In conversation with Syria’s 'White Helmets'

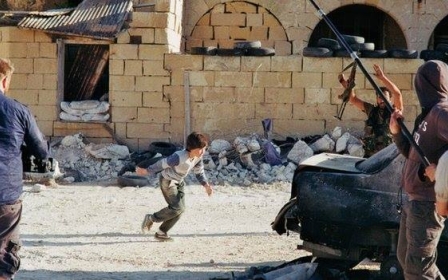

In Syria today, where the violent and protracted civil war seems to rob the country of any form of hope, a relatively small group of volunteer civil defenders has captured the hearts of many. Described by some as “real-life superheroes,” these volunteer firefighters and search and rescue workers have been working on the frontlines of the conflict, digging survivors out of the rubble of collapsed buildings and bringing some order to rescue efforts after barrel bomb attacks.

With no political leaning, the team of over 2050 works to save Syrians - opposition, but also regime supporters - from fire and crumpled stone in the aftermath of shellings and airstrikes. In the past year alone, their work has saved the lives of 10,221. We spoke to four of these volunteers via Skype, while they were on brief visits to Turkey for training, to talk about their work and the ethos of their organisation.

“On duty 24 hours a day”

“When the revolution started, I wanted to help peacefully in my community,” said Raed, a former businessman from Idlib. “I helped provide food and shelter - and with getting people to safety in Turkey.” As so often happens in conflict, the chaos of Syria’s war has seen the breakdown of public services - of schools, garbage collection, public transport and medical care. Local coordination committees and informal networks gradually emerged, taking over public service provision when and where they could. In the aftermath of bombings, ordinary men such as Raed - former teachers, painters, mechanics, bakers - began to offer their services in rescuing those trapped within the rubble. “I would go out and help pull people from collapsed buildings,” he explained, “drive them to hospital, and deliver relief services.”

With time, these everyday heroes have been unified into a single civil defence force. The scope of their work has increased, and many members have now received valuable additional search and rescue training in Turkey - led by organisations such as ARK (a stabilisation consultancy firm) and May Day Rescue.

“We are on duty 24 hours a day,” sighed Raed, who now works in the Idlib branch of the civil defence. “The bombing just doesn’t stop, and there are always people who need our help.” With reports indicating a recent escalation in the regime’s use of the crude but highly destructive barrel bomb - despite the UN Security Council demanding an end to their indiscriminate use in February 2014 - the strain on these volunteers is only increasing.

Possessing only limited rescue machinery, and lacking advanced equipment such as thermal imaging cameras, the volunteers tell us how they are often forced to dig through collapsed buildings with their hands, fearful of crude machinery further injuring those trapped within. “Sifting through rubble and dust takes time,” says Khaled, a former decorator who now volunteers with the civil defenders in Aleppo. “It’s hard in a city such as Aleppo where the buildings are tall. When one collapses, it’s a lot of floors to dig through. It’s especially hard in the old city where the streets are so narrow that much of the larger rescue machinery cannot get through. Operations there take a lot longer.”

“We lose some - but we save others”

It is not just search and rescue which is within the White Helmet’s remit. Their duties are vastly varied: they fight fires, they provide first-response medical assistance, they distribute manuals on self-protection, they clear roads to make them usable again, they teach kids about the dangers of unexploded ordinance and how best to respond to airstrikes, they build and repair water and electricity services. Simply put, they are the saviours of communities. And it is not just men. There are now 56 women who have been trained in light urban search and rescue, as well as medical response.

“Women are vitally needed,” said Mais, a soft-spoken schoolteacher who has recently undergone training to join the White Helmets. “It’s common in Syrian society that a man shouldn’t be seen touching a woman. Of course it’s never stopped a man in the civil defence performing a rescue that is needed - but it makes it easier if women like myself are there to help too.”

Working as rescuers on the front lines of this war is fraught with dangers - particularly given the regime’s tendency to strike the same site twice, often catching rescuers in its second attack. Twenty-six volunteers have been killed in the past four months alone. “Are you scared?” we asked Mais the day before she headed back into Syria to start her new role as a civil defender. “Everyone gets hurt in Syria, and if I die, then I die,” she said.

Mais’ fearlessness may perhaps be surprising given her timidity - but there simply isn’t time to dwell on the horrors of the war. Instead, for volunteers such as Raed, Khaled, and Mais, the dangers of the job serve as incentives to continue their work. “When someone dies, it makes me more passionate about my work,” said Raed. “If it’s precious enough for someone to give their life, then it’s worth my struggling on. We lose some - but we save others. So we don’t stop.”

Role models for the community

But it is not just the White Helmets’ practical importance within the conflict which makes them so valuable. It is also their role as symbols of hope for their communities. “Syrians recognise us,” commented Raed. “They stand back to let us do our work - they respect us. I remember one time when we responded to a shelling in a village in Idlib. After thirteen hours of work, we were able to pull a woman alive from the rubble, her son standing with us as we dug her out. All the villagers came into the streets to celebrate!”

With their skills and determination providing a ray of light for communities living in the war’s constant shadow and a permanent fear of death raining from the skies, the White Helmets have created a new role model for a generation growing up in conflict. In some areas, said Mais, where kids used to play “war” in the streets, they now play “civil defence” For Mais - who also works helping psychologically scarred children - the value of civil defenders as local role models was a key reason for her joining. “The kids are being mentally destroyed by this conflict. They need hope.”

With increasing female participation, the White Helmets are also working to challenge stereotypes and rigid structures. “Radical Islamist groups have tried to dissuade us from this work - they don’t want to see women joining,” said Shahd, a feisty Aleppan housewife who recently volunteered to join the White Helmets in her home city. “But we’re not going to let them dictate a narrow future for Syria. It’s important for us to visibly challenge this.” What is more, as Shahd added, the participation of women will also help dispel the image of women as “victims alone” - “we are strong, and we’re showing that to our communities, and to the world!”

And there is also pride to be had in the nature of the organisation itself. Constantly recruiting new volunteers, it has unified groups across the country around its principles of non-violence. Where regional teams are cut off from physical assistance, such as the branch currently besieged in the Damascus suburb of al-Qaboun (which recently responded to a mortar strike on a school that is reported to have killed 17 children), support is given in any way possible - such as through the recent awareness raising social media campaign. “Working with the White Helmets,” said Shahd, “it feels like you finally belong to something.”

“We want to be part of Syria’s reconstruction”

For a civilian population besieged by war, the “future” often seems increasingly unreachable. Plans for societal improvement are made laughable in an arena of destruction, calls for reform have turned to a scrabble for weapons, and dreams are buried under the grinding everyday quest for survival. But for the men and women of the civil defence, there is still hope to be found as they work to save lives and make life more liveable within communities. All four volunteers expressed their belief that their organisation would help to rebuild the country - both physically and in terms of providing a model for the Syrian values that have been obscured by war. “With both men and women taking part in rescues, we will change the way Syrians see themselves and their role in society,” said Shahd. “We want to be a part of Syria’s reconstruction. We will rebuild, and we will build, spreading values of equality, dignity and freedom. These are the true values of our revolution.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].