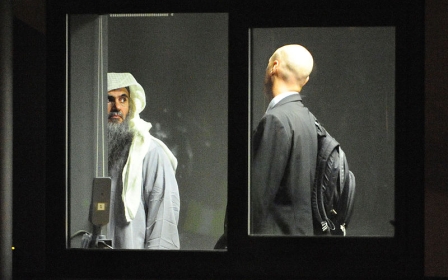

Abu Qatada acquittal raises questions about his next move

High-profile Muslim cleric Abu Qatada has been found not guilty of planning a terrorism attack on an American school in the late 1990s, raising questions about why he was acquitted – and what he might do next.

Qatada, extradited from Britain last July after a lengthy and expensive battle to remain in the country, is today in a Jordanian jail awaiting a decision on a further terrorism charge – a plot to bomb tourists at millennium celebrations in 2000. The case has been adjourned until 7 September. If he is acquitted then, he will walk free.

After the verdict, many people inside and outside Jordan expect Qatada, whose real name is Omar Mahmoud Mohammed Othman, will be found not guilty.

But the Jordan he may re-join as a free man is a markedly different place than the one he fled in 1993. Straining to cope with a civil war to its north in Syria and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant-led sectarian disorder to its east in Iraq, it’s a country looking for backstops against the increasingly bloody chaos that is threatening to destabilise the region – and in Abu Qatada, a man it once sentenced to death, Jordan may have an unlikely ally in its fight to keep ISIL at bay.

Qatada is the Salafi leader in Jordan, and his reputation for radicalism stems from sermons and writings dating from 1999 where he advocated attacking Americans, endorsed the killing of Jews, framed the 9/11 attacks as a battle between Islam and Christendom, and praised Osama Bin Laden. Qatada was once described as a senior figure in al-Qaeda – the terrorist group that disavowed ISIL for being too extreme.

The charges against Qatada relate not to these comments and this terrorist connection but to specific acts of terrorism. They also hinge on controversial evidence – a co-defendant’s testimony – reportedly obtained through torture. Fifty-four year old Qatada has denied all charges against him.

Evidence allegedly obtained through torture used in court

Qatada’s current trial is a retrial, featuring the same evidence that resulted in convictions in absentia in 1999 and 2000. At that time, Qatada was in the United Kingdom, where he had been granted asylum on the grounds of religious persecution: he claimed he had been tortured in Jordan.

An eight-year battle to avoid extradition to Jordan – reportedly costing the UK taxpayer £1.7m – resulted in a diplomatic agreement between Britain and Jordan to send Qatada back to Jordan, on condition that evidence believed to have been obtained through torture could not be used in court. (In Jordan, this is not a new concept: the country’s constitution prohibits the use of evidence obtained through torture.)

Despite this, the court ruled the testimony was admissible as evidence – and then found Qatada not guilty. Judges said the court had found insufficient evidence to convict the cleric, despite sentencing him to death with the same evidence 14 years ago.

Qatada’s lawyer, Ghazi al-Thneibet, told Middle East Eye that Qatada was “very happy” about Thursday's decision, calling it a “first step” and saying he was looking forward to a final decision.

Al-Thneibet said he was pleased with how the trial had proceeded, despite the court’s decision to include evidence that may have been obtained through torture. But he was clear that is client wasn’t celebrating just yet: “This decision is nothing if he is condemned in September.”

For human rights advocates, the admissibility of this evidence is a pressing issue.

“In spite of this verdict, there is still a concern that diplomatic assurances are not reliable, given that the court included a confession allegedly obtained through torture,” said Human Rights Watch Jordan researcher Adam Coogle, who attended much of the trial.

Article 3 of the treaty between the UK and Jordan, dated 24 March 2013, puts the onus on the prosecution to make clear “to a high standard that such statement has been provided out of free-will and choice and was not obtained by torture or ill treatment by the authorities of the receiving State.”

From Coogle’s perspective, the evidence should not have been admitted. That Qatada was acquitted despite its inclusion makes the matter all the more puzzling.

Timing, geopolitics may clarify acquittal

The timing of the case and regional geopolitics may offer an explanation.

ISIL’s emergence as a ferocious, border-eviscerating Islamic force has Jordan worried. Jordan has been sending reinforcements – manpower and armour – to its borders with Syria and Iraq, but on the Iraqi border especially, the situation remains tense. Mohammed al-Momani, Jordan’s minister of information, this week described the situation in Iraq as “non-normal”, telling Middle East Eye that “border traffic is at its lowest point right now due to the security situation”.

In ISIL, Jordan and Abu Qatada share an enemy. A source who regularly attended Qatada’s trial said the cleric used to address the press from his cage in the courtroom, criticising ISIL and declaring his support for its rival Jabhat al-Nusra.

Qatada’s lawyers put a stop to this by requesting journalists and the public only be permitted into the courtroom once the judge had arrived, effectively closing their client’s window for sermonising, but the message was out there: Jordan’s top Salafi backs Nusra, not ISIL.

This courtroom source thinks the Jordanian government may have seen an opportunity here: “It makes sense that Qatada, the Salafi leader in Jordan, is being acquitted in order to play a positive role in steering the youth of Jordan away from ISIL.”

Ayman Khalil, the director of the Director of the Arab Institute for Security Studies at the University of Jordan, disagreed that politics had come before justice.

“I believe the Jordanian sentence took into account the specifics of the case in a logical and neutral manner,” he said. “This sentence was not politically influenced.”

But within this logic and neutrality, Khalil sees something he describes as “a new approach on the regional level”. He said: “While Islamists, specifically Muslim Brotherhood operatives in Egypt are being prosecuted and sentenced to death, the Jordanian legal system views this differently and believes that this trial needs not to be politically biased.”

“The Jordanian sentence may bring about the ingredients of a truce with radical Islamic elements – and possibly an avenue for dialogue. The long term treatment for radicalism in the region should rely on sponsoring dialogue and improving confidence.”

If Qatada is to have a role in any dialogue, it is likely to be from within Jordan: almost as soon as the acquittal was announced, Downing Street confirmed that Abu Qatada would not be permitted to re-enter the UK, “end of story”.

Lawyer al-Thneibnet declined to comment on his client’s intentions to return to the UK or his plans for life after the trial. For now, there is the 7 September ruling to focus on, and, presumably, a post-prison plan to develop.

Regardless of where Qatada bases himself, he is a well-known figure with followers in the Middle East, the United Kingdom and beyond. How he will reconnect with them and to what end remain to be seen – but in Jordan, more than a few experts are confident Qatada’s life and work will begin anew in September.

In the meanwhile, al-Thneibnet is working on an application for bail. Although Jordanian courts typically do not grant bail on terrorism cases, the lawyer thinks it is worth a try.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].