Abortion in war time: How women break taboos in Yemen

TAIZ, Yemen - Elham ensures that her children prevent anyone from entering the room at her family home. Then, when the door is closed, she begins to speak quietly and nervously about why she had an abortion earlier this year.

At the age of 39, Elham - not her real name - already has five children, the youngest of whom is 18 months old. Her family, like millions of other Yemenis, have been left desitute by the two-year war, as many public sector employees go unpaid, including her husband, who has not received any salary for seven months.

My brain told me it was wrong to exhaust myself and make my husband suffer to provide a new baby with its needs

- Elham, mother

"My brain told me it was wrong to exhaust myself and make my husband suffer to provide a new baby with its needs," Elham says.

"We hardly have enough for our current children. If one of them is sick, we try our best to treat their sickness at home, as we cannot to pay for hospitals. The economic crisis does not allow us to have more children."

Elham explains that she took a contraceptive pill every day because they are cheap - but it was not enough. "The doctor told me that contraceptive pills are not safe for me, and I should use the loop," she says, using the local term for the intrauterine device.

During the first month of her pregnancy she unsuccessfully tried to locate supplies of the necessary abortion injection. "Finally, after three weeks, a relative of mine found it in Aden in February 2017 and sent it to me in Taiz."

The procedure, for which Elham had to sell some of her jewellery, finally took place during the second month of her pregnancy at a health facility in the city. Afterwards, she told anyone who asked that her life was at risk and that her doctor had recommended a termination.

"The loop is expensive, but in the end it cost me four times the price of the loop to abort," she reflects. When the interview is over, Elham arranges so that the MEE reporter can leave the house unseen.

High maternal mortality

Abortion is practically forbidden in Yemen, a taboo practice which takes place amid secrecy and which no one discusses. Usually it is only allowed early in the pregnancy if the mother's health is at risk, if there is a risk of congential defect or in cases of rape.

Only during the past decade have society and Islamic sheikhs started to accept abortion on these grounds. Women who terminate their pregnancy without what Yemeni culture regards as good reason are criticised.

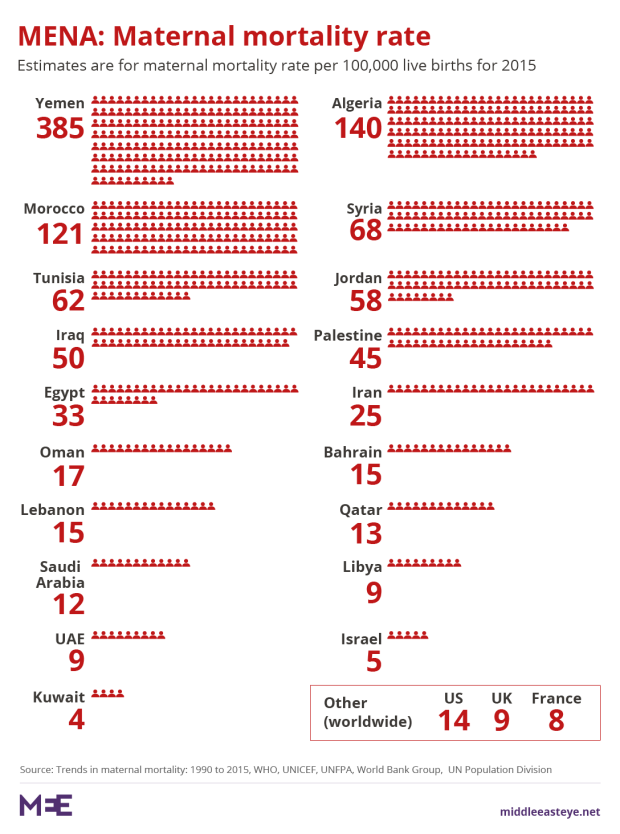

In peacetime, family planning in Taiz was difficult: health centres were scarce and many poorer families were unable to pay for medical prescriptions. The country also has the highest maternal mortality rate in the Middle East (see chart) and one of the higher total fertility rates in the region with an average of 3.77 births per woman.

But since April 2015, Taiz has been the scene of fierce fighting as Houthi rebels and fighters loyal to Saudi-backed President Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi have fought for control of Yemen’s third biggest city. Most of Taiz's hospitals and health facilities are now shut.

The situation is worse in rural areas, where 70 percent of the population live, where there is no medical contraception and where some mothers have more than 10 children.

Medical professionals report that more women now want abortions – but drugs and medical care are harder to find. The cheapest option, the contraceptive pill, now costs YR100 (40 cents) for 32 days, the the loop costs about $24 and an abortion, including the services of a medical professional, costs more than $80. The average wage in Yemen is about $50 per month.

'UNFPA advocates the right of all women to make their own decisions - free of coercion or violence - on when or how often to have children'

- Lankani Sikurajapathy, UNFPA in Yemen

In Elham’s case, the abortion injection eventually cost $48 – 50 percent higher than before the war. The procedure was carried out in a health facility by a trained abortionist – but even then, he refused to proceed until Elham's husband agreed.

The war in Taiz has increased the risks associated with pregnancy and childbirth for women, according to the UN Population Fund (UNFPA), which focuses on women's reproductive health.

"UNFPA advocates the right of all women to make their own decisions - free of coercion or violence - on when or how often to have children,” Lankani Sikurajapathy, the communication specialist for UNFPA in Yemen tells MEE.

In March 2016, there were an estimated 90,000 pregnant women in Taiz city alone, according to the UNFPA. Of those, 4,500 risked death in the next nine months due to complications from childbirth.

The role of religion

Aziza al-Azazi, a doctor of obstetrics and gynaecology based in Taiz city who is qualified to carry out abortions, says more women have come to her to ask for terminations since the war began.

Her first response to a patient in most circumstances is to advise them that their pregnancy is a blessing from Allah, that they should keep the baby. She explains that the hadiths – the collected sayings of the Prophet Mohammed - forbid abortion after 42 days, but that there is no such verse in the Quran.

"If the woman's life is at risk, then I ask to meet her husband to get agreement and then I abort pregnancy before 12 weeks,” she tells MEE. She will not abort after 12 weeks, even if the woman's health is at risk, unless there is a fatwa from a religious sheikh.

Usually she advises women that prevention is better than cure - but often finds they do not follow her advice.

"The women have to follow the instructions of doctors to prevent any future suffering,” she says, "but many of them are not educated enough. They decide not to use loops and other safe methods, and then find themselves in trouble."

Some medical professionals terminate abortions for other reasons – as happened with Elham - and then claim the woman’s health is at risk to avoid punishment, usually a fine or imprisonment of up to 10 years.

'Prevent real pain for other women'

Abeer Abdulmajeed, 28, married five years ago and wanted a baby: her family is well-off and her husband is a Saudi immigrant. But when she became pregnant, her doctor advised her that the foetus would not be able to develop and that she should end the pregnancy.

Clerics told Abdulmajeed that she could end her pregnancy before 42 days, which she did.

"I left Taiz for Sanaa in June 2016 to end my pregnancy because I could not find the abortion injection in Taiz,” she says. "I was sad to end my first pregnancy.”

The journey itself was difficult and dangerous, taking more than 12 hours to travel 250km across war-torn Yemen. "Now I am taking precautions for the next pregnancy, as my husband and I hope to have a baby."

'If every women could end her pregnancy, then this would help spread adultery. Society has to reject women who end pregnancy after 42 days for any reason because they disobey Islam'

- Ahmed al-Fioush, religious sheikh

Ahmed al-Fioush, the religious sheikh in Taiz province, told MEE that abortion is forbidden in Islam, but that some religious scholars advise women that they can end their pregnancy before 42 days if their life is at risk and this is the only reason for abortion.

"There is no clear verse in the Quran which forbids abortion,” he explains, "but there are several hadiths forbidding abortion. It is like killing a soul.

"If every woman could end her pregnancy, then this would help spread adultery. Society has to reject women who end pregnancy after 42 days for any reason because they disobey Islam."

For her part, Elham says that she has not defied the Quran - only the hadiths forbid it, she explains - and wanted to tell her story so that other women could learn from the experience.

"The only reason that led me to pregnancy was using contraceptive pills, so I advise women to use the loop, which is safer than pills,” she says. "This will prevent them putting themselves through real pain."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].