BOOK REVIEW: Curse of the Achille Lauro: A Tribute to Lost Souls

For many people, the words “Achille Lauro” - the name of the Italian cruise ship hijacked in 1985 by members of the Palestine Liberation Front (PLF) - connote a wickedness so pure that the suggestion of possible rational motivations for the affair is itself seen as a criminal offence.

According to the US - and Israeli-backed narrative, the hijacking incident - in which a 69-year-old disabled American Jew was killed and thrown overboard - was simply the latest manifestation of the Palestinians’ firm commitment to bloodthirsty terrorism.

While undeniably terrible, the murder of Leon Klinghoffer did not occur in a vacuum nor was it the intended goal of the botched PLF operation, which had been to engage Israeli troops when the ship reached Israel and to thus draw attention to the Palestinian cause.

It is in many ways thanks to the fanatically pro-Israel bent of the western media that events like these provoke a level of horror never elicited by Israeli behaviour, despite Israel’s far superior qualifications in the business of terrorism.

When the Israeli military fatally bulldozes elderly disabled Palestinians or young female American peace activists, for example, the atrocities are never deemed to be overly newsworthy - or cinema - and opera-worthy, for that matter.

Neither are regular episodes that involve mass Israeli slaughter of regional Arab populations and coordination of war crimes like the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre of up to several thousand Palestinian refugees in Beirut.

The very foundation of the state of Israel on Palestinian land - which entailed killing approximately 10,000 Palestinians, expulsing some 750,000 more, and destroying more than 530 villages - constitutes the initial crime after which crimes such as the killing of Klinghoffer become merely reactive in nature.

It is for these reasons that such accounts as Reem al-Nimer’s “Curse of the Achille Lauro: A Tribute to Lost Souls” come in handy, putting events in their proper historical context and humanising characters generally portrayed as inhuman.

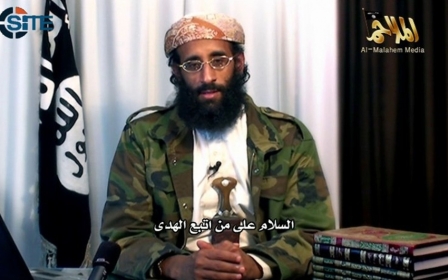

Nimer is the widow of Abu al-Abbas, the nom de guerre of Mohammad Abbas, master-mind of the Achille Lauro operation. Abbas was formerly the secretary-general of the PLF - one of the components of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) - as well as a member of the PLO’s executive committee. A strong believer in education, he held a degree in Arabic literature and worked as a schoolteacher prior to focusing his efforts solely on resistance.

As Nimer illustrates, Abbas’s upbringing in cold and squalid Palestinian refugee camps in Syria naturally helped shape his world view and elevate the liberation of Palestine to his utmost priority. The death of his mother - a result, he assumed, of unsanitary camp conditions - only exacerbated feelings of loss and dispossession; Nimer quotes him: “My mother was like my homeland. I never distinguished between the two. It is so difficult to lose a mother, and a homeland, and spend a lifetime looking for both.”

Hijacking logic

The Achille Lauro operation was carried out by four young men who had lost family and friends in none other than the Sabra and Shatila massacre, once again underscoring that whole notion of cause-and-effect that the Israelis prefer to ignore.

As Noam Chomsky outlines in a reflective essay in 2008, there was in fact a good bit of cause-and-effect at play in 1985. For starters, the hijacking was carried out in response to the previous week’s bombing of Tunis, where the PLO was then headquartered, in which the Israeli air force “killed 75 Tunisians and Palestinians with smart bombs that tore them to shreds, among other atrocities, as vividly reported from the scene by the prominent Israeli journalist Amnon Kapeliouk.”

The US lauded the bombing as an appropriate retaliation against “terrorist attacks,” which in this case referred to the murder of three Israelis in Cyprus by persons who, Chomsky points out, “Israel conceded… had nothing to do with Tunis.” But the perks of bombing Tunisia were obvious: “[M]ore exiled Palestinians could be killed there.”

And so on and so forth.

For his role in the Achille Lauro and other low-impact ventures, Abbas assumed a permanent position in Israeli and US crosshairs. Rendered a persona non grata in Tunisia on account of the hijacking affair, he and Nimer relocated to Iraq, where they lived for nearly two decades.

His militant resistance activities gradually dwindled, and Abbas dedicated himself to other fearsome hobbies such as tending to his vegetable garden with the family dog Rocky.

Despite having been officially pardoned under the Oslo Accords, Abbas was captured near Baghdad by the invading US army in April 2003 and advertised by CNN as “a convicted Palestinian terrorist.” The news outlet also quoted a statement from US Central Command: “The capture of Abu Abbas in Iraq removes a portion of the terror network supported by Iraq and represents yet another victory in the global war on terrorism.”

Again, forget that the number of humans terrorised by Abbas’s “network” is negligible when compared to the quantity of terror victims produced by his Israeli adversaries or his self-righteous captors - whose “war on terrorism” has essentially been a longwinded exercise in terror.

Abbas died suddenly in US custody at the age of 56 and was, as Nimer points out, one of four key Palestinians to perish within a short time span in 2004, including ex-PLO chairman Yasser Arafat. According to Nimer, there was no autopsy; according to the US, there was. Regardless, the war on terror bandwagon proved a profitable one for Israel.

The fantasy of nonviolence

Nimer, also Palestinian, was born in Nablus and moved to Beirut as a child. Unlike Abbas, she belonged to an elite family (in the book’s official press release, the publisher finds it necessary to specify that she was a “blue-eyed, blond-haired beauty”).

Following a period of dalliance with Alfa Romeo convertibles and the like, Nimer joined Arafat’s Fatah organisation before aligning herself with a series of more revolutionary groups and helping found a communist organisation.

As she describes it, this trajectory included military training in south Lebanon and bank-robbing to fund bombing operations. Twice married and the mother of three boys, Nimer witnessed eleven wars while living in various parts of the Arab world.

In his introduction to “Curse of the Achille Lauro,” Syrian historian Sami Moubayed claims that the book will chart the evolving mind-set of Nimer and her second husband Abbas: “Violence, she learned, is not the way. Violence is counter-productive.”

Never mind that many folks would presumably beg to differ with this analysis - such as residents of south Lebanon whose territory was liberated from brutal Israeli occupation purely by violent means.

Moubayed goes on to recall a comment Nimer once made to him in Beirut: “To move forward, Palestinians and Israelis alike must acknowledge our shortcomings. And then, without fear, we need to step into the future.”

Mercifully, the manuscript itself is not overly consumed by the grating banality and superficial why-can’t-we-all-just-get-along rhetoric that the introduction implies, although it is not without a reasonable dose of trite analysis; see, for example, her suggestion that it’s possible “to bring peace and stability to the Palestinian Territories” irrespective of the conflict with Israel.

It’s literally impossible, of course, to attain peace and stability in territories subjected to regular bombardment and other forms of harassment by a predatory neighbour that happens to be the preferred benefactor of the global superpower - and whose very existence is predicated on war.

It’s furthermore confounding that Nimer would argue for additional Palestinian concessions in the pursuit of coexistence with Israel, given her criticism of the Oslo Accords as a “non-solution” that left Palestine “fragmented” and overrun with Israeli settlements, and that generally complicated Palestinian life.

“Curse of the Achille Lauro” contains valuable historical details and biographical anecdotes (albeit not without some factual and mathematical errors). But one comes away from the book feeling hard-pressed to coalesce the insights offered into a coherent and substantive whole.

Forgiveness without peace?

Although he ultimately signed off on Oslo out of deference to Arafat, Abbas reacted to televised coverage of the accords, Nimer writes, by “pounding his head, almost in a hysteric trance, and suffer[ing] blood pressure problems that forced us to call in the doctors.”

Thanks to his “notoriety” as a military commander, Abbas’ endorsement of the agreement was “key to giving [it] traction and credibility among Palestinians” - thus implicating him, presumably, in the post-Oslo conversion of the Palestinian administration into de facto agents of Israeli oppression.

In a recent “Daily Star” article penned by Nimer in honour of the anniversary of Arafat’s death, she describes her book as “saying that all human life is precious, be it Palestinian or Israeli” - something it technically doesn’t say - and concludes: “I have forgiven the criminals, regardless of their identity. I did this for the sake of peace, and for the legacy of Arafat and Abu al-Abbas. So should others in the haunting Arab-Israeli conflict.”

A nice idea, perhaps, but one that might make more sense were Israeli crimes not ongoing.

- Belen Fernandez is the author of The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work, published by Verso. She is a contributing editor at Jacobin magazine.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].