Algeria's new constitution: The illusion of transparency

ALGIERS – “There is no dismantlement of the presidential citadel,” analyst Fatiha Benabbou said of the new Algerian constitution. “It will remain an impregnable fortress.”

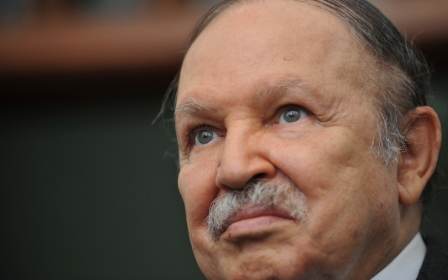

The draft of the new constitution was presented on 5 January by Ahmed Ouyahia, Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s chief of staff, with the parliament due to vote on it in February.

“Unlike Tunisia or Morocco, which reviewed their fundamental texts [constitutions] in order to give more liberties, in Algeria, the president hangs onto his prerogatives,” constitution expert Benabbou told Middle East Eye.

However, on paper, some concessions are visible. For example, the president can now legislate on urgent issues by issuing presidential edicts after a recommendation from the Council of State, a judicial body above the administrative court that is supposed to regulate it.

Also, instead of being granted four months to legislate during the parliamentary holidays, the head of state has now only two months. In addition to that, the constitutional council has been given a new prerogative to guarantee the rights and liberties enshrined by the constitution. Also, the notion of security of tenure of the constitutional council judges has been introduced.

“But in practice, it is not that simple,” said Benabbou.

“In Algeria, the state council is not the supreme institution that it should be. Recently, a judgement by the state council was disavowed by the administrative court, which has inferior jurisdiction. Besides, the president makes the nominations for the members of the constitutional council, so they remain highly political.”

A ‘milestone in human history’

In this context (where things in real life look very different than they do on paper) the progress hailed by a part of the political class and civil society – such as the constitution’s mentions of a return to the limitation of two presidential mandates, the abolition of prison sentences for press offenses, and the possibility for the opposition to pass the laws which have been adopted before the constitutional council – look much smaller.

The one key achievement, however, has been the formalisation of the Tamazight (Berber) language as a national language alongside Arabic has been unanimously praised.

For Ali Brahimi, an activist and the founder of the Berber Cultural Movement, “a milestone has been reached in the scale of human history.”

After centuries of tensions, Brahimi says the move marks “the end of a mythology - that of an Arab Algeria” that has tried to force a unified identity on its population,

“The North African people are the only ones who have been asked to be Arab because they are Muslim,” he told MEE.

But Brahimi still remains clear-headed about the difficulties yet to come.

“I know very well that it requires resources which will continue to be dominated by the state, but it is up to the cultural and political activists of the Berber cause to discuss things together in order to launch a new seminar of the Berber Cultural Movement, as well as a new political force based on the identity, which will compel the state to fulfil its commitments.”

The legal opposition in Algeria has also asked the state for clarifications and for assurances that the new changes will be enacted.

“Regarding the protection of the first right of the citizen - that is to say the guarantee of having his electoral choice recognised and respected - the message needs clarification and the greatest attention,” the RCD (Rassemblement pour la culture et la démocratie, an opposition party) said in a statement.

“The announcement of the constitutionalisation of an elections monitoring commission appears to be a window-dressing offer meant to feed confusion in order to perpetuate the methods of the past, and this does not answer either the crucial issue of the legitimacy of the institutions or, as a result, the demand of the opposition.”

Vote scheduled for mid-February

Abderrezak Makri, of the MSP party (an Islamist opposition party) said he regrets that “this constitution, which is neither consensual nor having the potential for great reforms, expresses only the views of the president and his entourage”. Makri is also dissatisfied that “the proposition of the political class regarding the establishment of the independent national authority for the organisation of elections” has not been taken into account.

On that point, the president’s chief of staff has stressed that the draft takes into consideration 70 percent of the proposals expressed by the participants of the consultations on the matter carried out since 2011.

But Makri said: “Nothing will change as long as the Ministry of the Interior is in charge of the file of elections. The laws have never been a problem in Algeria; sometimes the laws are perfect. The problems are the corruption of the political system and the non-respect and non-implementation of the laws.”

Aissa Kassi, speaker of the dissident wing of the governing National Liberation Front (FLN) which opposed to general secretary Amar Saadani, provides a more nuanced comment: “This text [the constitution], which integrates some proposals made by the FLN in 2006, includes real steps forward. But between the hype (we were told about a Second Republic, a new state) the draft and the reality, there is a whole world,” he said, adding that he remains “optimistic but with reservations”.

“The regime will remain a very presidential one. Let’s say that this project is part of a process of reforms widening and, as such, is perfectible. But to achieve that aim, real and active political forces, not just marginal actors, will be necessary,” he said.

This article was originally published on Middle East Eye's French page.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].