment. The ministers and officials responsible could face justice for these crimes in Britain.

The reports alleging these crimes are detailed for a reason. One day they could be used in evidence. The body of evidence admissible in court, with dates, witnesses and testimony, is accumulating as these reports stack up. A boost was given to this process by the Human Rights Watch report on the Raba'a massacres, which found evidence that the killings were premeditated and that the Egyptian authorities had planned for many more deaths than actually took place. Much as Egypt's current rulers may want it to, none of this evidence will disappear.

Similar evidence gathering is taking place over Israel's last attack on Gaza. Israel's Justice Minister Tzipi Livni was given temporary immunity in May this year to meet Foreign Office ministers in the UK. A British law firm acting on behalf of a relative killed during Israel's previous assault on Gaza in 2008 made attempts to secure a warrant for her arrest. But former senior Israeli security officials travel to Britain all the time. The risk they incur by doing so has just increased, if their presence is detected.

The arguments over evidence and immunity go hand in hand. The greater the weight of evidence for that crime, the harder it is to argue in court that a participant in that crime should be protected by a British government from having to answer for it. With the route to the International Criminal Court currently barred, universal jurisdiction is looking like a more effective way of securing justice.

- David Hearst is editor-in-chief of Middle East Eye. He was chief foreign leader writer of The Guardian, former Associate Foreign Editor, European Editor, Moscow Bureau Chief, European Correspondent, and Ireland Correspondent. He joined The Guardian, from The Scotsman, where he was education correspondent.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo Credit: Prince Nasser bin Hamad al-Khalifa with his father-in-law and ruler of Dubai (L) Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum and UAE President Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed al-Nahyan (R) in Dubai

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].